Tips for the Pre-Successful: Examining the Good Place

(Spoiler Warnings for the first season of The Good Place)

Edgar and I recently watched Season 3 of The Good Place on Netflix – we don’t have a digital box to watch network television and our schedules tend to be fairly full, so we can’t watch it as it comes out. I’m a big fan of the show – I happen to think that it has some of the best writing and performance in television, and we’re supposedly in a golden age of prestige television. So, as I do when I enjoy something, I try to dive into the creative process.

Reportedly, on the first day the writers’ room of The Good Place got together, I’m given to understand that creator Michael Schur put the following questions up on a white board:

Is it funny?

Are the characters being developed?

Does the episode ask and answer a question about ethics?

Is it compelling?

Is it consistent with the long game?

Are we making use of the premise that the show is set in the afterlife?

These six questions form what I call a paradigm: a basic set of instructions or ideas for coming up with the foundation of a story. It starts with the tone, affirms a focus on character over plot (though, of course, later on it affirms the presence of an overarching plot,) and checks quality and perspective later on.

The third question – “Does the episode ask and answer a question about ethics” – is of special interest to me. The Good Place has a definite focus, and is definitely a vehicle to learn about big ideas in ethics, ranging from a thought experiment as basic as The Trolley Problem to an open-ended question as fundamentally important as “what do we owe each other?”

David Foster Wallace predicted that the rebels of the future would be those who would risk a yawn instead of a gasp — predicting a kind of post-ironic puritanism. This prediction has come true, as little as I want to admit Foster Wallace was correct about things — for just such puritanical reasons, admittedly.

I think that the show’s handling of this is very important for an aspiring writer or creator to notice. I recently saw a blog post on Tumblr that explored the parallel development between Christian Fiction (which the author noted as generally being less compelling, due to its ideological baggage and the duty that writers of such fiction feel to put forward a particular moral message) and contemporary fan fiction (which I feel is very important, as fan fiction is often the proving ground for aspiring writers before they make the jump to original fiction – though the question of whether that is necessarily worthwhile will have to wait for another day.) Namely, the fact that a lot of contemporary fan fiction feels the need to put forward an image of purity and stick by it, avoiding making any of the heroes “problematic” and keeping the villains from going off the deep end.

The model put forward by The Good Place would be a good one for many of these writers to copy: put desired tone and focus – humor and character, in the case of the sitcom – ahead of concerns about the desired qualities, and focus more on exploring that space than describing it. It seems fairly clear to me that the creators of The Good Place have some extensive thoughts on what constitutes good and bad ethics: but they are allowing that perspective to grow and evolve as they move through the fictional space that they are working in.

And that isn’t the last step. After these questions have been answered, there’s also the quality check (is it compelling?), the plot check (is it consistent with the long game?) and the premise check (Are we making use of the premise that the show is set in the afterlife?) By placing the thematic question in the middle, they are giving it a place of importance, but they’re not allowing it to have overriding control over their story. It’s a factor, not the factor.

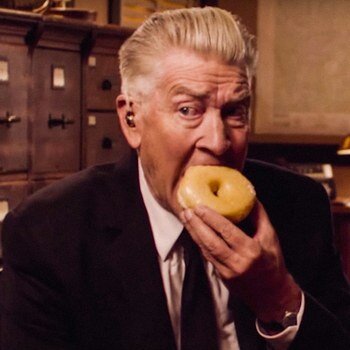

Focus is important, too: just look at what happened when David Lynch stopped paying attention to Season 2 of Twin Peaks — there was an entire “cross-dressing yellow-face” plot line that people avoid mentioning and someone ended up being trapped in a doorknob.

I think this is part of why the show works: there is a consistency in tone and quality that is missing from many other shows – even the highest quality prestige television (Game of Thrones, I’m looking at you,) seems to me to be of lower quality than The Good Place because it isn’t kept as consistent.

Of course, the final question brings to mind the fact that (for me at least,) the show would have been fascinating even without the twist at the end of Season 1. Consider the basic premise: a woman wakes up in heaven, and knows for a fact that she should not be there because of her behavior on Earth. In such a situation, what can someone do?

And here’s another lesson that creatives can learn from: a twist works much better when your starting premise is interesting and the twist is a logical outgrowth of that premise. Many writers set out to put a twist on a tired old premise, but they don’t take the time to buttress it and make the tired premise work in the first place.

The Star Trek quote is from the episode that cemented the preferred facial hair for all evil doppelgangers in the zeitgeist. Don’t act like it doesn’t have a cultural impact.

In The Good Place, the main character Eleanor wakes up in The Good Place (essentially heaven) and is told that she is one of the vanishingly small percentage of people who made it in. Except she knows for a fact that she isn’t, and she has to pose as a much better person to fit in (I’m reminded of a quote from Star Trek, from the original series episode “Mirror, Mirror”: “It was far easier for you, as civilized men, to behave like barbarians than it was for them, as barbarians, to behave like civilized men.”)

Eleanor struggles with the help of her supposed soul mate, Chidi Anagonye – a Nigerian-born Professor of Moral Philosophy – to become a better person in the hopes that she could argue that she has made the cut to deserve her position in the Good Place.

Smash cut to the end of Season 1, where Eleanor declares confidently, in front of Michael, the architect of the slice of heaven they’ve been living in, and in front of her friends, that “we’re in the bad place.” and Ted Danson’s demeanor just changes, and he lets out the most devilish giggle. The writers set up the idea that something is wrong here from the first episode, and played out the idea that this mistake in the constitution of this tiny universe led to nothing but suffering for the people in it: a new kind of hell, where the damned torture each other (and here, we have Jean-Paul Sartre’s “hell is other people” writ large and proved over six and a half hours.)

It’s something that the viewer would have been thinking at the back of their mind for weeks, if they were watching this in real time. I must admit, I was somewhat disappointed with the idea that they shrank back from the compelling, if difficult, premise of a problem in what is essentially heaven, but I understand: sometimes the execution of a high concept is difficult to pull off, and aiming for a more traditional end is preferable to floundering as you pursue the more complicated one (though, of course, this is what “the long game” mentioned in the questions was from the beginning.)

Another thing I appreciate about the show is the limited scope: this fourth season is – I understand – going to be the last. In recent years, the tendency towards more limited series has struck me as an improvement over the old days of constantly-extending seasons. Of course, the appearance of an end is an illusion: there is no cancellation in television, only apparent cancellation and the network or any given streaming service might decide to resuscitate its corpse to shamble through another season (much as Josef K. in The Trial can only hope for apparent acquittal, and may be dragged back at any time for a re-trial. The difference between the two options — indefinite postponement and apparent acquittal being the major point of definition between Control and Discipline, respectively.)

this show went on for nine seasons and all it did was convince a bunch of dudes that wearing a suit was a personality.

I view the movement towards a limited story, with definable boundaries in time to either side, as a major improvement. It’s one of the few ways to actually get a satisfying ending out of television, because it allows you to aim at a particular ending: when How I Met Your Mother tried to do the same thing (aiming for a particular ending, that is,) it led to an uproar. That show tried the other option from The Trial: it indefinitely postponed the reveal that was at the heart of the show, and in the end, after so much postponement, there was no possible satisfying reveal.

An aside, a caveat, an exception: It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia doesn’t follow this, but literally nothing about that show makes sense from an analytic standpoint, and a lot of critics are scrambling to fix the gap in their understanding. There is a lot to be said about this show, and we’ll probably write about it in the future — but this isn’t a television review blog, so it’ll have to wait. Put it on Indefinite Postponement.

Seen here in a press photo (I believe) parodying the appearance of The Good Place promotional images. Just about nothing holds true for this show.

So I suppose the upshot of all of this is that there are creative lessons that can be drawn from television – much to the post-mortem chagrin of George Trow, one of the intellectual luminaries we look to from time to time, – which are especially useful for people who are involved in making serialized works (which is just about every creative thing on the internet.)

First, the use of a checklist, like that put forward by The Good Place can allow you to do a “vibe check” on your own work, and make sure that everything hangs together and connects into what you’re trying to achieve. It may be more productive than outlining, because it could allow you to tap into some of the spontaneity that is normally lost in the process of structuring the whole work before you begin it.

Second, grounding your twist (should you decide to use one – there isn’t really a Shyamalan-esque twist in The Lord of the Rings, and it didn’t really need it) in the reality you establish from the initial moment of your work is essential to using the device. Moreover, you need to make sure that the story, before the twist, is actually interesting. You may risk disappointing some people by not pursuing the original premise, but they can write their own.

Finally, keeping the scope controlled and tightly focused is essential. This is something I struggle with a lot: resist the urge to sprawl over the whole of the available fictional space. Pick a starting point and an ending point, and fill in as much of the intervening space as you have to, but avoid going beyond the boundaries you have set as much as you can. Your work will be better for it.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)