Edgar's Book Round-Up, January-March 2019

I haven’t been reading as much this year, or at least not as many books. I think I’m still reading with the same frequency, but this year I decided to dial back my Goodreads challenge number, because I wanted to read some denser, odder stuff. I found that in trying to read many books (last year I hit 45, which I think is pretty good considering I periodically do other stuff), I was privileging briefer ones. That’s no bad thing — efficient style is nothing to be sneezed at, and frankly I think we should all be reading more poetry — but I had been eyeballing a few longer and more intense pieces for quite some time.

Which is why I started off with Satantango, Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s best-known work. It is better known in part because of Bela Tarr’s incredibly long film adaptation, which I have not seen, though having read the novel I’m curious how successful it could be.

Satantango itself sounds like it should be a tough read: twelve chapters of varying length, each of which is one long paragraph. The plot follows, from several viewpoints, the dissolution of a nameless town populated by drunken assholes, layabouts, and way too many spiders (maybe), as they await and then are lead to, they hope, some kind of salvation by Irimias and Petrina, who are themselves hiding a great deal.

But honestly, if you’re reading it for the plot, you’re missing the point. I cannot read Hungarian, but Satantango makes me wish I did (though George Szirtes’ translation is, as far as I can tell, a lovely rendition of the work). Krasznahorkai’s style — or at least Szirtes’ translation — hews pretty closely to a modernist affect: dense and enveloping, the paragraphs and sentences unroll like weather across an open plain. They’re magnetic and desperate in a way that I have rarely encountered — as if the style, the conceit, is a grasp for some semblance of control in a world that is falling apart. The fact that the novel slides into a hallucinatory kind of fantasy only makes that sense of desperation more heightened, the urgency of the characters’ Beckettian scheming and chicanery more imminently present to the story. It was a hell of a way to start off the year.

Photograph from Jacobin.

Next up was Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, a scathing analysis of the shape of the problem (the problem being late-capitalist society). I was already on board for Fisher, having read Ghosts of My Life last year; his ability to fuse pop-cultural touchstones with a strong background in philosophy and, you know, logic and stuff, makes for magnetic reading. And much like another writer with similar capabilities — I’m talking about Thomas Ligotti’s Conspiracy Against the Human Race — the outlook is grim.

In not very many pages, Fisher outlines the shape of capitalist realism: capitalism as it stands makes it impossible to imagine not-capitalism, and this is how we will be destroyed. Drawing on a broad array of cultural touchstones and his own experiences as an instructor, as well as, of course, other writers of theory, Capitalist Realism sketches a society that is committed to eating itself — a sketch he filled in with Ghosts of My Life and, later, The Weird and the Eerie, which I have not yet read — with the kind of clarity that comes from helplessly watching the sun come up from the wrong side.

It’s scarcely surprising that Fisher could summon that kind of intensity, given the kind of batshit shenanigans he helped pull in his time in the ccru. But while the other most notable member of the ccru, Nick Land, got himself into an amphetamine-fueled personality crisis, Fisher maybe stared down the yawning mouth of the beast a little too long. His unfortunate death in 2017 means that we will never see the solutions he hinted at in his works, and which would have, supposedly, been illustrated in a project entitled Acid Communism. Presumably, the best we can do now is try to imagine something beyond, something outside of, the machine that means I’ll be waking up, at maximum six hours after I finish writing this piece and hopefully pass out immediately, to go to work.

So that was all a bit grim. I needed a breather, something a little more lively — so I treated myself to the fourth and final installment of a series that has haunted me for half of my life, Carlos Ruiz Zafon’s Cemetery of Forgotten Books cycle. The latest, and last, is The Labyrinth of the Spirits, which was a departure from prior installments in a number of ways, most noticeably in that the action departed from Barcelona for substantial portions of the novel (but just to Madrid), and the main character was a woman: the mysterious, hypercompetent Alicia Gris. Her search for, initially, Mauricio Valls, the vanished, fictional minister of culture under Franco, leads her into a characteristically gripping and meltingly gorgeous gothic chase, through the shattered streets of Barcelona and, of course, the twisting passageways of the Cemetery of Forgotten Books itself. Honestly, to adequately proclaim how much I love this series would be an entire post by itself, so I will simply encourage the reader to snag one wherever they may find it.

After that, I embarked on Anti-Oedipus, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s sprawling work of, Foucault argued, ethics. It’s worth noting that, at work, I leave my current reading on a little shelf in the locker room, along with other people’s stuff and, for some reason, recent issues of Women’s Health that keep appearing there; Anti-Oedipus took so long that my coworkers started giving me a hard time about it, and telling me to read something more interesting.

I’d argue about whether or not it’s interesting, but I nonetheless took a break in the middle of Anti-Oedipus to read M. L. Rio’s delightful academic thriller, If We Were Villains. It was exactly the break I needed: the shenanigans of a bunch of Shakespeare-addled theatre students, one of whom winds up dead (of course) was a perfect breather for me. Smart and fun, it was kind of a keyboard-smash of stuff I was going to like anyway, especially given my affection for things like Slings and Arrows, The Play’s the Thing, and Kansas City’s Shakespeare in the Park, which first taught me to love A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Then I finished Anti-Oedipus. All I will say is that I am not the person to discuss it at much length, if only because of my personal practice of reading philosophy as almost anything else — in this case, ultimately, as poetry. It worked well.

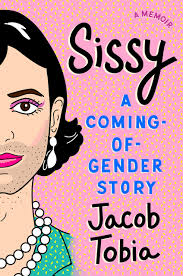

Which brings us to the book I finished most recently, Jacob Tobia’s Sissy: a Coming-of-Gender Story. I have long been a casual fan of Tobia’s; their work was some of the first that I read when I was examining my own gender, and their articles have always been characterized, for me, with an emphasis on the joys of gender nonconforming life, rather than on its struggles. I actually preordered Sissy, and was delighted when it came. After clearing my docket (see above), I dove into it eagerly, and was not at all disappointed.

As the subtitle suggests, the book chronicles Tobia’s arrival at a nonbinary gender, from the early days of playing with Grandma’s jewelry to their post-college attempts to find work. Tobia is fairly aware of the relatively charmed nature of their life: a full ride to Duke and an invitation to the Obama-era White House both feature in the story. They don’t linger too long on the travails of coming to an understanding of oneself as trans, and they also don’t bog the reader down in the linguistic niceties of the LGBTQ+ community (which isn’t bad, necessarily, but that’s not the kind of book this is). Their narrative of struggle with, and love for, their church adds a great deal of depth to their experience and, by extension, the book as a whole: regardless of how one feels about organized religion, it’s a sad fact that narratives of queer peoples’ religious experiences are often either solely negative, or else pushed aside, and Tobia approaches their own spiritual background with clarity and surprising gentleness.

With a crisp and generally upbeat tone, not dissimilar to their prior publications, they describe their journey to a fuller understanding of self, and the many ways that understanding grew and, ultimately, flourished in their life. While the occasional reliance on internet-standard punctuation and typesetting conventions occasionally grated on me (precious little ever really needs to be set in all caps, for example), I would not — and have not, because I can be deeply obnoxious — hesitate to recommend it to anyone searching for a different view on the trans experience.

Now I am working my way through a book I casually sought after for years and finally found while on an unrelated mission to a used-books store. It’s… okay. But, alas, after all those years of searching — it’s just okay.