The Minotaur in the Labyrinthine Office: on Bureaucracy (Fisher's Ghosts, part 1)

I’ve already read this book twice this year — it’s an excellent example of polemic.

I was originally going to write on this for the ten year anniversary of Mark Fisher’s seminal Capitalist Realism, but events unfolded differently than expected.

So it’s going to be a series. Welcome to Part 1 of this anniversary series on Capitalist Realism. I’m calling it “Fisher’s Ghosts.”

Edgar and I moved at the beginning of September, and we’re now reaching the 60-day mark after that. All around the same time, we’ve both been working to put through an income-driven repayment plan for my student loans, our cooking gas was turned off, we received a $160 bill from our former internet provider and we are approaching a deadline on clearing out a storage unit some 50 miles distant from our house.

As such, we have been interacting with a lot of bureaucracy, and suffering the slings and arrows of doing so on the back foot. I’ve got a lot of experience navigating bureaucracies, and I can only imagine the strain that it puts people without my history in the university under. I am reminded of a passage from Capitalist Realism, because I recently reread it in anticipation of doing the aforementioned anniversary piece. On page twenty of the book, he writes:

With the triumph of neoliberalism, bureaucracy was supposed to have been made obsolete; a relic of an unlamented Stalinist past. Yet this is at odds with the experiences of most people working and living in late capitalism, for whom bureaucracy remains very much a part of everyday life. Instead of disappearing, bureaucracy has changed its form; and this new, decentralized form has allowed it to proliferate.

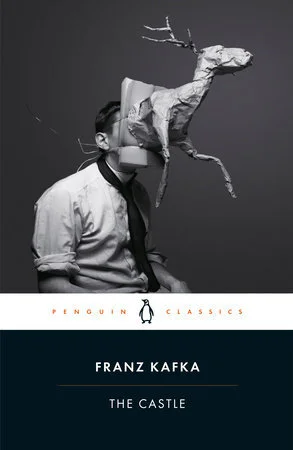

I was going to use a different cover of this book as a reference to the “vast decentralized bureaucracy” — but this Canadian cover captured an emotion I have experienced but for which I had no words.

Say what you will of the Soviet Union – and there are many, many negative things to say about the Soviet Union (sorry, Tankies, we may be anti-capitalist but we have issues) – but there wasn’t a single phone-tree in the damn thing. You have to pass through a gauntlet of insentient robotic voices to reach a person who may or may not be able to help you, and has probably been trained as a salesman instead of a customer service representative.

The worst company out of this whole lot is Comcast – who doesn’t actually have a separate customer service division, and just has several different sales divisions, working to recapture fleeing revenue. I had experience with them when I was at graduate school in New Mexico, and they provided my television service. I only escaped when I moved to a region they didn’t operate and they could no longer make an argument for my continued buy-in of their service, because they – like all other large corporations – are aspects of the Society of Control they operate on a principle of indefinite deferment – oh but you’ll want this, surely you want this, you can’t possibly want to cancel, we know your desires, we offer the only means to fulfill them.

And, likewise, as an educator, I worked in one of the largest bureaucratic formations in America – the university system. For two weeks at the start of every semester I had to enter enrollment information, by hand, into an aging computer system; every few years I was brought up for observation, which required juggling my schedule and that of one of my colleagues; there were optional-in-name-only meetings and events. The university socializes the middle class into bureaucratic behavior, and teaches them to fear it, and as a teacher, it is my job to be the agent of that socialization.

White Sea Canal agitprop — the text reads “Canal Army soldier! The heat of your work will melt your prison term!”

The whole function of bureaucracy is to increase efficiency, but it is efficiency in a pseudo-Stalinist manipulation of Signs and Symbols, not of actually-existing things. An argument can be made for this – dollars are measurable, happiness is not; subscribers are measurable, misery is not. If you can get a dozen immiserated people resigned to paying you a monthly fee for a nominal service for the outlay it takes to get four happy people who actually want your service, and will pay that same monthly fee, then you’re going to have to occasionally deal with up to a dozen miserable people – but it is a bad argument. I’m not about to argue that the things that are measurable are unimportant – you can certainly count the drop in the number of deaths from Polio after vaccination was introduced – but you can’t argue that only measurable things are important. On page 43 of Capitalist Realism, Fisher references Stalin’s White Sea Canal Project of 1931-33, whereby an effort was made to turn a massive engineering project into a successful public relations spectacle (interestingly – when it’s a government it’s propaganda; when it’s a corporation it’s public relations. There is no difference between the two things.) Fisher summarizes the tendency with a simple maxim: “In a process that repeats itself with iron predictability everywhere that they are installed, targets quickly cease to be a way of measuring performance and become ends in themselves.” (underlining is mine) That is, if you’re measuring success by a metric, raising the metric becomes your goal, not success. That’s the seductive quality of metrics: they allow you to experience the “bureaucratic pleasure of watching numbers get bigger” and convincing yourself that you’re doing good.

Of course, there is one thing that I feel that Fisher missed, as someone who was critiquing bureaucracy from the inside. Bureaucracy, especially in its contemporary, neoliberal formation (what I tend to think of as “exterminism”), operates on a more sophisticated iteration of the logic of the Nuremberg Defense. The adjustor denies your claim because they’ve been given criteria to follow: they don’t have a choice, they’ve been given their standard. The people who wrote the criteria that led to your claim being denied aren’t responsible: they don’t have a choice, they’re looking at the big picture. The board of the insurance company can’t do anything to help you: they don’t know about your particular situation, they only manage the business side of things, and that only occasionally. The man who pulled the trigger didn’t choose to do it; the man who ordered the trigger pulled didn’t pull it himself. No one is responsible.

Surrealist filmmaker Terry Gilliam knows this all intimately — as can be seen from Brazil.

That’s the real secret: Responsibility is the Minotaur — or Basilisk — at the center of the Labyrinth of Bureaucracy. It is the thing that the Labyrinth was constructed to defer and obscure and contain.

The real issue here is that we could easily construct an alternative system based on the same foundation that would achieve constructive ends. We have done that in the past. Think of the Apollo Program: the United States put twelve astronauts on the moon, a satellite of our planet that is 239,000 miles away, a place so distant that it takes a second and a half for a radio signal from Earth to reach it. We did this with computers roughly as powerful as an Apple II.

Margaret Hamilton, standing next to the software code she wrote for the Apollo Program: the manipulation of signs and symbols given a productive end, and so elevated above mere bureaucracy.

We accomplished this task using bureaucratic tools. All of the best minds were brought together, given this goal, and told to get to work, and it did work. We accomplished things no one else did, and we did it using tools that are now being used to extract revenue from working-class people. So perhaps the problem isn’t bureaucracy – but the mental framework that surrounds it. Once again, I regret to inform you, the problem is Capitalism. I know, shocking that I might make that assertion.

Really Existing Socialism had many, many problems, but a fair number of the capitalist critiques of Soviet inefficiency are based in the same factors that make contemporary bureaucracy so terrible. If you measure efficiency in dollars, not actual results, then a non-profit-seeking effort is – by definition! – inefficient. If you achieve your target numbers, who cares if you achieved your stated goal? Really Existing Capitalism reproduces the Stalinist tendency towards the manipulation of apparent signs instead of producing an end result, as well as the over-quantification that is often put forward as the problem with bureaucracy: it just does this in the service of extracting profit from people, and since the immiseration of customers doesn’t interfere with the extraction of profit, there’s no real reason to reduce the amount of alienation and misery that comes out of it.

And it’s not simply the customers who suffer – I’ve known multiple call center employees who loathed the work. (Note: it’s not like any of them dreamed of working in a call center, as frustrating as dealing with them is, you have to have sympathy with them.) One of them, a former roommate, hated the job so much that he was misdiagnosed with stomach cancer: the pressure of trying to entangle people with some kind of problem deeper and deeper in the web of bureaucracy struck him as inhuman, and it was a lot to ask from an hourly worker; when he changed jobs, the symptoms faded away. These aren’t even jobs where there’s an imbalance of libidinal forces: everyone, it seems, hates bureaucracy where it interacts with the public – some people might enjoy the systematic fashion in which things are handled internally, but customer service is never enjoyable.

So, if no one likes it, and it’s by definition inefficient and unwieldy, why do we do it?

Fisher would argue that it’s because we’ve accepted that there is no alternative. Our ontological and epistemic horizons have contracted to the point where we cannot conceive of not-this: Contemporary Capitalism struggles to imagine a coherent Not-Capitalism. To this, I would also like to add some analysis done by David Graeber for the landmark book Bullshit Jobs: A Theory (previously mentioned on this website here.) –

Under capitalism, in the classic sense of the term, profits derive from the management of production: capitalists hire people to make or build or fix or maintain things, and they cannot take home a profit unless their total overhead—including the money they pay their workers and contractors—comes out less than the value of the income they receive from their clients or customers. Under classic capitalist conditions of this sort it does indeed make no sense to hire unnecessary workers. Maximizing profits means paying the least number of workers the least amount of money possible; in a very competitive market, those who hire unnecessary workers are not likely to survive. Of course, this is why doctrinaire libertarians, or, for that matter, orthodox Marxists, will always insist that our economy can’t really be riddled with bullshit jobs; that all this must be some sort of illusion. But by a feudal logic, where economic and political considerations overlap, the same behavior makes perfect sense.

As far as I understand Graeber’s analysis, he is going in to what Fisher would call “the Libidinal Formation” of what undergirds Capitalist Realism: at least some parts of it are fundamentally a post-feudal system that would fit easily within the framework of Niccolo Machiavelli’s theories on domination – that is to say, many parts of politics can be explained by individuals seeking to exert dominance upon one or another of their fellows, or simply trying to avoid the same fate. The desire for a large “retinue” (read: group of subordinates) leads to an inflation of the number of people hired and employed by a company, who are employed to support the ego of their superiors.

Of course, once a person climbs high enough, their worth as an executive becomes a function of their rapacious deprivation of their subordinates of their respective retinues – it is only by this function that most corporate (read: managerial feudal; read: bureaucratic) structures avoid runaway cancerous overgrowth (as opposed to normal cancerous overgrowth.) Of course, the problem here is the reduction of an employee to a mere marker of status, objectifying a person to the point where they serve no other purpose than to inflate the ego of a superior. This is also repeated, less effectively, at a smaller level – I myself was once fired for “bad vibes” (officially speaking,) but feel that my firing was an attempted show of dominance by the owner of the company over the C.O.O. – otherwise, why would a small healthcare business fire someone who made up the majority of their HIPPA compliance team?

Mark Fisher, photograph used in the New Yorker, taken for Verso Books by Greg Gatsas

At one point, Fisher claimed that one of the best strategies that the left could foster is a coherent critique of the bureaucracy of Late Capitalism or Neoliberalism. He brought to the table the well-developed logic of “Market Stalinism” – the obsession with signs of progress or achievement over actual achievement, and the fact that it tends to hamper progress or achievement in favor of focusing on the signs of it.

Graeber articulated what I’m calling the “Machiavellian critique” of bureaucratic overgrowth; namely that it tends to exist mostly as a sort of libidinal extortion of subordinates by superiors, in the form of “managerial feudalism” where people are employed solely for the fact of their employment to serve as an ego boost to their employer, and oftentimes terminated as a show of dominance by one executive over another.

Finally, I would like to offer an addition to these other two critiques (“Market Stalinism” and “Managerial Feudalism”) by referencing the principle survival mechanism: the “Nuremberg Logic” of endlessly deferred and displaced responsibility, so that no action actually happens by the will of a human being. Taken altogether, I feel that these three factors clearly illustrate the problems with the way bureaucracy functions in our society.

All of that being said, we have examples (see: the Apollo Program, among others) that clearly illustrate that bureaucratic means can be used towards productive ends. When it functions as an extractive apparatus, given the mandate to generate profit, bureaucracy tends towards inefficiency, inaccuracy, and just-good-enough solutions (because, ultimately, those things allow it to generate more profit.) However, if freed from the profit motive, I believe that it can be a worthwhile means of generating results, principally because of arguments laid out by Graeber in his essay “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit.”

The Nuremberg Defense can never be allowed to be a valid defense, regardless of context.

I think that the Nuremberg Logic aspect of contemporary capitalist bureaucracy might represent its biggest vulnerability: people don’t realize that they’re allowing responsibility to be deferred, they don’t think about how they’re allowing monstrous acts to be gotten away with. As such, questions that insist that responsibility not be deferred become potent tools: “Who decided?” “Who picked that?” “Who says?” “Why?”

While non of these questions may function as the armor-piercing weapon to end profit-seeking bureaucracy, they are weapons that can be used to degrade the integrity and morale of the bureaucracy itself, and reveal the contradictions within it. And while, as Deleuze and Guattari say, nothing ever died of contradiction, this can lead to the structure being weakened and vulnerable to other challenges.

There are, of course, other heads to this particular hydra, but weakening it is essential – as may be capturing it and turning its methods towards other ends. While, as Audre Lorde noted, “the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house”, not all the supposed tools of the dominant power structure belong to to the structures of power – cooperation is what made us human, and writing (an ancient bureaucratic technology though it is) made poetry immortal; and, at root, these are the two constitutive elements of bureaucracy.

You just have to avoid the three traps outlined above – focus on results instead of the measurable signs, avoid retinues and subordinates as signs of status (I’d say avoid hierarchy altogether, but people tend not to listen to me on that,) and avoid responsibility being deferred.

After all, in the words of Gilles Deleuze: “There's no need to fear or hope, but only to look for new weapons.”

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)