To Live and Die by Metaphor

A raven is like a writing desk insofar as both can produce a few notes, though flat, and are only rarely approached without caws. While amusing, though, this is a less than useful analogy.

One of my favorite works of theory is The Metaphors We Live By by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson. This book argues that we structure our understanding of the world around us by metaphors that quickly become invisible to us. Their go-to example is that we look at arguments as a form of warfare: we talk about “attacking” and “marshaling” and “strategizing” when we discuss argument.

None of this is new, but they propose that using a different metaphor could result in a different mental framework – they ask how it would look to think of argument less in terms of a contest to destruction but as a collaborative art form, like dance. They contend that a society that structured their understanding of discourse as something like dance, where both parties help one another arrive at a new position, might be more peaceful but potentially less decisive.

Some of the most invisible and influential of these metaphors can be found in what they call “prepositional” metaphors, which refer to metaphors that hinge not on comparing two things, but insert a directional component. The most easily recalled of these are that height = status and forward = future. The first is fairly central to human beings, but the other one varies rather heavily from culture to culture: the ancient Greeks thought of the past as being behind you, sneaking up on you like a mugger, and I'm given to understand that in the various Chinese languages, there is a tendency to associate the future with a downward direction.

There has been a lot of noise lately – some from us – about a lack of new ideas, and we’ve tried to provide solutions. About how the very category of “the new” has been running dry recently and we've been left to circle back around and consume and regurgitate the forms of the past over and over again forever in a traumatic cycle. It may be an anemic solution, but it seems entirely possible to me that one solution for this problem is to refresh our storehouse of metaphors and examine the ones that we currently use for utility.

Sadly, no matter how much you compare yourself to a robot, you’ll never be as cool as Roy Batty.

One metaphor that I do my best to stamp out of my own discourse is the “person as machine” metaphor – we have habit of talking about ourselves as if we are robots or computers, discussing our memory as a finite resource that might get filled up at some point. I have even heard people talk about needing to “power down” instead of going to sleep. There's a tendency to treat our bodies as robots that our minds are piloting – a peculiar cartesian delusion that makes us disregard our own needs in the interest of laboring for the benefit of another (Descartes previously discussed here.)

Another one that I find interesting is the conception of time as not just a resource, but as a commodity. Before the invention of the clock, it was somewhat foolish to discuss “spending time” because time wasn't thought of as something like money – only natural philosophers subdivided time into equal chunks. For common people, the rhythms of life were a stretched out, long-wave affair that had more to do with the rhythm of the seasons than the working of a mechanism. It wasn't until industrialization, when the owners insisted on wringing every instant of possible labor from their workers that the average person became intimately aware of the subdivisions of the day. If something can be subdivided, it can be spent and made into a commodity or currency.

To incorrectly paraphrase Karl Marx: “time was invented by clock-makers to sell more clocks.”

Before that point, while it might be valuable, it could not be said to have a particular value.

I think that the best way to change our minds is to change our metaphors. If we can create metaphoric grounding for new ideas, then they will emerge. Part of the problem here is the capture of culture by special interests: when all movies are produced by Disney, and all books by the same giant publishers, it becomes difficult for new metaphors to emerge, because of the editorial voice that takes over.

If small producers of culture – groups like Broken Hands, as well as other cooperatives and creator-owned outfits – can come up with compelling metaphors to describe the dynamics in play, perhaps this logjam can be broken. Of course, the problem there is that such producers lack the necessary reach.

I'm getting off into the weeds.

Let's consider metaphors and analogies and how to create new ones.

One metaphor I find myself returning to over and over in my writing is the metaphor of the street or road as a river. Consider: the road is a channel by which things travel, which cannot be crossed easily by a human body, and the physical resemblance in the form of it being a long, narrow, and (ideally) level surface. This brings with it the baggage of a certain kind of fertility and culture: ancient civilizations almost always grew up on the banks of great rivers, because they fed the development of life.

I have also heard people talk about highway and roads and streets as being somewhat like the vessels in a body, which equates industrialized society to a body, and the movement of people and goods within it to the cells within the bloodstream that sustain it. This brings with it a certain normalization: slowing the traffic within such a vessel, especially a large or arterial vein of it, suggests death or sleep, concepts which generally have negative connotations in modern industrialized society.

What other metaphors could we use to look at a city street?

Perhaps it is an avalanche, an uncontrolled cascade of solid objects which could crush anyone and anything seeking to traverse it, but which is not a permanent state.

Maybe the traffic upon it could be likened not to a fluid but to a flock of birds, each one self-directed, but following a set of rules that allows complex behaviors to emerge without coordination.

Or possibly the street itself could be viewed as a desert, a harsh place where nothing grows and one may become lost and trapped, unable to read the necessary signs to understand the course one might take.

Perhaps it is best understood as being like the wiring of an electronic device, a channel by which something necessary passes when in use but which may at some point be switched off and put back on the shelf, to be used at an appropriate time and not put to use otherwise.

Or maybe a road is like a speech, a continuum in which a message forms, each automobile a word in Hamlet's monologue as he asks whether or not he should kill himself. A soliloquy of the city as it decides whether to continue down its self-destructive path or cease and survive.

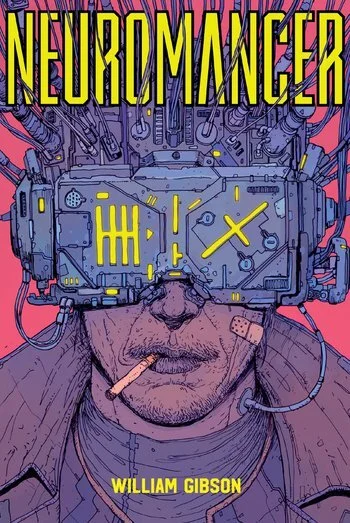

William Gibson invented the metaphor of cyberspace while writing Neuromancer on an electric typewriter, and then was disappointed with how actual computers functioned — there’s something poetic about that. But a lesson as well: the best metaphors can be crafted with less-than-complete knowledge.

I have seen some people discuss the internet or cyberspace as another dimension, a faerie-realm or hell-dimension or spectral plane that coexists and is coterminous with our lived world. The very phrase “cyberspace” calls this idea into being: viewing the other side of the screen as a wonderland with its own rules and dangers. This metaphor, created by William Gibson, may be the last metaphor to remap our lived experience in a significant way – not because it's so famous, but because it became so invisible, because it seeped into our heads and changed our thinking.

Could we make another metaphor for the internet, something other than a place? If we do so, it could defang the idea that things that happen there don't matter, could make it clear to us that we're interacting not with mad mirror-world doppelgangers of people but actual people who have thoughts and feelings and beliefs worth considering (not, necessarily, respecting: we must take what a fascist believes into consideration as a factor in our decision making, but we needn't respect a call for genocide as a valid idea.)

Perhaps we could make it a conceptual leap. I propose to you a modified prepositional metaphor. Cyberspace isn't another world, it is another direction. Think of it this way, how might your consideration of the world be if you didn't open up a portal to this other world on your phone, but if you looked webward for something.

(A side note, I'm not proposing this as a legitimate option, merely as a thought experiment.)

The benefit here is that it keeps many of the locative turns of phrase that we use – you can still refer to things on the internet as being places, but they're places in our world, not like a storefront or a library, but like the locations within a card catalog: you can go there but you can't occupy it. However, I think that this might solve the current problem, which is that people think that what happens on the internet has no repercussions – a questionable thought, but a logical followup to the idea that the internet is somehow another world: our only models for “other” worlds are dreams and fantasies, which don't seem to have any influence on our real world.

My suggestion here is somewhat selfish – Edgar and I first met on the internet almost seven years before we met in person. While neither of us considered the option of a long-distance relationship, it was always a rewarding and enlightening correspondence. As such, our relationship has the quality of two people finding each other after having met once in a dream. On the other hand, if we consider the internet to be a place in this world, we become far-ranging travelers who met while we were both in a foreign land, instead of dream-workers.

To be fair, Edgar always aspired to be as wizardly as possible, while I'm the more practical one – so perhaps both metaphors can exist side-by-side.

This is what you should imagine when you think of Edgar Mason (actually the cover of The Time of Dark by Barbara Hambly. I can’t find the artist’s name: if you know it, please leave a comment so I can correct this oversight.)

The only other model that presents itself to me as an option (other than the current model), would be to think of the internet as a kind of vapor that fills the space we're in: some places thick like fog, and some places so thin as to be absent. This would emphasize the disconnection and distraction that the internet causes from the real world (after all, sometimes the fog is so thick that you decide your errands can wait, and that text message can wait until you're parked,) as well as the uneven distribution of it.

Crafting new metaphors is a difficult task: very few of us try to do it regularly, and oftentimes, when we do, it is supposed to apply to a particular situation that will arise once and then never again – and so our metaphors are purpose-made for one thing and one thing only, and it is only an accident when it becomes more generally applied.

But a new metaphor is a beautiful and useful thing: it almost has more the quality of discovery than creation, as you uncover something that could have been made at any point in the past. Inventing something that could have existed for a long time previously is rewarding, because it shifts your whole world, opening up new ways of thinking, creating, and behaving that make it feel as if you are dreaming awake, making the whole world new.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)