The Queen's Own Brainrot: Uprooting the Long Nineteenth

The cover of the single, via Wikipedia.

“From the west to the east,

From the rich to the poor,

Victoria loved them all.”

-- The Kinks, “Victoria,” Arthur, or, the Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1969

It’s a classic jam: twangy guitars, Dave Davies’ lower vocal register, Elgar’s “Land of Hope and Glory” in there someplace. Yet another earworm from the Kinks’ late ‘60s hits, tongue firmly planted in cheek, “Victoria” is exactly the kind of mock-adulation for the glories of the empire on which the sun never set that is hilarious as satire, but all too easily repurposed as a nationalistic anthem. Ironically covered by The Fall and, bitterly, horribly, included on a War Child benefit album, it’s… complicated.

But just as Ray Davies’ lyrics play up the equally bitter ironies of the Victorian era – culturally longed-for, pre-parodied until it loops back around to love – it fails to examine what those ironies mean for us now. It’s unfair to expect it to, of course: it’s a three-and-a-half-minute pop song from 1969.

We, however, hold one end of the many-lensed telescope of reception; we are the unhappy heirs to the world the Kinks satirically hymned. And what did it leave us?

Fuckin’ brainrot.

※

I’m using Victoria Regina here as a kind of synecdoche for the Long Nineteenth Century, a term coined by Ilya Ehrenberg and Eric Hobsbawm to refer to the period from 1789 to 1914. Beginning his reckoning with the French Revolution, and charting the period up to its disastrous demise in the form of the First World War, Hobsbawm in particular drilled down on the rise of industrialization, capitalism as we know it, and socialism in a three-part string of books. A committed Marxist – for better and for worse, given, you know, Stalin and what have you – his politics certainly informed his view of the period.

For full disclosure, I haven’t read Hobsbawm, so any iteration of his ideas will in my hands be vulgar, filtered through Wikipedia and others’ views. But his and Ehrenberg’s construction of the Long Nineteenth is very useful to us now: the philosophies and ideologies, the iniquities and virtues, that found flower in that time indelibly mark the period we currently endure. To belabor the analogy a little, what flourished then makes compost for us now, the stuff we’re trying to use to make a world.

Or does it? My great-grandparents were born into the end of the Long Nineteenth, and leaving aside my family’s propensity towards having children late in life (great-great-grandpa fought in the American Civil War, if that tells you anything), that puts us a scant four generations from it. Is that all it takes for all that stuff, all those ideas and visions of how things ought to be, to get ground up into how the world is?

We’ve certainly allowed it to be: where concepts and ideas have rotted, we insist they’re still good, not that far past their expiration, it’ll be fine.

It’s not, though. This is really not fine.

※

There were a bunch of unattributed pronouns and reflexives in that last section, so let’s define them. What, precisely, came out of the Long Nineteenth that we uncritically accept?

Industrialization and consumer capitalism, for one thing. Not to be all David Graeber about it, but that stuff is recent. If we consider just recorded history, it’s a blip on the radar. But we’ll come back to that; it’s a big one. (Much of the popular concept of Europe in the Medieval period, as well as a bunch of misconceptions about ancient Greece and ancient Rome, also stem from this period, and I note this parenthetically because I ended up not having time to get into it.)

Let’s look at something a little more innocuous: clan tartans. While it’s generally common knowledge now (I think) that clan tartans are essentially an invention of the early nineteenth century, it’s worth examining how and why that particular “tradition” came about.

Please enjoy this period caricature, via Wikipedia.

If we get down to it, tartan as a thing wedded to a particular family was more or less invented from whole cloth (ha!) in the wake of George IV’s visit to Scotland in 1821. It was the first royal visit to Scotland since the seventeenth century, and was both a propaganda opportunity to try to prop up the regime of an unpopular monarch and an attempt to show royal respect for but also sovereignty over Scotland in the wake of the “Radical War,” a weeklong period of strikes and unrest in part inspired by the revolutionary spirit of France and America. It’s a bit of a complicated mess, but tartans became popular because Sir Walter Scott did the set design for the visit – and then some guys who definitely didn’t have a vested interest in tartan remaining in high demand put out a book with a Latin title purporting to be a history of Scottish dress, prominently featuring clan tartans. Despite being almost immediately identified as a forgery, it nonetheless functionally invented the clan tartan as we know it.

This is obviously a gross simplification of events, and I’m really not trying to be all James Burke over here, but the example of the clan tartan handily illustrates my point. The TL;DR of the tale of the tartan is, fundamentally Romanticism and imperialism, rutting desperately to spawn their wretched brood. It is simultaneously not that deep, and absolutely that deep, a rat king of ideology, propaganda, and blind pursuit of profit, the fruits of which feel inevitable and immutable.

※

As a sort of general aside, it’s worth noting that the vast majority of Protestant sects that have taken root in the United States have their seeds in the Long Nineteenth. Although in my first youth I entertained fantasies of a career as a Christian apologist, we’re several crises of faith away from that now – but I want to clarify that I do not mention this as a way to dismiss Christianity entirely.

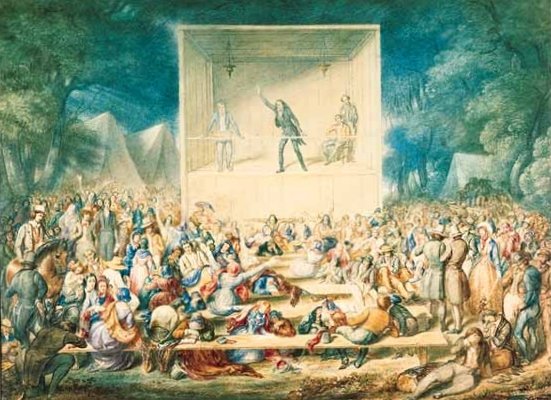

An 1839 engraving of a Methodist revival, via Wikipedia.

I do mention it though, because when we discuss “Christianity” in the context of the United States, we’re almost certainly talking about something that grew out of one of the various Great Awakenings, largely-Protestant movements that swept through the United States in waves and formed and schismed and re-formed (and reformed) popular Christianity as the country itself roiled through its violent throes. Although technically the First Great Awakening happened prior to Hobsbawm’s Long Nineteenth, it wasn’t by much, and subsequent Awakenings grew from it; discussing US political and cultural history without discussing this intense religious turmoil is naïve at best, and disingenuous at worst. But it is equally naïve or disingenuous to pretend that the reverberations of these “Awakenings” do not still linger in what Americans – and, by extension, those subject to its cultural hegemony – might construct by references to “Christianity” and “Christian values.”

Once again: these things are new.

※

It would also be somewhere between naïve and disingenuous not to at least touch on scientific racism and the cascading effect it has had on the Euro-American cultural sphere. This is not to say that racism was invented in the Long Nineteenth – but it was codified, and argued for, and deployed against non-white people to catastrophic and horrific effect. And although the roots of scientific racism extend back to the Enlightenment period, its implementation and widespread belief flourished throughout the period we’re discussing here, especially as the British Empire straddled the globe, spread not only through military intervention but also through extractive industrialization and a variety of ostensibly charitable projects that extended the cultural reach of the empire.

The impact of scientific racism as broadly accepted fact is difficult to overstate: it impacted Euro-American society in almost every way imaginable. From gender to education to the many genocides of the period, its pernicious influence, especially coupled with evangelical approaches to Christianity, is literally everywhere, and it was used throughout the period in question to justify many atrocities. While the Long Nineteenth may not have invented scientific racism, it did come close to perfecting it, with all the horrific implications that entails.

I am not the best-qualified to discuss the insidious effects of racism, scientific and otherwise, throughout this period. But I think “insidious” is truly the word for it, in the Long Nineteenth and beyond.

※

Child laborers in a textile mill, 1909, from this truly weird Encyclopedia Britannica article.

Industrialization and, as an attendant demon, consumer capitalism came also from the Long Nineteenth. We all talk a lot about the Industrial Revolution, as well we might, but it is worth remembering that that too is just not that old. The very concept of shopping as a leisure activity was invented in this period, and all those yards of fabric for the hoop skirts we all mock didn’t just appear out of nowhere. It was made and it was milled and (because ready-to-wear clothing postdates the period of the hoop skirt, by and large) was worn into the ground by people who didn’t wear skirts like that because they had other things to do.

Without industry as we understand it, you can’t just go buy stuff. I mean, you could, but you needed to have the money to do so (or, pace Graeber, a credit arrangement of some kind), and if when you did, unless you were one of the dazzlingly wealthy, you used it until it was no longer usable or you died, whichever came first. There are obvious problems with this – one broken item that you use every day becomes even more of a financially-devastating prospect than it is now – but it was the Long Nineteenth that gave us the singularly extractive, environmentally-damaging approach to making stuff fast and as cheaply as possible that we have today.

And by extension – by virtue of advertising as a coherent class of public discourse – we want that stuff. We want it now, and we want it cheap, no matter the environmental or human cost.

※

If I tried to chart everything given to us by the Long Nineteenth century, I’d be here all day, and I have other things to do. I’ve also skipped over some good stuff, like hand washing and George Eliot, and I’m not trying to be Lytton Strachey here. Besides, that would be talking around my point, and I’ve done plenty of that.

Not even the worst offender, with respect to facial hair, but this guy is one of the guys behind the Daily Mail, and his photo comes also from Wikipedia.

My point is, many things seem like facts about how the world is and has always been. That last clause is key here: the ideologies and practices discussed in this piece are positioned as if they have always been the case. And it’s not true! It’s not! It never has been, and half of this stuff was put forward by guys who thought doing that to their facial hair was also a good idea! We don’t have to agree with the concepts that Euro-American ideologues of the Long Nineteenth presented, and we certainly don’t have to take their word for anything.

To use an analogy: you are trying to remove weeds from a patch of land. The weeds are many; they are an invasive species, and they will flourish and choke out anything else if you do not remove them. The task seems daunting – and it is. The patch of land is large, and only looks larger when you get down to begin pulling up all those weeds. But as the first little clump of diabolical flora comes up in your hand, you realize that the roots only extend a few inches into the ground. The task is still great, but it is not as intractable as it seemed at first.

So I guess this is my point: where you find what seem to be deleterious ideas about “how things are,” get down and examine their sources. You may find that they are far less-deeply rooted than they seem.