The Bound-Like

I feel bad that I cannot properly discuss the game Hylics in this piece — I’ve just started playing it, and it seems to be working in a similar vein and to be far more self-consciously and intentionally surreal than the rest.

The original version of this column was written for the third odd columns, but I got distracted (for good reason: this was technically our third odd column), and never posted it. I’ve had a week and it’s only Wednesday, so I’m fixing it up now.

Occasionally, we discuss genre, and largely this is limited to film and literature, but there’s a particular problem with looking at the use of genre in a ludic context. In short: video games handle genre in a decidedly weird fashion, and it’s worth commenting upon.

In writing on video games, I was reminded again of Studio Ackk’s YIIK: A Post-Modern RPG. It’s a game I’m still a little disappointed by, given that it showed such promise beforehand, and was so visually striking. In all honesty, I’m hungry for video games that combine a contemporary setting and a non-organizational perspective (most video games set in the contemporary world cast you as members of some larger organization, able to draw on their resources when you’re in trouble; even my 2019 game of the year, Disco Elysium does this.) Thinking about this, I determined that most RPGs set in the modern day and where the characters are working without organizational backing fall into a tightly clustered set.

A screenshot from the original Rogue. It’s quite an old game. Image posted by user Thedarkb on wikimedia commons and used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Usually, in discussion of video games, the “-like” suffix is reserved for games that share a mechanical affinity. The Rogue-Like is a top-down dungeon crawler where the map is randomized and death is easy: you have to create characters regularly to go and collect the treasures that were left behind after you died and this is exacerbated by the fact that the map changes every time you do. The Souls-Like is a variation on this formula created to describe Dark Souls and similar. These games after often also Rogue-Like, but feature the mechanic that you have to collect a currency from defeated enemies to advance your character, often feature a punishing level of difficulty, even on easier settings, and tend to play out the larger plot that you’re a small player in through dropping tidbits in item descriptions and other optional bits of text (a non-souls-like that does this effectively is Alexis Kennedy’s Cultist Simulator – which is sort of a slot machine that produces some snippet of Kennedy’s writing every time you pull the metaphorical lever.)

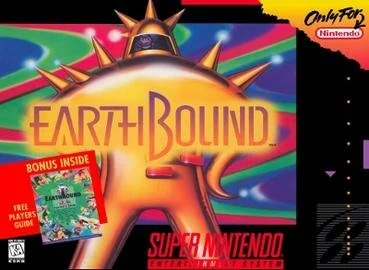

The box for the original English version of Earthbound, used without permission. The Nintendo aesthetic really belies the content of the game.

The sub-genre I want to describe is something I’m calling the “Bound-like” after the archetypal example of EarthBound, an SNES-era RPG that is best described as “H.P. Lovecraft’s Peanuts”. To make the comparison most apt for us: if, in the pantheon of Nintendo games, Super Mario Brothers, The Legend of Zelda, and Metroid are, respectively, equivalent to Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, EarthBound is the Doom Patrol: weird, uncomfortable, and beloved. While it had a limited impact when it was released, it’s had a major influence on the Western indie gaming scene. I would argue that most Bound-Like games tend to derive from the two canonical Japanese examples: EarthBound and the Shin Megami Tensei: Persona series (largely the ones from 3 onward.)

There is little mechanical affinity between them: almost every example I’ve seen is a JRPG, featuring turn-based battles played out through menus, interaction with NPCs in a neutral location, and dungeon exploration with enemies visible on the map. From a mechanical perspective, there isn’t much to differentiate them.

But there is a definite aesthetic distinction: there is a modern setting, a lack of organizational support, a focus on psychodrama, “quirky” humor balanced with real pathos, and usually a fair amount of genuine horror. Usually the thematic component has to do with warped perceptions of the world and the importance of social connections in confronting dangers bigger than ourselves.

As mentioned the archetypal examples are EarthBound and the Persona sub-series of the Shin Megami Tensei series. There are a number of other games out there that fall within the same general narrative space. As mentioned, YIIK technically falls into this, but design and narrative decisions made in the game rob it of a lot of the enjoyment.

The title image really captures it all.

On the other hand, Jimmy and the Pulsating Mass is implicitly about a young boy in a coma traveling through a dream world to emotionally process his impending death due to cancer, and there’s a special kind of horror at the decay of this childish setting and the nightmare logic that wells up from underneath. The main character’s special power is explicitly said to be empathy – it is through empathizing with your enemies that you gain the strength to face future challenges, but at the same time there’s only so much that can be done in the face of impending mortality.

Fitting into this same general pattern is LISA: The Painful, which is simply described on Steam as “The miserable journey of a broken man.” The world has been destroyed in a gendered apocalypse – all women die off mysteriously – and the resulting all-male society is a broken and incomplete thing as a result (it seems to me to be a parody of the MGTOW thing – all of them are so emotionally stunted that they revert back into tiny bands of people.) Before the collapse of civilization, the main character was a karate teacher, and shortly after the apocalypse, he found an abandoned infant girl. He and several other men become surrogate fathers for her, and then she’s captured. The whole game is kicked off by her kidnapping.

Recently, I played the demo for a game called She Dreams Elsewhere, which is a low-fi game about a young woman who is struggling with anxiety and depression who gets pulled into a surreal dream world and pursued by horrific monsters. As she goes on, her friends from the waking world show up and offer her support in battle against them. There’s not much out there about this game, but I enjoyed the brief demo (including the uncomfortable party scene,) and all of the save points are dogs, so there’s that.

The batter, from OFF!

Then there’s Off! – this is a more abstract, surreal game, originally from France (if memory serves,) where a spirit in the form of a baseball player is dispatched to strange, elemental realms (not the classical elements: smoke, plastic, metal, flesh, and sugar) to “purify” them. This game is notable for the strange visual style, which is among the more dream-like and odd.

A more notable recent example might be the recent free JRPG Get in the Car, Loser!, which is essentially a visual novel that makes you play through a couple-three turn-based battles between scenes. Notably, this one draws on a different kind of strangeness, melding eighties-nostalgia and contemporary queer culture into a more feminine – and specifically lesbian – take on the genre.

An argument could be made that Yume Nikki (the title of which translates to “dream diary”) is also an entry in this genre, but it is more of a non-linear adventure/puzzle game exploring the trauma-dreams of a young woman named Madotsuki than it is a traditional RPG.

Of course, the entries that most map on to the genre I’ve laid out would be EarthBound and Person, with YIIK and She Dreams Elsewhere being closer to the heart of it. Jimmy and the Pulsating Mass and LISA would be more fringe, while Off! is slightly closer and Yume Nikki forms the most separated edge case.

If there’s a more distant fringe, a “Bound-Lite” similar to the “Rogue-Lite” or “Souls-Lite” genres, Yume Nikki would slide into that, it would include games like Citizens of Earth and it’s possible that Disco Elysium might qualify as the outermost edge of that particular narrative space, though it completely eschews the JRPG interface for one heavily influenced by Planescape: Torment.

The essential generic traits – the paradigmatic or mythic ones, if you will – could be enumerated as follows:

A contemporary or largely contemporary setting: Persona 5 is set in Tokyo, but the other games in the series are set in fictional locations, and Earthbound is set in the country of “Eagleland.”

A supernatural element that is not positioned as an ancient secret, but instead as a novelty or intrusion from elsewhere.

The protagonists form a group in a more ad-hoc fashion (or, if we place Disco Elysium in a “Bound-Lite” category, then some room could be made for the protagonists being largely separated from any institutional support that they might otherwise receive.)

A visual and narrative style that edges into the surreal.

Despite increases in strength and power to confront weird threats, the texture of everyday life remains intact for the protagonists, whether they maintain contact with it or not.

An emphasis on prosocial bonds between the protagonists, as well as between them and a larger community, often taking the form of a responsibility felt towards that larger community.

The emphasis, while often including confronting a weird threat or defeating an evil, is often aimed more at uncovering a secret.

A tone that vacillates between the dramatic and the comic – oftentimes, the humor arises less from absurd situations (which do arise, but which tend to be handled in a more straight-faced way,) and more from the characters responding in a realistic fashion to the absurd situations.

I’d have more examples – because I know they’re out there, but unfortunately Steam’s recommendation engine basically just suggests that I should buy Octopath Traveler and Dragon Ball Z games (I’m very salty about how the changes to that particular system unfairly impact independent creators.)

Why is this notable? one might ask. I would argue that genre tends to serve a two-fold purpose: it was instituted by advertisers to differentiate between products and more help connect “content” to a particular population that might be interested in engaging with that content – thus far, genre distinctions in video games have been solely the province of marketing. Any analysis has been stunted by a somewhat unusual refusal of the critical community to make too many statements about it – and thus genre has been a placeholder for “gameplay” or “interface” – more closely mirroring the division between fiction, nonfiction, and poetry than between, say “the detective novel” and “the western novel”.

This has created a situation where, as I described to Edgar, it is possible to get the equivalent of a collection of sonnets, but not a collection of love poetry. In most situations, our culture over-privileges content, to the exclusion of form. In the area of ludic studies – criticism focused on games – the reverse has largely been true.

If games are an art form, then it must be possible to talk about what they say, instead of just how they say it: and while we often ignore how things are said in day-to-day conversation about media, pretending that nothing is being said – that these games are utterances completely sans content – is jarring and offputting.