What is Identity?

The False Mirror (1928) by Rene Magritte. The surrealists were early thinkers on this topic, but communicated their insights strangely.

In all the maundering that I’ve engaged in on this blog, there’s a fundamental question that I have only briefly touched upon: what is identity? More basic than this, is a question that I have barely touched upon at all and yet remains near and dear to me as something I’d like to work upon: what is subjectivity?

Subjectivity and identity are intimately connected, but in my reasoning, they’re the interior and exterior representations of the same thing. But the nature of this thing being represented is unclear.

My intuition is simple: identity and subjectivity are ways of talking about a process – what the Situationist International might call a practice of everyday life. The process of selfhood is complicated, and perhaps over-theorized: many leftists hold on to a certain amount of Freudian ideas, on the grounds that there have been many Freudo-Marxist thinkers over the course of the 20th century. While I’ve turned the corner on a number of Freudian ideas, I’m not exactly the biggest fan of Freudian thought.

So I want to think a bit about what the process of selfhood entail, because it has both political and aesthetic implications – in short, it might have implications for the project I’ve taken up and for the project that this website was formed for.

I’ve been meaning to deepen my knowledge a bit. Our local bookstore had a copy of this book, the Diné Bahaneʼ available, actually translated by one of my old professors.

I’ve already talked about how I feel that identities are inscribed upon us: what it means to be “white” in America is different from what it means to be “white” in France, Germany, or Poland (and despite grouping those three together, my understanding is that it means different things for the inhabitants of those three countries.) Likewise, what it means to be a man or a woman differs between cultures – those two categories are not stable, with a number of other cultures (including indigenous cultures,) having additional categories, such as the Navajo nádleeh, who don’t fit into the gender binary (I refer to the Navajo because I have slightly more experience with Navajo culture than other indigenous cultures. I cannot speak authoritatively on this, however.)

In short, I have discussed identity as something inscribed upon a person, but the nature of that inscription has been left somewhat blank. That’s primarily due to the complicated nature of identity: people are free to behave as they will, but what we will is somewhat pre-determined. This isn’t to say that we aren’t free to choose things, but that our identity makes it more likely that we will choose different things. It is unlikely that someone socialized as heterosexual, for example, will engage in a homosexual relationship – but this is not a given, it is a matter of probability. One is more likely to do one thing than the other, but this isn’t a given.

This is a binary thing – yes or no – on the level of the individual. On the level of population, it becomes a matter of proportion – while the majority may say yes, there will always be some who say no.

There are, obviously, variations among a population, and this has to do with how we respond to what we experience. However, it is a mistake to think that a single person is necessarily a unitary thing: in Deleuzoguattarian thought – and I think this is true – we are all bundles of often-contradictory desires. Sometimes there’s enough of a quorum to make things easy: 98% of our desires are aligned with something. Sometimes it’s not quite so clear cut. This lines up remarkably well with what we know about the brain’s material functioning, but it is incomplete. I’ve stressed a number of times that consciousness is not enthroned in the brain but embodied, and that it springs from not just our human cells – brain, vagal nerve, spinal column, adrenal glands – but all of the fauna that lives within us. A human being is not just an alliance of human and inhuman cells, but a complex ecosystem with a porous border.

I want to emphasize this because I fear that my description of identity will sound machinic and cold if I don’t emphasize it. Because my thinking on this matter – the more-objective end of the process of selfhood – is extremely simple in basic description, but repeated massively, sequentially and in parallel, it may take on the character of computation, and I wish to head that off because I find computational metaphors of consciousness to be overly simplistic, and reducing the human down to the level of mechanism seems vulgar to me.

Deleuze and Guattari referred to these processes as “machines”, and this is how they interpret the machinery of Immanuel Kant’s identity. Doesn’t make much sense to me, but I don’t really know where to begin.

Deleuze and Guattari suggest that desire (pre-, post- and unmarkedly capitalist) is different from how it is commonly perceived. The normal perception is that desire is a personal lack, the recognition of a deficiency in the self. Their theory is that desire is a productive force: something that provides momentum toward a particular end. My idea of the identity is founded in this – their description of the unconscious mind as something more like a factory than a theater, because a factory processes and shapes raw materials into a finished product.

Ergo, my idea is that the identity is a series of transformations, that it is an extremely long and convoluted set of instructions carried within us and which we apply to our actions in response to the world around us: when you see a red octagon, stop moving forward. When someone invites you for a drink of a liquid that makes you more awake or less coherent, assume you’re socially closer than you were.

If it were just this, the above would just be a Deleuzoguattarian restatement of behaviorism. This is not my read of things, however – because these transformations are self-referential and work upon a meta-level. It’s not simply that we learn to learn, or that we rewrite the rules of thinking, but that we occasionally will go so far as to rewrite the rules that tell us how to rewrite. Of course, as many have no doubt said, this is a sort of palimpsest: the old rules aren’t replaced but overwritten – there is a remnant of them left that can be suppressed but is never eliminated.

This is what I think identity is, rules inscribed upon us that we are free to rewrite, if we learn how to do so. These rules aren’t simply behaviors, they’re also the various moves that make up the repertoire of creativity. We tend to get wrapped up thinking about tropes and conventions – the pattern of words in a poem or short story (the Clarion Workshop’s tendency towards the construction “the X of its Y-ing”, for example), the way that light and figure are rendered on canvas, and so on – but this is all culturally bound. These “rules” that we think of are the product of the actions of culture and are, ultimately, the product of people’s decisions.

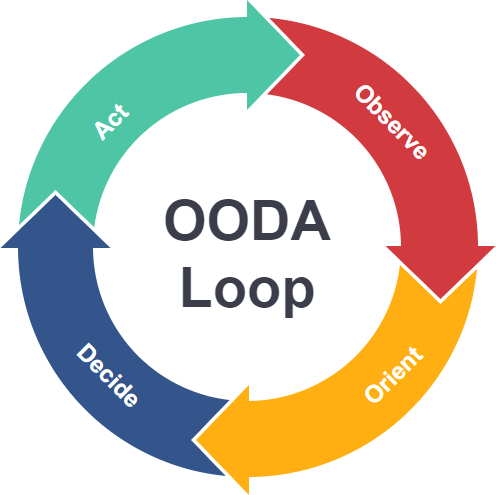

However, art – and especially stories – is also information being brought in: they’re data points taken in by the senses and processed and transformed into experiences and behaviors. In the discourse of military theory, there is a discussion of something called an “OODA Loop”: the pattern of Observe-Orient-Decide-Act, which has implications beyond military theory. Fundamentally, what we need to acknowledge is that people take actions based on what they perceive in the world. However, what the OODA loop brings in to the discourse is the “Orient” step: we apply our prior knowledge, including cultural knowledge to the situations that we perceive. If someone’s ability to observe – such as if they perceive the presence of something absent or the absence of something present – and orient – such as if they apply an incoherent or simply inapplicable bit of knowledge, or if they aim themselves at a meaningless goal – is disrupted, then their actions take on the cast of irrationality.

This is where behaviorism falls flat: it assumes no interiority on the part of its subject. If we are considering an organism with limited interiority, such as a flatworm, insect or rat, then the conclusions of behaviorism might be true enough. If we move up to an entity with a greater degree of interiority, such as a human, cephalopod, corvid, cetacean, or elephant, then the conclusions will be less correct. This isn’t simply because an intelligent creature can think through its problems and leap to a novel solution, but also the fact that culture acts as a storehouse of strategies and inherited wisdom. What enables this is language: and even if it may be less sophisticated and nuanced than human language, I don’t think there’s much dispute that the other four categories of creature in the second list have some variety of language.

Because we have human art that we recognize, we know a lot more about the interiority of human beings. We know that each person contains a vast and rich inner world (I cannot comment on the interiority of those other four, beyond saying that I assume that it is present and reasonably sophisticated.) However, we can know that the relative storehouse of knowledge available to human beings is vast.

This storehouse doesn’t simply hold knowledge, it holds the constituent pieces of identity: ready to be picked up by a person and modified into a strategy for addressing the world as presented to them. These constituent pieces aren’t simply cultural factors, they’re also personality traits: and while some people may argue that identity is set and fixed (“that’s just the way that I am”, or “I’ve always been this way”, and so on) this always rings hollow to me. There are factors that limit our options, certainly, but we also have strategies for working around these limits, for trading them for another, different set of factors.

Most interesting to me – and part of this is due to secondhand exposure to Edgar’s own intellectual project – is translation. At some point in the near future, I’m looking to write a piece on the Japanese iteration of the contemporary fantasy genre (which is near and dear to my heart, but quality examples reach us so infrequently,) and so the question of translation is always going to be present.

This is not the only venue in which we find translation, but it is the one I’m interested in. However, one can also look at other translated works and see similar phenomena. Consider Jean-Luc Goddard’s Alphaville (1965), which is a hybrid of hard-boiled film noir and dystopian science fiction.

I love how beaten to shit Constantine looks here. That’s what a leading man in a French detective movie is supposed to look like.

Let’s consider: “film noir”, despite its name, is fundamentally an American genre – the first agreed upon example, The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), may have been directed by a Latvian-born Soviet expatriate, and its earlier antecedents – the films of Fritz Lang, the fiction of Dashiell Hammet and Raymond Chandler – are not simply American, but specifically west coast, and formulated in response to British cozy mysteries. In short, there is what can be called an antagonistic work of translation at work here, even if British cozy mysteries and American hard-boiled fiction use the same language, there’s an element of cultural translation at work here.

But we’re getting far afield from Alphaville.

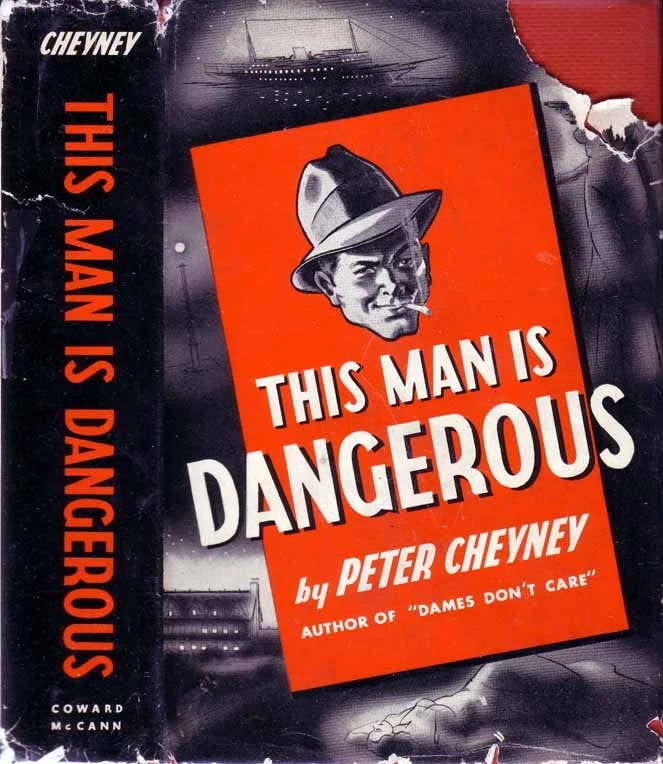

There’s this residual American-ness to the story, partially brought along by Eddie Constantine, the actor playing the central character, Lemmy Caution. The character of Caution was actually created by a British author, Peter Cheyney (the first of these, written in 1936, This Man is Dangerous, was about Caution as an FBI agent, harkening back to the American roots of the hard-boiled fiction genre.) However, Alphaville takes Caution out of Cheyney’s milieu and places him in an ostensibly science fictional setting: no special effects are used to display the new planet or its galaxy (though this is a pun – Caution arrives in this other city by Ford Galaxy.)

In short, despite talking extensively about the future and other worlds, none are on display. What the film becomes is an extended meditation on the dislocation of living in the modern world: the sentient computer that rules the titular metropolis, Alpha 60, was created by a Doctor Von Braun (evoking the former Nazi rocket scientist) to manage the city, and proceeded to eliminate such “contradictory” things as emotion and feeling, making the city an inhuman, alienated place.

Meanwhile, the cover of the original book, This Man is Dangerous, shows Caution as exactly what you would expect a British policeman to assume an FBI agent should look like. next to no resemblance to Constantine, other than the smoking.

As an American who doesn’t really speak French (I’ve got it on Duolingo, but I’m not terribly good at learning languages, I’m discovering,) I can only experience this work as a translation of a translation of a translation. When I watch it, I read the subtitles in English. However, the French film is a linguistic and cultural translation, cobbling together a new story from the work of the British Peter Cheyney, who created a cultural “translation”, depicting an imagined American FBI agent.

The standard line of thinking is that this should represent only a fraction of the film’s “true” meaning, saying that it should be held up as a mutilated classic, it’s “real” message obscured by layers of translation warping its meaning. I should not be able to derive meaning from it. Cheyney translated the American hardboiled mystery – an evolution of the gothic novel – into a sort of America-understood-by-Britain. In prior French film adaptations, this became America-understood-by-Britain-as-seen-from-France. In Alphaville, by creating a unique and new story, Goddard collapsed it down: this was Anglo-America-understood-from-France, and I have the chance to see it through the lens of a competent a workmanlike translation.

But at this layer the original “meaning” – if such a thing is real or valuable – has been refracted and diffracted and warped and adjusted to the point where it may be lost, but this is not because the work is poorer for it: instead, it is because the work has been added to so much that there is an abundance of meaning present.

You may say, at this point “well, that’s interesting...what does it have to do with identity?”

I’m admittedly taking a long walk, but I’ve stated before that I think that the media that we consume shapes how we think about the world. There’s a reason that basically everyone you meet behaves as they do: experience and cultural factors have taught them to behave that way — that’s essentially why a statistically significant portion of Americans are annoying: they think they’re supposed to act like the characters they see in sticoms.

But it’s a complicated thing, the process of forming an identity, and is much the same as translation: how we live is a translation of what we have been given as history and culture into our own lives. It isn’t going to be a completely faithful translation, but that’s okay: after all, some of the poorest translations are exact, word-for-word reproductions, taken from the original language to a new one.

This is all contingent, and if we refuse to allow our own interpretation and elaboration room to work, we will simply be minor variations on who we were raised to be. That, it seems to me, is denying us agency and refusing to take ownership of who we are.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)