Chronos and Kairos: Time in Prose

Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931). Dalí conceived of time as being “hard” or “soft” — this is perhaps a more accessible phrasing than my own, but I worry that it might be as opaque as McLuhan’s “hot” and “cold” conception of media.

I’ve been giving more thought to the practice of writing fiction lately. This makes sense – we published one of Edgar’s novellas, and I’ve got one of my own that I need to tune up this summer so that we can get it out. For this reason, my mind has been occupied by the mechanics of prose fiction.

Over the past few years, I’ve talked about a number of art forms – I’m mostly concerned with prose fiction and roleplaying games, which take as their media language (though differently than poetry; I’m not exactly the person to ask about poetry. I like a fair amount of it, but I’ve never really been a poet) and the social contract, respectively. Other art forms use other media: the medium of music is sound, the medium of painting is the application of pigment to a surface, the medium of sculpture is the stone, metal, clay, and other materials in which the artist works, the medium of theatre is the space of the stage, and the medium of film is time itself.

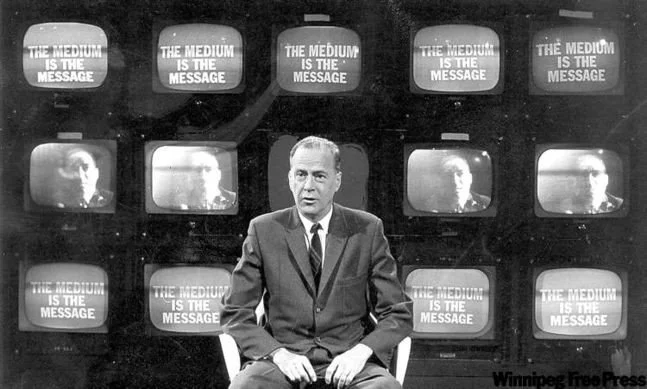

According to Canadian Media theorist – and my great-grandfather in intellectual history, being the mentor of my principle professor’s own teacher – Marshall McLuhan, every medium has as its content another medium: the content of typography is writing, which contains speech, in turn. What needs to be acknowledged is that every medium exists as a node in a sort of web, and changing one leads to shifts in all of the others. There was a time when film wasn’t viewed as principally a container for dramatic performances, though this is the obvious and logical thing to us today. It bears noting that this is not inevitable: in truth, some famous directors approach it through other frameworks, such as David Lynch’s famous conception of film as an extension of painting.

What seems obvious to me is that, around the time that film was emerging as an art form, the construction of prose fiction changed rather dramatically. The primary difference of most 20th Century literature from 19th Century and earlier literature is the filmic quality. Compare the stylistic quality of Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald (neither of whom I’m that big a fan of) to Dostoevsky, Dickens, and Melville. The later authors approach things in a much more film-friendly fashion, and there’s even – in my opinion – a patina of the filmic overlaying 20th Century holdouts of the older style – James Joyce, H.P. Lovecraft, and William Faulkner leap to mind.

My intuition is that film becoming a touchstone for Modernist and Post-Modernist writers introduced a certain symbolic vocabulary best exemplified by the dictum “show, don’t tell.” While my own style tends pretty heavily towards a filmic approach (emphasizing sensory detail and a certain diachronic representation), I’m somewhat frustrated, because the “show, don’t tell” advice seems to actually be pretty heavily ideologically weighted. Simply by conceiving of things as working somewhat like film, it becomes inevitable that the atomized, individual perspective encouraged by the mechanical eye of the camera encourages the formation of atomized, isolated individuals.

So I’m beginning to work on a way of articulating how time works in fiction. Last night, during a meeting of my writer’s group, discussion turned toward this issue. I’m going to elaborate a bit on what occurred to me during that discussion here.

In everyday life, we experience time in a commonplace fashion – what the Greeks might call chronos. What is communicated in fiction is time given meaning – what I’m going to articulate in the terms of “sacred time” and call kairos. I cannot tell you how chronos and kairos work at this point, but I can tell you how they’re experienced.

Firstly, part of why film works for human beings is that we experience the world in a discontinuous fashion. This is something that was articulated in Oliver Sacks’s The River of Consciousness, based on the author’s familiarity with dysfunctions of the brain and his examinations of a number of conditions including motion blindness. Both chronos and kairos have this quality. There are, however, some principle differences between them.

Before I continue, there are two important prefixes to keep in mind: “dia-” and “syn-”. Both ultimately come from Greek. “Dia-” means something like “through” (compare “dialogue”, meaning “through words”), while “syn-” means something like “with” or “together” (compare “sympathy”, where the n becomes an m for...reasons, which means “suffering together”). I’m also going to be forming words where “chronos” and “kairos” occupy similar roles. The basic idea here is that “chronos” is “clock time,” whereas kairos is something like “perceived time.” I hope that this clears up any confusion.

One of the first mechanical clocks that allowed for longitudinal adjustment — a potent symbol of chronos, and an important tool for the formation of empire.

Chronos time is made up of segments of uniform duration, but it is given flexibility by the fact that events can be diachronic (sequential) or synchronic (simultaneous). With Kairos, the segments expand and contract in dimension – a longer paragraph feels “slower” than a short paragraph, meaning that a longer paragraph can work as a sort of “slow motion” effect – but portraying synkairotic events is, in my opinion, perhaps so difficult as to be impossible. Ergo, while the events we experience in our lived life can be diachronic or synchronic, I’m not sure that we can read fiction that functions in anything but a diakairotic fashion: you can only really read one thing at a time, though you can have razor-thin slices of time depicting events separately in such a way that they appear to be almost simultaneous.

Part of the problem with synkairotic representation is that events are not solid things: if you’re paying attention to an event and there are multiple moving parts, it’s still one event. It’s simply an event that is somewhat complex. Given how you may have to read and reread something to understand what’s happening, this means that synkairotic events break apart and turn diakairotic.

The closest one gets to a synkairotic representation is something like Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves or Samuel R. Delaney’s Dhalgren, books in which multiple simultaneous narrative threads play out separately on the same page. This is hampered, of course, by the fact that the act of reading imposes a sequentiality on the experience. It approaches the limit of the synkairotic, but never actually achieves it.

The fundamental unit of chronos is the second – it can be broken down further and further, down to Planck’s Duration, all the way down at 5.39×10−44 seconds. Without getting into the shenanigans of relativity, within a given frame of reference, it’s always the same time, marked by the ticking by of one second to another. A second, much like McLuhan’s lightbulb, has no content of its own. It is all-encompassing and asemic.

The fundamental unit of kairos, on the other hand is the event. If you are telling a story, and you give equal weight to your protagonist brushing their teeth as you do to their death or them coming to terms with their feelings, then you are using prose in an unusual and potentially artless fashion. In prose, events of little import disappear, forming a sort of fluidic medium of things we assume happen that are broken up by little islands of significance.

That’s the principle difference between an event and a second: presumably, there’s been a second that passed when nothing important happened anywhere. Such a second is generally ignored in the kairotic mode of prose, sinking into the background. (Consider: how often in The Great Gatsby or some other, better, novel is it mentioned that someone went to use the bathroom? Either Nick Caraway and those terrible people he spends all of his time with have bladders carved from diamond, or it’s happening but it’s not mentioned. We tend to presume the latter. If the former, then perhaps Fitzgerald wrote one of the best bizarro books of all time avant la lettre.)

The moon glimpsed through tree branches — an excellent symbol of kairos, but a complicated one, given the moon’s status as the closest thing we have to a natural calendar. jansku136/Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

In this way, prose may more closely resemble a dream than it does film or lived experience. Spans of time in which nothing significant occurs disappear – of course, unlike dream, prose fiction is structured by a conscious mind that can weigh and determine significance beforehand, as opposed to retrospectively determining what the significance of the image or event in question is.

Anyone who has attempted to recount a real event in prose has had to struggle with this: what is happening is, fundamentally, a translation from the semi-natural, chronological mode to a completely artificial (or, rather, culturally constructed) kairological mode: you remove the events from the seconds and refashion it as a representation of something.

Film, on the other hand, attempts to be a sort of bicameral (pardon the pun) chronos-kairos hybrid of time: the depicted moments are all chronological on the frame-by-frame level, imitating the ticking by of the seconds and their sub-components. The grammar of scenes and acts, though, is pure kairos: it becomes kairos expressed thorugh the medium of chronos.

When literature attempts to imitate the filmic mode, it does something else: it layers the grammar of this chronos-kairkos hybrid over the pure kairos of prose, creating a kind of symbolic pidgin.

The syntax is the top of this, the paradigm is the bit underneath. Admittedly, I’m only including this on the off chance that an archived copy of this blog is the only thing that survives the death of civilization and people want to know what an iceberg looks like after they figure out how to open it.

Due to the need of a work of prose fiction to meet its audience where it is to be considered successful, I’m not sure it’s possible or desirable to pry the chronological from the kairological base. However, I do think that understanding that the chronological is a syntagmatic feature – a surface trait – and the kairological is a paradigmatic feature – the deep structure – is useful.

When writing, it isn’t a good idea to get bogged down in the matters of duration for everything: how long it takes to walk a city block, for example, is very rarely an important question for prose fiction – it isn’t essential to always keep in mind that the average human walking pace is something like three or four miles per hour and the average city block is one-eighth of a mile, giving a rough duration of between 2 and a half minutes and one minute fifty-two seconds for the trip of one block. It is only when the story requires the tension of the ticking clock that this sort of issue really matters.

Different forms of prose, I would argue, require different amounts of chronological layering: while the basic form of the prose story might require roughly the same amount of kairotic events, a novel or other, similarly long work will require more chronological “padding” to stretch it out and contextualize it. At the other end of the spectrum, you might have something like a prose poem – something that barely qualifies as prose as we think of it, which has nearly no internal chronology, but communicates a similar depth of feeling.

So, when you sit down to plan out your story, your first thought should be of the key events that need to be recounted. These events are the fundamental building blocks of plot – not, I should note, of your story: the construction of character is a separate matter, and one that is beyond the purview of what I’m talking about here (honestly, also, one that Edgar tends to be better at than I am. Perhaps I’ll try to convince them to write something about that in my stead). You should give thought to how to pace it in terms of how much the chronology intrudes on the kairotic events: how much each needs to be spaced out, and how granular you want to get with it.

Of course, I don’t believe that a prose medium can ever be purely chronological – the impossibility of synchronic representation is something of a hard barrier there – but certain works can approach that limit extremely closely.

It is my – perhaps incorrect – intuition that this has to do with the way that the human mind works, the way that we pay attention to things, and how focused that has to be to really qualify.

Of the two, Salem’s Lot is the only one I have read. I know, I need to correct this.

This feels like it’s going somewhere, but I don’t have the ultimate destination mapped out yet. Let’s circle back to something – the change in how time is directly handled in prose. Consider for a moment the difference between Dracula by Bram Stoker and Salem’s Lot by Stephen King, two vampire novels published some 78 years apart. The first is an epistolary novel, with events dripped out in documents composed by the characters (excerpt found here). The second is told in a fairly close fashion, inviting the reader to imagine it as a series of events in progress, like a transcription – with added detail – of a film (found here).

The novels are distinct, but in a summary of the plot they are identifiable as the same genre (the classic flavor of the vampire novel), when read they are not experienced in anything like the same fashion. The stories proceed by beats that have a genetic relation with one another, allowing us to see a family resemblance even if they’re not identical, but the communication of those beats is extremely distinct, ultimately taking the novels in different directions and making the experience of them distinct.

I think that – as mentioned – this is an evolution to help the novel match the desires of the audience. After the public had been exposed to film, there was a shift in what was desired out of other media. It would make sense that exposure to television would intensify this – a move towards understanding the world only in terms of outward appearances, rather than in terms of the shadowy recesses of a person’s mind. Drama attempted to capture this internality with the aside (exemplified best, I believe, by Hamlet,) Film and television skip this, opting instead for the voice-over (I will not be re-litigating the voice over in Blade Runner; I think it’s bad, Edgar thinks it’s good, this is my piece, so I’m going to accept it as truth that it’s bad.)

But the blurring happened the other way, as well: the novel changed, much like the computer later changed with William Gibson’s introduction of the neologism cyberspace, and it became not a container for the language act but a container for an image simulating space and time, along with all that rides along with that.

Perhaps this is the direction in which all narrative art is evolving – a change in the conception of narrative, itself. However, I’m running out of steam, and so will return to this discussion at a later point.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)