Cameron's Book Round-Up: Fall Part 1

I wish I had time to do something more in-depth this week, but I’ve read a lot since my last one of these and I’ve worked a lot since my last one of these; as a result, my head is empty of original thoughts but I’ve got a lot of opinions.

So let’s put those out to air and see if we can clear some space for original (to me) thoughts.

All links go to bookshop.

※

Another University of Minnesota Press book.

The Forbidden Worlds of Haruki Murakami by Matthew Carl Strecher.

Strecher is a Professor of Literature at Sophia University in Japan (a Jesuit University located in Tokyo.) This work of criticism is an excellent primer on the work of Haruki Murakami from the period immediately post-Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage. In addition to offering a critique of the author’s work, Strecher also does a bit to situate him within the larger world of Japanese literature, which he is often diametrically opposed to (notably, Murakami has almost no time for the Japanese literary press, and is quite opposed to the “guild system” that rules over most Japanese literature.)

Much is often made of how “western” Murakami is, and there’s no doubt that he is much more international than most other Japanese writers. However, while he is certainly in conversation with both Japanese and world literature, I think that considering the haecceity of his writing is a valuable thing; after all, I don’t believe that one could understand Borges by reducing him to a purely Argentine writer, no matter how important Argentina is to his writing, and (frankly) I think that’s probably the closest comparison to Murakami one is likely to find. Strecher comes to (I feel) a similar conclusion in a somewhat roundabout way, abandoning direct comparisons to other authors and focusing on the forms present in Murakami’s own writing – the individual psyche, the collective soul represented by the “other world” (a lingering question – is the “other world” persistent through all of Murakami’s fiction, or is it recurring figure? Is it the same other world, or the same kind of thing? Strecher argues, somewhat convincingly, for the former, while I had always thought the latter.)

If you’re in the mood for literary criticism, and are a fan of Haruki Murakami (or just one of those two things, but strongly,) then this is a book I would strongly recommend.

The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe by Matthew Gabriele and David M. Perry

Gabriele and Perry seek to reshape the story of the middle ages, changing it from a dark and brutal “dark ages” to something bright and strange. The authors emphasize continuity over discontinuity: instead of focusing what is lost from the ancient period, they point to what lingered and what remained, opening with a description of the construction of the ceiling of the Galla Placidia Chapel in Ravenna, and contextualizes it in the transition from the Roman period to the middle ages.

The middle ages are a fascinating time period and this book is a great treatment of it, which covers more than just the European Middle Ages, because the period was a cosmopolitan one, and the authors explicitly are not interested in ceding that ground to a regressive world view. I learned a number of fascinating things – most of them about the Mongol Empire and the presence of Nestorian Christians within it, honestly – but it was simply an easy, engaging read on a subject I enjoy. Highly recommended.

Doom Patrol, vol 5: Magic Bus and vol 6: Planet Love by Grant Morrison

(Volumes 1-4 reviewed here)

Shortly after it was announced (erroneously) that HBO Max’s Doom Patrol series was canceled, I managed to find the fifth volume of the series at Half Price Books. I took it as a sign, picked it up and read through the last two (we’ve had #6 for a time, but I didn’t approach it. The series might only have a loose continuity, but it has continuity, damn it.)

While I was already familiar with the Candlemaker sequence in #5, and broadly aware of the twists in #6, the whole plotline felt more fresh and well thought-out than I anticipated it would, especially with missteps from earlier in the series (the “Shadowy Mister Evans” bit felt like Alan Moore in his more self-indulgent modes, and I know that Grant Morrison will take a great deal of offense at that statement.)

Again, recommended.

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann

Much like The Bright Ages, I enjoy historical treatments of pre-columbian civilizations. While 1491 was very interested in – paradoxically – events that followed 1491, this is simply because those are the records we have access to, and this drops off after the first third of the book. Mann’s project here is to clarify a number of misconceptions that have cropped up over the years, and making it clear that Native Americans have been in this hemisphere longer than people tend to think and have had a greater and deeper effect than most people think.

Mann makes it clear that the pre-Columbian civilizations were not primitive: they simply had less opportunity to borrow from their neighbors and collectively benefit from invention (the oft mentioned North-South orientation of the Americas, as opposed to the East-West vastness of Eurasia.) As such, it is remarkable that not one, but two, separate neolithic revolutions happened here: one in the Andes, one in Central America – there is a vanishingly small chance that the two emerged from the same cultural root-stock.

As a result of this, there is a remarkable amount of variation between native American cultures, and what could have been learned from them could no doubt fill a library. A fascinating, if somewhat mournful, little book. Recommended.

What Moves the Dead by T. Kingfisher

(Reviewed by Edgar here)

While I much prefer The Hollow Places and The Twisted Ones (both previously reviewed by both Edgar and I here), I felt that What Moves the Dead is a fun little diversion. A variation on “The Fall of the House of Usher” as those were of The Willows and The White People, What Moves the Dead is borderline secondary world, taking place in a little-known (fake) Eastern European country, and following an individual whose gender is “soldier” as they go to visit their old friends the Ushers.

What follows is a sort of demythification of “The Fall of the House of Usher”: the gothic supernatural elements are given the veneer of science, though remain highly implausible. Of course, it’s still gothic, so it hardly matters that it’s implausible. Plausibility isn’t the point. The point is that something horrible and unsettling is presented and the implications are borne out to the end.

A solid work, though, honestly, my third favorite of the three works I’ve read by Kingfisher.

Tokyo Ueno Station by Miri Yu (trans. Morgan Giles)

A strange, mournful little novella narrated by a ghost haunting Ueno station, in Tokyo. This ghost was once a migrant worker, internally displaced to seek work to send money back to his family: his time in Tokyo was spent far from his family, and in the brief moments where his life intersected with theirs, he played the role of the dutiful son, husband, and father – but the demands of making a living in occupied Japan meant that he wasn’t able to be there terribly often. The sense given is that the longest time he spent with his wife before he reached the age of retirement was at the funeral for his son.

I honestly expected this one to be stranger? More... ghost-like, I suppose? However, the ghostly quality of the story reflects the social quality of something greater than mere invisibility for the narrator: to those around him, he is not simply invisible, not simply dead, but it is almost as if he doesn’t exist at all. He is a man who passed through his life with such a light step that it may as well have been a life un-lived.

I could see people getting some mileage out of it, but it’s possible that the pitch for it needed to be reworked.

84k by Claire North

“Blessed is her name, blessed are her hands upon the water, blessed is she the mother who gives life to the children in the mist, blessed are her hidden ways. Let the bars be broken let the journey end there is nothing at the end except darkness and the quiet place where all things fade amen."

One of the two real stand-out works of fiction that I read during this period, a work I attempted to read on Kindle a long time back, and which I recall Cory Doctorow describing as “exterminationist” during a reading. 84k is a dystopian novel, set in a future Great Britain. All of the people depicted were awful and unpleasant and deeply concerned with matters of class and propriety: I felt, while reading it, as if I was actually in Great Britain.

All jokes aside, 84k tells the story of a man who is not named Theo Miller, who lives in a society where all crime is punished by fines. He is, in fact, one of the assessors who judges the magnitude of the fines. Those who cannot pay are sent off to the “patty line” – forced labor to pay off the debt to society.

The man who is not Theo Miller, in presenting himself as someone by the name of Theo Miller, has no doubt incurred some kind of debt, and feels nothing but a spike of terror when a woman who knows him from his youth, Dani Cumali, spots him at a corporate retreat – he, on the side of the clients, and her, a member of the waitstaff.

A tense, delightfully claustrophobic story kicks off there, that unexpectedly opens up to one with broader, and much deeper implications.

In the House in the Dark of the Woods by Laird Hunt

Despite being incredibly short, this took me a great deal of time to get through, and didn’t really pick up until about the halfway point, when it stopped being a pastiche and started being its own thing.

A demure young woman, a wife and mother in colonial America, strays from the path in the woods, and is abducted into a fairy tale of swapping identities and changing forms. The opening really makes it all clear: “Once upon a time there was and there wasn’t a woman who went to the woods …”

It feels very much like a takeoff on The Vvitch, Robert Egger’s 2015 film, though that’s most likely the colonial setting and the cultural impact of that film, rather than any extended correspondence between the plot, which was only barely within spitting distance of the film.

Hunt’s book was more solid in the back half than in the front half, and while I was reading it I enjoyed it, but it didn’t grab me hard enough to make me burn through it in an afternoon.

Red Country by Joe Abercrombie

Joe Abercrombie’s take on a western, a la The Searchers, with a familiar face filling in for John Wayne’s character. Yet more delightful world-building and tightly plotted work from one of the better writers of Low Fantasy still working (I realize that most people prefer George R.R. Martin, and Martin is quite good – but I’m going to point to Abercrombie as my favorite.)

This book was good, but suffered a bit from being a pastiche of a story that is often used as the grounding for a pastiche. I felt a fair amount of déjà vu when going through this book – to the point where I wondered if I had read it before and simply forgotten – but then realized that it drew from The Searchers, and while I’ve never actually sat down and watched that film, I understand that it’s a classic, and one often used as inspiration: for example, for Brian Jacques’s sequel to Redwall, Matimeo, which I remember reading back in second or third grade. Thus, while I hadn’t read Red Country before, the broad strokes of it were familiar because I read through the version that centered on mice and badgers.

It wasn’t my favorite of Abercrombie’s books – outside of The First Law trilogy, starting with The Blade Itself, I think that The Heroes (reviewed in my last batch) might be better.

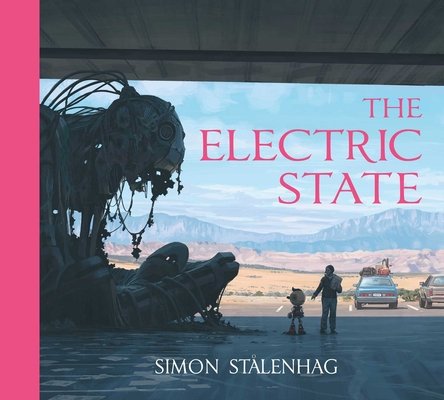

The Electric State by Simon Stålenhag

The sequel to Tales from the Loop and Things from the Flood (reviewed here), The Electric State takes place in a post-apocalyptic America, as more and more people plug into virtual reality and allow themselves to wither away, submerged in a sea of virtual consciousness.

The story follows a young woman and an oddly childish robot as they cross the fictitious state of Pacifica (read: California) looking for someone. The art is gorgeous and monumental, the implications are horrific. Highly recommended, though I think you should read the first two before approaching this, to get a sense for the fantastical alternate history that Stålenhag is building.

The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern

(Reviewed by Edgar twice.)

My enjoyment of this, I feel, falls between the two times Edgar read this. I listened to it in audio format, and while it was fairly enjoyable, there was a certain lack to the story that struck me as most akin to an itch between the shoulder blades.

Who, exactly, is the villain, if there is one? What, exactly, are the stakes?

It’s a fun little romp in places; it has a nice, winding sort of approach to the story and a lot of miniature asides that turned out to loop back in. On the smallest and middle levels of the story it very much worked, but on the highest level it stumbled a bit.

This is not to say that I disliked the ending, though, I actually did – towards the end, it took on a character very similar to Kentucky Route Zero, wandering around a chthonic otherworld through ruins that never saw the sun but, you know, not in a Lovecraftian way – I’m more dissatisfied with how the whole mechanism of the story was assembled.

Also, I was kind of hoping for monstrosity somewhere in there. It felt like there should have been some, and I was left wanting. I gave it 3/5 on Goodreads, and that felt too low, though 4/5 felt somewhat too high. Make of that decision what you will.

Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin

(Reviewed by Edgar here.)

The other fiction stand-out. I’ve had more experience with some of Felker-Martin’s earlier work, largely criticism, but this was the first professionally-published fiction I’ve read from her.

Early on in reading Manhunt, I felt somewhat alienated: here was a world that had no space for me. Even in comparable literature – say, the comic book Y: The Last Man, there was at least one male character for me to look at and identify with. However, I quickly realized (around the time the protagonists took a potshot at a group of crossbow-wielding TERFs) that my reaction to it was, at best, a little silly. After all, I remember dropping Terry Brooks’s The Sword of Shannara in high school because there were no significantly-developed female characters in the portion I had read through – what I was experiencing, the lack of someone to identify with, was something that both cisgender women and transgender individuals have had to deal with in relation to most fiction in the history of published literature.

So, I sucked it up and read through it, and it was a very well-drawn apocalypse. Beautiful nature writing sat cheek-by-jowl with strong plotting and well-developed characters, all traumatized to hell and back by the situation they were in. Most post-apocalyptic stories tend, I feel, to forget to acknowledge the foundation of tragedy that they rest upon, but Felker-Martin manages to weave that tragedy into every chapter: the alienation of the trans women who the story follows, the pre-apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic horrors all of the characters have survived, and the – to me – unique poetics of scab-picking that runs through the whole thing.

Highly recommended.

Remina by Junji Ito. (No bookshop link)

Best thought of as – essentially – a David Cronenberg-esque take on Melancholia. An astronomer discovers a planet emerging from a wormhole, transported here from another universe, and determines that it did so sixteen years ago, on the same day that his daughter was born. As such, he names the new planet “Remina,” after his daughter.

Shortly afterward, because this is a Junji Ito story, the planet begins to race towards Earth at the speed of light (or more, it’s unclear) and annihilate every celestial body in its path. The young girl, innocent save for the fact that she shares a name with the mysterious planet is first feted as a celebrity (in that fashion that idols often are in Japan; there’s something similar to celebrity but difficult for me to parse about the whole business. Cultural differences, I suppose) and then the target of cultish assassination attempts.

As the world descends into chaos, the intimation that the approaching planet is alive grows ever stronger. However, this is a Junji Ito story, and those familiar with the man’s work will tell you that rarely is there a happy ending to be found.

Ito is, apparently, a very well-adjusted man and very personable, but his authorial outlook tends towards the bleak and grotesque. The most likely explanation for what is going on here is not that there is some mystic connection between Remina the girl and Remina the planet, but that it’s simply a fateful accident that the planet was given that name. The universe that Ito depicts is, quite often, one that has little concern for human sense-making: horrifying events don’t happen to cement a moral lesson, they just kind of occur because.

Recommended, if you can get your hands on it, though it is a fairly brief read.

The Nightmare Stacks by Charles Stross (Laundry Files #7)

I’m clearly not waiting to review all of these at once, but do not expect me to write a review until completing The Labyrinth Index (#9) and possibly not until I’ve completed all remaining volumes up until Quantum of Nightmares (#11.)

I love these books, and the titles are very fitting, but I also feel ridiculous writing them all out.

A Little Hatred by Joe Abercrombie (Age of Madness #1)

Will be reviewed alongside the other two volumes in the trilogy – The Trouble with Peace and The Wisdom of Crowds – at a future date.

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we reviewed here (so long as you’re in the United States.)