Personalizing the Impersonal: on Hyperobjects, etc.

The trailer had me rapt, swept up and disturbed on a subcutaneous level as only my first time or two listening to Salem had managed before. The jaunty tunes, the breathing, the distorted voice and the floating dolls and the visual debris of video: In this house, the voice intones, the sentence unfinished, the carpeted stairs leading into yet more crawling darkness.

The poster for Skinamarink, which certainly captures the vibe.

I was, admittedly, primed to like Skinamarink. I had first heard about it via an effusive tweet from Gretchen Felker-Martin, and I take her recommendations seriously; when I saw the trailer at the beginning of Violent Night (a movie I saw in an actual theatre on 28 December, which was neither the time nor the place for it), I knew I had to see it. Finally, I was able to, on a Tuesday at the Screenland Armour with a friend (who also has a blog, and reviewed the movie here). For just about 100 minutes, I peered into the visual static of video footage (though the film was shot digitally, proving Eno’s point about media) and entered into the terrible dream that Kyle Edward Ball created for very little money but to incredible effect.

The film manages a feat of which I am not sure I am capable, but which never fails to win me over: every formal technique available to the artist is marshaled to serve the fiction; by dint of incredible sound engineering, extraordinary use of focus and lighting, and even the deployment of sub- and intertitles, the viewer is plunged into a child’s nightmare. There is no scene in the film that I couldn’t imagine a child waking up crying about.

Now, it’s possible that I’m just the target demographic, in that I spent some nightmare-ridden and/or insomniac nights in recently-built, fully-carpeted suburban or exurban homes in the early 1990s. But the film does, very efficiently, create a sonic and visual language – a feat Cameron has discussed elsewhere – and expect the viewer to keep up. In so doing, however, it plumbs the depths of the dissolution of self, culminating in young Kevin’s plea for relief or embrace as he asks the writhing darkness who it is.

This is, of course, the horror of the film: the total immersion in this tormenting, tormented darkness, the longest night of your life from which you emerge utterly different than when you began it. Where Ball sees horror, however, others have seen something else.

※

I was chatting with a coworker, and somehow we got onto the topic of hyperobjects. We agreed to do an informal read-a-long, and so at some point this past month, I picked up Timothy Morton’s book-length exploration of the topic and dived in.

The nature of work and schedules is such that this coworker and I didn’t have much time to meaningfully discuss the book beyond surface critiques. He didn’t like Morton’s reliance on pop cultural comparisons; I am still not totally sure what “object-oriented ontology” is, beyond knowing what each of those words means: both of us ended up turning the corner on these critiques by the end of the book, and it ended up being a very rewarding experience. I suspect we’ll be “Oh, and what about –” with it for a while.

But part of Morton’s point about hyperobjects, and objects in general, is their identities, their natures as objects for themselves. Working in the framework of object-oriented ontology – though usually preferring the charming acronym OOO – Morton explores such objects’ “being-for” themselves. A hyperobject is, Morton says, viscous and phasing, non-local and temporally undulating: it gets everywhere, and its influence extends forward and backward in time, and you can’t point to any one iteration of it and say, “This! This is the thing!” (Examples include radiation, global warming, and the internet.)

But as Morton explores this, it becomes increasingly clear that what we are exploring is not a something-else but a something of which we, of which I and you and Cameron in the kitchen, are already a part. Something else is going on.

※

The WTNV tweet in question, positioned as a kind of inspirational image.

Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy takes up various positions around Area X, a zone in the Stalker sense where nature runs rampant – awry from a human perspective, but clearly doing something in its own right. Cameron and I have both discussed them elsewhere, but they are, essentially, book-length explorations of the classic Welcome to Night Vale Tweet, “NATURE FACTS: Nature will kill you and then make new things from you.”

Needless to say, this is typically met with more than a measure of terror – but not from all parties. The Biologist is the example most in focus, but other characters, especially the Psychologist, Whitby, and the man who would become the Crawler, see in the writhing endless verdance of Area X a promise, a kind of home or a way of being that they intuit as something beyond their individual selves, abyssal in the sense of both depth and height, and gazing back as surely as they gaze or seek to gaze upon it.

What is promised by Area X? What does Whitby, for example, see in it? Perhaps more materially, what does it see in Whitby?

None of these is the right question.

※

It was always going to come back to language, to the fundamental shortfalls of tongue and teeth and tentative scribblings in the vast dark of the world. We all know, of course, that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is too strongly interpreted, leading to dumbfuck articles about like, “Did you know that the ancient Greeks couldn’t see blue!!!!” That’s not true – but language does make blinders for us, and channel our thoughts in ways that aren’t necessarily visible until thrust into the light. (Hell, reading this piece about Pamela Paul and what its author terms her “rogue we” has me a bit self-conscious about that last sentence, even.)

And of course, I’m about to start talking about pronouns.

In English, we have a number of singular pronouns. I, you (or thee, more properly, but who gives a shit), he, she, it, they, a cavalcade of neopronouns. Pronouns are, of course, used to refer to someone or something without the awkwardness of constantly using proper nouns – a fact necessitated by the relative lack of inflection in the language. But in using these pronouns, we also draw distinctions between people: where I end, you or he begins; where they aren’t, thou art.

But what if, on a very basic level, these distinctions were meaningless? And further, what if finding a way to live with that, with ourselves in and of that, were imperative? And more practically: what do you call that?

※

I had my qualms with the film adaptation of Annhiliation, but this image really Got It, whatever “it” is in this context.

One of the several horrors is subsumption: consumed and assimilated but still, on some level, you. This is especially on display in the fates of the Crawler and the Biologist in the Southern Reach trilogy: both are transformed by and made part of Area X, but apparently retain some kind of personhood, some sense of a self ablated and displayed and folded back in, as if pair of cosmic hands, folded together, opened to show a glimpse of a person that was also an emergent property of the hands themselves.

Or consider: Skinamarink works in part because it makes you, the viewer, party to its action. It is you who experiences what Kevin experiences, you who is also watching Kevin and Kaylee. In this way, it operates very much as the work of art from a cosmic horror story, but the horror story is that you can dream dreams, and sometimes they’re like that.

I’d say I run the risk of stating the obvious, but there’s no risk involved: these are presented as horrific outcomes. This is the worst thing that can happen to you, because when it happens, there is no more “you,” not in any meaningful sense. As an individual living in a world after Kant, a world in which “we” is assumed to be made up many individuals all doing whatever the hell they want, acting as if they act alone, this is the greatest conceivable horror.

But Skinamarink is not the Borg, and neither is Area X. They’re something different. They are nonhuman agents, approaching personhood but not like that, a monumental-horror figure that gazes back – not as the abyss does, but from eyes you can gaze back into because they are the eyes of your friend or lover or coworker. They operate using the logic of the hyperobject – and if it seems like a reach, it’s worth noting again that Morton includes My Bloody Valentine’s guitar sounds as an example of something that works like a hyperobject.

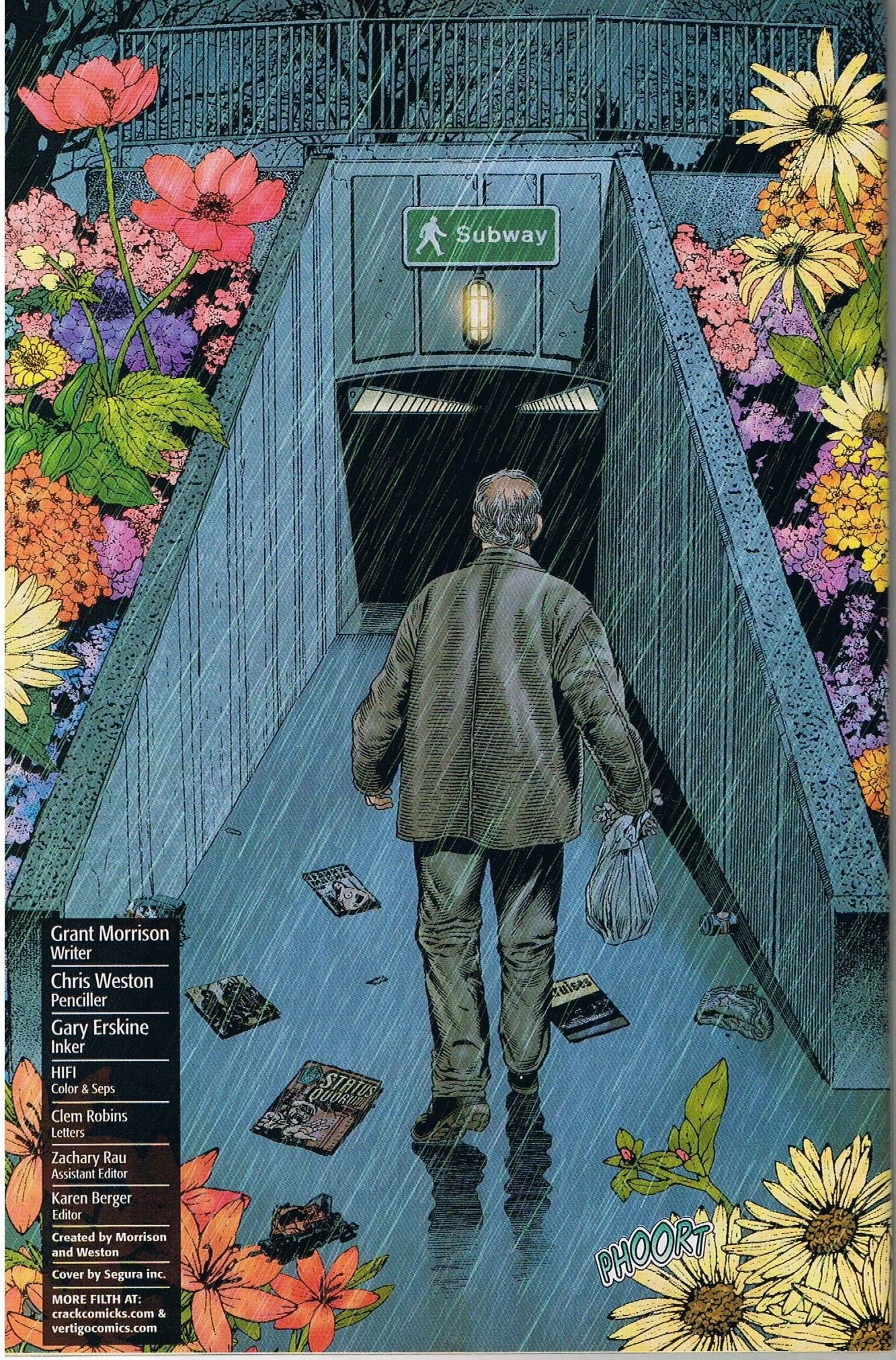

So now the question is, can there be a non-horrific outcome? Morton, I think, suggests that we can interact with hyperobjects in a meaningful way, in which some kind of self remains as a useful construction. For a pop-cultural example, I might put forward the ending of Grant Morrison’s The Filth, in which – spoilers for a twenty-year-old comic, I guess – Greg Feely, the disaffected main character, attains a sense of purpose and fulfillment in life by accepting and joining in the oneness of things, using the abilities this brings him to make the world better, in whatever small ways he can. The obvious counterargument, of course, is that Feely is clearly viewed as insane by “normal people” – to which I offer, (1) who gives a shit? and (2) do you really want to be Glaucon in this Republic, bitching because you can’t have treats?

※

I’ve been dancing around the pronoun question in this piece, but let us consider the closest we’ve got to a proper impersonal pronoun: the classic, oft-scorned “one.” “One oughn’t,” I might say, putting on a posh accent, before doing exactly whatever I described. “One scarcely knows,” murmurs a character in a British novel of a certain vintage. It has a certain tone and a certain connotation in contemporary diction – which is unfortunate, because I think it might be useful here.

Consider: the impersonal is rarely actually impersonal. More often than not, it forms a polite mask for an imperative, or a shield for a first person singular admission. And even when it is truly impersonal, it marks a kind of aspiration about how people should behave.

The final panel of The Filth, an image I found via this thoughtful review of the whole affair.

What I’m getting at here is that there are ways for us to talk about these things: about hyperobjects, about the world as characterized by Deleuzo-Guattarian rhizomes or Viveiros de Castro’s explication of Amazonian perspectivism, about a becoming-part-of that entails constant, simultaneous dissolution and regeneration. If we take this “impersonal” construction as a way of thinking into these concepts, it offers the possibility of greater understanding.

If one – you, me, the Biologist, Kevin, Greg Feely – is or becomes part of a greater one, the impersonal construction can then be read and used as a way of thinking about what has happened, the grammatical and ontological feat accomplished. When the distinctions between persons collapse and the living, writhing network of things becomes apparent, what can we do but slide from the “we,” the “I,” the “you” – all clusive, all positioned by their very nature to indicate “this” and thereby necessitating “not-this” – into a “one” that speaks as it hears, that sees as it is seen, that is, essentially, the Fisherian eerie writ large.

For whether by failure of presence or failure of absence – we haven’t really had a winter here (an absence) and I cannot stop thinking about global warming (a presence, breathing on the back of my neck) – Morton’s hyperobjects surround us. But if, to steal one from LeGuin, the word for world is forest, surely it is the forest whence comes Viveiros de Castro’s “cannibal metaphysics,” a worldview that presumes a soul in every thing. After all, in this view, all of nature is human, but has become trapped in other forms and wants to be human again.

While Skinamarink offers this becoming-one as an unequivocal horror and the Southern Reach as a source of ambivalence, it’s nonetheless useful to consider The Filth – to consider these works as a way into the hyperobject concept. Useful, too, is the concept itself, which Morton is at pains to clarify. As readers and viewers – and even moreso as artists – it behooves us to engage in these considerations. Or, you know: one ought.

※

Follow me and Cameron on Twitter, if you want; you can also preorder an anthology I’m in here.