Cameron’s Book Round-Up, May and June 2023

Okay, as usual, I let this sit too long. In my defense, I had a new job, COVID, and international travel in there, so things got dicey. A lot of good books this time, though it covers more ground than I normally do, time-wise. All title links go to bookshop.

It by Stephen King.

(Mentioned in my Unbureaucratic Fiction reading guide.)

There’s not much I can say about Stephen King’s It that hasn’t been said many times previously. It is a massive book – the audio book, which I listened to, was 45 hours in length, and it is a brick of maximalist Americana horror fiction.

My experience of the original is actually the third version that I’ve encountered. I’ve previously seen the 1990 version with Tim Curry as Pennywise the Dancing Clown, experienced on a gauntlet of rented VHS tapes in my friend Sean’s basement over a long weekend; I also watched the duology, with Bill Skarsgård in the title role, in a group put together by prior contributor Joel Gilmore. Apparently, though, there was a Hindi-language adaptation called Woh in 1998 that spanned a 52-episode series. I haven’t seen that one.

The thing that interested me most was the restructuring that both adaptations engaged in: they split the story into a child section and an adult section. This makes sense from a filmic perspective, though from a writing perspective I’m glad that this isn’t the case: the adult section encircles and contains the child section, with the reunions in the Chinese restaurant and library serving as a vehicle for compiling the rather extensive child narrative. The two sections being intercut like this change the experience of it: it becomes not a record of childhood but a dream of childhood. Given the potence of nostalgia as a theme within the work, this supercharges the text.

The podcast Wyrd_Signal, which regularly goes on unannounced hiatuses and suspends its patreon (which, frustratingly, seems to delete the patreon episodes entirely, making them lost media), had an interesting take on Stephen King’s work in the middle of their discussion of Rob Zombie on the last available episode. They’re not the most original in this, and I think Horror Vanguard touched upon it as well from the other end, but Stephen King’s works are almost as much about Americana as they are about horror. He’s the Norman Rockwell of horror, and while I’ve read a few Stephen King novels recently, I have to say that this energy is the strongest in It.

Derry, Maine, is portrayed as a sick and awful place, but it is a sketch of America. The novel seems to think that this may be something that can be consigned to the “bad old days”, but it isn’t nostalgia: it’s analysis. America in 2023 has a close resemblance to the Derry of the 1950s discussed in detail in the book: the only difference is that we have yet to do anything about the clown(s) responsible.

The World We Make by N.K. Jemisin.

(Sequel to The City We Became, reviewed here and here.)

Perhaps I should put together a reading guide for “contemporary fantasy novels about gentrification” – this book, its predecessor, and Sam Miller’s The Blade Between could all land on there, and Edgar’s been talking about another one.

Apologies to Mr. Miller, but Jemisin is currently the best writer on that list, though I will comment that The World We Make – by necessity – is a somewhat weaker book than its predecessor. Part of this is my own predilection: I had that whole guide to fiction that eschews organizational politics, and while those were present in The City We Became to a small extent, they’re a much bigger part in The World We Make. The central characters, avatars of great cities, are part of a community that must work together and confront a threat – and the final showdown is great. The political wrangling involved in making this happen just didn’t seem to work for me.

The story focuses on the seven avatars of New York – one for the city as a whole and one for each borough (and Jersey City.) They are threatened by an entity that is a predator on cities, the Cannibal Metropolis of R’lyeh, hovering invisibly (to mortal humans) over Staten Island, vampirizing it of its essence. To fight this monster from the Ur-verse, they approach and attempt to recruit elder cities to assist them: Paris, London, Istanbul, Tokyo, and others.

On a more granular level, it also follows the travails of the individual avatars as they try to find their feet after their awakening.

The character work in this one is a bit weaker, and the human-level conflicts are less well-drawn than the previous volume. There are clear references to recent events baked in: the truck caravans of Trump supporters that drove around cities (and in at least two cases tried to run over friends of mine) make an appearance and are driven off in a sequence that feels like wish fulfillment (it’s a wish that I certainly shared, but it feels dated already.) So I have some issues with it.

I still consider this book to be essential reading, though: The City We Became is a beautiful novel, and this is the conclusion to that story. I might wish it extended further, I might wish that there were more of it, but this is what we have, so if you loved the first one, I’d recommend reading it.

Just Like Home by Sarah Gailey.

(Reviewed by Edgar here.)

A clear example of a “Woman-in-House” novel. Vera Crowder is called back to the house her mother threw her out of when she came of age, the house built by her father, the serial killer. She finds her mother occupying a rented hospital bed in the dining room, and an artist – a vulgar man whose own father was the biographer of Vera’s father, Frances – living in the shed in the back yard, acting as handyman for the bed-bound owner of the house.

It’s a fairly typical example of the genre, and the first one I read after assembling the reading guide and analysis of the story. As such, the beats seemed to come at fairly standard places, though the supernatural elements were not signaled quite as early as I think would have benefited this book as a whole.

Despite this, it’s a very competently assembled example of the genre, and simply because it follows a recognizable myth-structure doesn’t mean that it isn’t worth reading. I still sometimes hunger for extremely paint-by-numbers airport fantasy and space opera, because it works as a kind of comfort food. If what I refer to as “woman-in-house” stories are that for you, Just Like Home would be a real treat for you.

Babbling Corpse: Vaporwave and the Commodification of Ghosts by Grafton Tanner.

(A reread, previously discussed here.)

I’ve been preparing for a (now, sadly, delayed) game of the Public Access RPG from the Gauntlet, and some of my reading choices have been motivated by that. It’s a game about nostalgia, and Grafton Tanner writes beautifully about both personal and collective nostalgia. I still need to finish The Hours Have Lost Their Clock, and I thought about taking it with us when we were traveling, but I had an ebook of Babbling Corpse, so I simply reread that.

Perhaps it is simply getting into the habit of reading such theoretical works, but it felt thinner this time around than the last time. Perhaps, also, it is simply the fact that I have read it before. It remains a good read, and Tanner’s research is exceptionally strong. I am in the process of raiding his bibliography, which is one of the best things I can say about it this time around. A big part of that is that I already fully accept his analysis of Vaporwave, though Vaporwave itself is coming up on ten years old, now, which is ancient by microgenre standards. Of course, it’s sister and daughter genres are still proliferating, and its aesthetics have broken containment (see my review of the video game Paradise Killer here for more on that.)

This Book is Full of Spiders by Jason Pargin.

I greatly enjoyed John Dies At the End, though the followup takes things in a direction I didn’t really care for (not enough that I would drop the series, mind you, and taken on its own it was quite well done.) This is a zombie apocalypse novel that hates the idea of zombie apocalypses. It does not hinge upon a virus or black magic (necessarily), but on an interdimensional parasite, a spider-like creature that eats and replaces the tongue of its victims, sinking tendrils into their flesh. Pargin quite hauntingly has the narrator then tell you that you should be aware, now, that your jaw has weight and requires effort to keep in place.

And, honestly, the narrator is the real draw of this book and those like it: there is a whole theory of narration here that I want to dissect and analyze, because everything is filtered through the persona of Pargin’s former pseudonym, David Wong, which he also wrote under for the website Cracked.com. Wong is not simply an unreliable narrator, Wong is up front about being an unreliable narrator. Pargin will have the character tell you at the end of the story that a whole character was completely different the entire story and demanded to be made cool – and, having done that, Pargin will banish the character from the narrative with mockery.

Of course, by this point, the story is over, and the story is the same, though the story also includes an admission that the story is a partial fabrication. It’s a fairly unique metafictional move that serves to make the horror comedy angle of the story work. We are left with the implication that the events, which are unseen, are horribly traumatic and gut-churning, but the story created from these events is stitched together by this clown that doesn’t care about being accurate or fair to the characters. He has his own perspective, he tells you what that perspective is, and leaves it to you to subtract the perspective from the story to get at something like the events. But the events are inaccessible (partially due to being, to us, of course, fictional) because he’s already ripped out certain portions of it. Does he care? Not in the least.

I think that this technique, at least, is fascinating, though the story itself didn’t really work for me quite as well.

No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai

From one weird guy to another. No Longer Human is an existentialist novel from Japan, published in 1948, one month after the author’s suicide and boy can you feel it. The title – in Japanese, Ningen Shikkaku, properly translated as “disqualified from humanity” but sometimes retitled “a shameful life” – follows a strange young man who does not, in the least, understand human behavior. He is born to a wealthy family, acts a class clown in his youth, grows into a decadent failed artist in his youth and degenerates further and further from there, exploiting and being exploited in turn, all the while claiming that he doesn’t understand human behavior.

It is a fairly standard – and classic – work of existential fiction, much of which seems to hinge on presenting a strange character, constructed in the negative: this person doesn’t conceive of themselves as being superlative to the norm, they view themselves as being deficient from the norm. Compare the central character of his book – Yōzō Ōba – to Camus’s Meursault or Jean-Baptiste Clamence, or to Dostoevsky’s Underground Man. They conceive of themselves as characterized in the negative: their identity hinges on what is not the case about them. Perhaps this is accompanied by a belief in their own superiority for other reasons, but it is a lack that characterizes them. In this case, Osamu Dazai identified that fact zeroed in on it, and portrayed it excellently.

I don’t want to diagnose fictitious characters, but I’d love to see an analysis of this character from a critic who really understands autism and similar conditions.

Dracula by Bram Stoker

I can honestly say less about Dracula than about It. There’s a certain point in the life cycle of a horror story, where it becomes well known enough that it begins to flip around into comedy: our minds simply begin supplying punchlines, because the suspense is defanged. This process is happening in real time with the work of H.P. Lovecraft (you can’t have plushies of the monster on the market and have it be still horrifying, I would argue.) You can encounter “my good friend, Count Dracula”, but you can’t keep a straight face about it.

Still, if you take the time to try to occupy a victorian frame of mind, it becomes an obscure and horrifying story. This is partially aided by the fact that there has never been an accurate adaptation of the story. Every version of it simplifies it and tries to wedge it into a modern framework, and this makes it easier to encounter the original.

Take for example what Tumblr has taken to calling the “polycule” from Dracula – the grouping of Dr. John Seward, the cowboy Quincy Jones, and Lord Arthur Holmwood, who all proposed to Lucy Westenra on the same day. These characters are often combined and simplified, while in the novel they form what can only be thought of as a Dungeons and Dragons style adventuring party with Jonathan and Mina Harker and Dr. Van Hellsing, hunting the count. They form a conspiracy with the intention of annihilating the evil, bound together by a shared tragedy. This angle is often elided, alongside Jonathan’s fondness for the kukri that he picks up later on.

In short, what begins as a horror story finishes as an adventure story, and while I understand the editing that goes into it, it becomes quite jarring. Personally, I’m not convinced that Bram Stoker is necessarily that good of an author, but it was quite the ride.

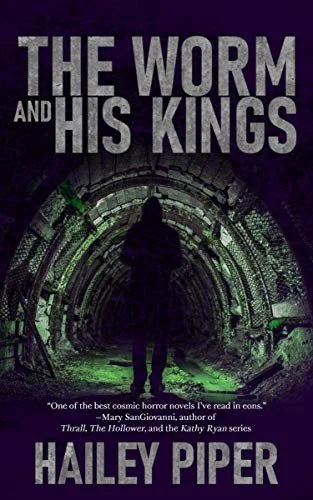

The Worm and His Kings by Hailey Piper

(Reviewed by Edgar here.)

A book that puts the “cosmic” back in cosmic horror, this story takes place in New York in 1990, and deals with a homeless young woman – Monique – hunting for her missing girlfriend, Donna. Monique lives in a homeless encampment that is being stalked by a monster called “Gray Hill”, a towering figure that abducts women in the middle of the night.

She witnesses an abduction, and follows the monster to find out where it is taking women, convinced that it has taken Donna. Things get worse from there, rippling outward from this initial point.

What follows is a conspiracy involving missing people, a cult that worships the titular worm, and a rather...Bergsonian disaster of time.

A fascinating and compelling read; my only complain is that it was too short. I’ll need to track down the followup books, though I must admit to not really understanding how a followup to this story could exist, given the nature of its ending.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.

Also, Edgar has a short story in the anthology Bound In Flesh, you can read our announcement here, or buy the book here