Failing to Commit to the Bit: A Cardinal Sin in World Building

Hey, folks, short piece today. We’ve been without a refrigerator since late last Thursday and I, at least, have missed two days of work — necessitating that I go in on my day off so that I get something in my next paycheck. At least that means I had time to write my syllabi, but teaching won’t pay until almost a month from now.

As such, this piece is going to be somewhat abbreviated.

※

In the Disney Star Wars trilogy, Rian Johnson came in to do one movie and threw down a smoke bomb. The response was a course correction with many issues, and we can label them all refusing to commit to the bit. Read more about it here.

In both my last book round-up, and in Edgar’s, we both had books that failed to properly think through the implications of their world building. For me, it was the way that stacking works in Altered Carbon, for Edgar, it was a number of factors in T.J. Klune’s In The Lives of Puppets. Both of these books fell victim to what I tend to refer to as “failing to commit to the bit.” This is separate from having bad or scattershot world building — I tend to find that distracting, but a book can still be good and have a setting with nonsensical elements (hello, Baru Cormorant series — look at a map for those books and tell me that plate tectonics will do that) — it is, instead walking right up to what should be a major component of the setting and then deciding that we don’t want to deal with that.

This isn’t necessarily a one-note sort of thing. World builders can diverge from reality quite a bit, and for fantastical stories, this is compulsory, whether something as restrained as Hav by Jan Morris or as outre and surreal as the work of Leonora Carrington. However, not all divergences from reality are created equal, and they should all be to roughly the same degree in the same work — most importantly, the writer should understand what the big asks from their work is and implies.

To be a “big ask” as I label it, what I mean is the overlap between two specific questions:

How central is this to the story?

How unfamiliar will this be to the reader?

If there is a significant degree to both answers, then the element needs to be explored and grounded to a certain extent. It doesn’t need to be perfect, but it needs to show that the writer in question has given thought and attention to this.

I haven’t watched this movie in a couple years, is that Rainn Wilson in the back?

Failure to do so tends to lead to one of two results: either the work failing or a preponderance of what is often called the “thermian argument” — referencing the well-meaning aliens from the film Galaxy Quest, who abduct the cast of a Star Trek analogue show to help save them because they lack a conception of the difference between fiction and reality — where the only defense of a particular text and the choices that were made in its creation are marshaled from the text itself (or para-textual elements, such as a comic book released alongside a film) without consideration. Which means it either doesn’t land at all or spontaneously generates one of the worst parts of so-called “nerd culture.”

That is — responding to a critique of a particular text as if that response indicates a deficit of knowledge about the text. To be consciously and intentionally engaged with a story (regardless of the medium) means, occasionally, saying “this is stupid” and stepping out of the headspace of accepting the universe presented as a totalizing whole: you walk away from Tlön so that you can see it from a higher vantage point and point out the gaps in the map.

Note: no one gave a shit about this in-universe. Or out-of-universe. But the in-universe part explains the out-of-universe part.

We’ve all seen examples of this. Off the top of my head, perhaps the highest profile one would be the inescapable mass media franchise of the Marvel Cinematic universe. In The Eternals, a movie that people actually paid money to see, the Earth was apparently an egg that began to hatch and give birth: a giant head, three hundred miles tall, emerges from the planet and everyone just sort of…moves on? It’s occasionally referenced, but there’s no indications that weather patterns shift or anything of the sort.

Meanwhile, the closest analog I can find that actually looks into this is in a tabletop RPG by Kenneth Hite, The Day After Ragnarok, which draws heavily from David Brin’s 1987 short story “Thor meets Captain America” (not an MCU property, despite the title.) In the backstory of this game, the Norse world-serpent, Jormungandr, is called into our reality near the end of World War II and begins to eat through the world like a worm through an apple, only to be killed when the trinity device is loaded onto a bomber and flown on a suicide mission into the snake’s eye. The 300-mile-wide snake being dead doesn’t “solve” the problem. Consider the map of Britain from the game:

Do you see the issue? Hint: the snake is part of the map.

A “world” is not simply a place where a story happens. A world is a connection of causal and correlative relationships. All of its parts are in tension with one another to the point where if you pluck one element out of place, it should have a cascading relationship across all of the components in place. If you’re not committing to the bit, you’re not creating a world. You are (badly) dressing a set for a drama that it really feels like you’re not interested in actually exploring.

I’m given to understand that there’s at least one other film critic that uses the same criteria as James, but one good turn deserves another.

You may note that at no point am I talking about “realism” here. We demand different degrees of verisimilitude from The Chronicles of Narnia, Star Trek, and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. It would be a mistake to hold them to the same standard, because — as our friend James Teller says over on his own website, If You Want the Gravy — you need to judge a work on what it’s attempting to do, not on some hypothetical objective standard. So let’s propose a third, two-part, question to sit above the other two, written out above: does the story communicate its desired degree of realism (i.e., congruence with observed reality) and does it live up to it?

Now, this doesn’t have to be solely about fantastical divergences from reality: one can easily look at stories that sit closer to consensus reality and try to see the bright, straight line from character motivation to behavior within the metaphorical proscenium arch of the story and ask does this make sense? For example, if a villain is motivated by a tragic backstory, how does that actually inform how they behave in the situation of the plot in question?

Fundamentally, this comes back around to what I think literature is for — something that I’m not sure I’ve ever explicitly laid out on this website — and that is to ask questions of the reader. These are not, in good literature, questions that have an explicit, already-decided-upon answer, they are open-ended questions that require meditation and contemplation to get through.

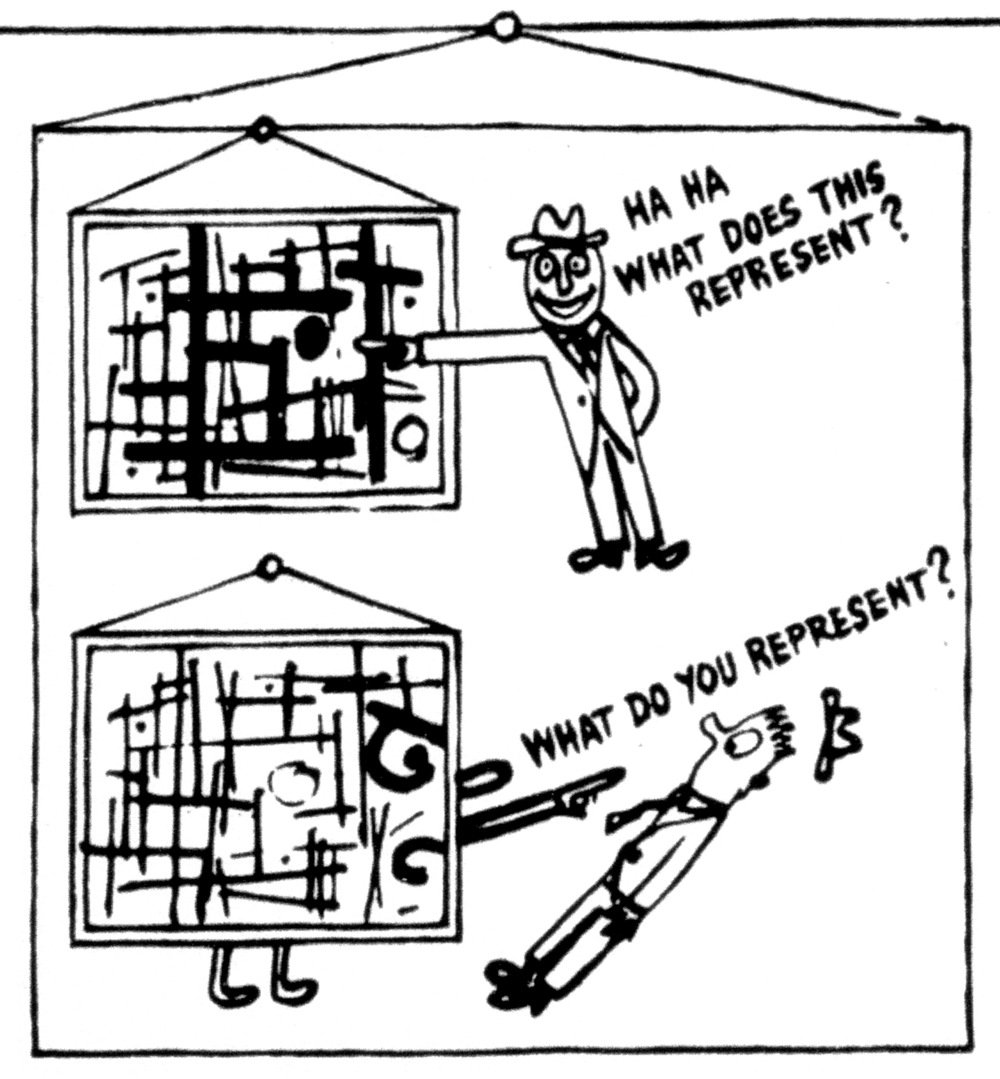

In this way, literature is very similar to abstract art as described by Ad Reinhardt in the classic instructional comic:

Which is followed up by a caption over an image of our friend the art criticism cowboy (depicted above) laid out as by a haymaker: “An abstract painting will react to you if you react to it. You get from it what you bring to it. It will meet you half way but no further. It is alive if you are. It represents something and so do you. YOU, SIR, ARE A SPACE, TOO.”

We could possibly make from this a new version about literature — not about space here, but about discourse. Perhaps that is getting a bit far afield, but it is true that stories will react to the reader if the reader reacts to them, and a big part of making sure that these reactions are productive is making sure not that the story is self-consistent, but making sure that the story isn’t abnegating itself in the process of telling.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates, and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.

Also, Edgar has a short story in the anthology Bound In Flesh, you can read our announcement here, or buy the book here.