Edgar's Book Round-Up, January-February 2020

Here are we, a few weeks into the ‘20s, and apparently my recently-learned practice of reading several books at the same time across several media has gotten me 10 deep already. I didn’t want to try to go through more than that all in one go, so we’re starting early on the book round-ups. While I finished a few more items after my final review of last year, none of them made much of an impression. So here we are.

I started the year off strong, finishing the audiobook version of Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone’s delightful novella, This Is How You Lose the Time War on New Year’s Day. The story follows two agents on opposing sides of the titular time war who, in the course of their activities, become aware of one another’s trademark moves and begin leaving notes to one another, gradually falling in love. Although brief, the novella is full of delightful set-pieces — one character meets with her boss, who is disguised as a soviet field medic in World War Two and is right in the middle of a battlefield amputation; a letter is described as being hidden inside the skin of a seal that the recipient kills and eats.

It’s good enough that I feel fine using a banner.

I can’t say I was surprised at how much I enjoyed this one; Amal El-Mohtar has been on my radar for years thanks to her absolutely phenomenal genre poetry (she published one of my poems once, which can still be read here), and the increasingly desperate and tenuous relationship between the central characters was richly felt. My sole qualm with the book was that, while I was personally delighted by the type and scope of the literary references embedded in the work, they sometimes felt less than necessary — showing off the authors’ knowledge bases, rather than amplifying the story — but I’ve forgiven far greater sins, and honestly, looking into Thomas Chatterton is scarcely a waste of time.

I love this cover art, too.

After that, I finished the second installment in Tamora Pierce’s The Circle Opens tetralogy, Street Magic, which I read through the Libby app on my phone. As per, I will hold off on a fuller analysis until my completion of the series; I must do the same for the next book I got through, The Black Tides of Heaven by J. Y. Yang, though in the case of that one I may only put it off until I finish its companion piece, The Red Threads of Fortune. I will confine myself to remarking that I thoroughly enjoyed it, and received it as a Christmas gift from Cameron, who, unsurprisingly, made an excellent choice.

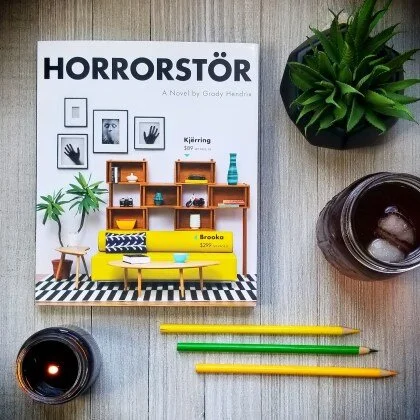

In any case, the next book I finished was another audiobook, also from Libby: Horrorstor by Grady Hendrix. Cameron wrote at some length on Horrorstor last year, and it was his recommendation that inclined me to it. The novel, which follows a handful of more or less hapless employees of Orsk, a store that is definitely not in any way modelled on Ikea, as they embark on an overnight shift to discover the source of a number of gross occurances in the store (feces on the product, and that sort of thing). Unfortunately for them, the store is actually super haunted, having been constructed on the site of a nineteenth century prison.

This lovely image comes from Samsara Parchment’s review.

I’ll generally cosign what Cameron had to say about the analogies Hendrix draws between carceral practices and contemporary retail. Hendrix’s prose was clear and the story well-constructed. My main beef with the novel, honestly, was Amy, the protagonist: while a well-rendered portrait, I’ve worked with Amy, and I can’t say I relished the experience, let alone reliving it for fun. Basil, the manager who orchestrates the overnight in the first place, is fundamentally a more interesting person to me, and there was definitely a point, when things looked pretty bad for him, when I considered setting the novel aside. Ruth Anne, too, was an excellent character study of another type I’ve worked with; when, at one point, she tells Amy to, “put on her big-girl pants,” I’m only lightly exaggerating when I say my spirit sang.

After escaping from Orsk, I finished Blake Butler’s Nothing: A Portrait of Insomnia, which I burned through very quickly both because Blake Butler is one of my favorite working prose stylists, and also a friend wanted to borrow it. While Nothing didn’t quite hit me as hard as There Is No Year, the novel of his that I read first, did, I am inclined to attribute that more to my biases on beginning the book than any particular flaw.

Not pictured: the fact that on my copy the (z)s glow in the dark.

Because, while Nothing can accurately be described as a work of creative nonfiction centering on insomnia, it’s neither memoir nor journalistic enterprise nor even whatever the genre is that let John Darnielle write a novella as a 33 1/3 entry. It is, rather, a combination of all of those, plus Butler’s electric style. One chapter began and ended with two magnificently long sentences, punctuated with footnotes that ranged from material to the topic to increasingly desperate iterations of the word “stop,” that perfectly imitated the pre-sleep gibbering that generally means you’re fucked for the night; at later points, he drifts into hallucinatory semi-autobiographical fictions involving a man in a car and the neighborhood you thought you knew transforming around you. Butler’s parents, with whom he was living during the writing of the book, also make appearances: Butler’s mother, as sleepless as he is; his father, increasingly ringed in by unfolding dementia. Foucault is referenced? And then there’s lines like this:

We are full of our blood, and we have hands.

What’s not to love?

I also read, partially through Libby and then, because I had money and was thoroughly enjoying it, in a hardcover copy I bought for myself along with the follow-up novel, Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows. As is perhaps obvious, this one really grabbed me; I had seen quite a bit of hype for it among various book bloggers, and they were absolutely justified. I will, however, restrain myself until I finish its sequel, Crooked Kingdom.

I discovered, towards the end of last year while slogging through one of the above-mentioned items that didn’t really grab me, that I enjoy listening to audiobooks at 1.25 times their recorded speed, which may account for how many of them I have burned through. But the next one was also an audiobook, also from Libby: Get In Trouble by Kelly Link.

Have another banner, this one from Tin House’s Between the Covers episode on the book.

It’s worth noting here that Link’s 2006 collection, Magic for Beginners, is a long-time favorite of mine; I remember reading the title story on its first appearance, and falling in love. So it is perhaps unsurprising that I enjoyed Get In Trouble almost from end to end — a rare feat for a short story collection. On the whole, Get In Trouble felt like it stayed a little closer to reality than Magic for Beginners, but I can’t quite pinpoint why I feel this way, because on reflection it really doesn’t. I suspect part of that impression may come from the combined offices of “I Can See Right Through You,” which centers on a man referred to as “the demon lover,” though how demonic he actually is remains in question, and “Secret Identity,” in which a teenaged girl from the midwest goes to New York to meet with the man she’s been catfishing in, basically, Second Life — a meeting slated to take place in a hotel that is host to two simultaneous conferences, one for dentists, and one for superheroes. “Two Houses” was another late-collection standout, reframes the gothic conceit of people sitting around and telling ghost stories in the context of people doing this on a spaceship. “The Summer People,” the first story in the collection, was also phenomenal — but, again, I could say that for almost every story in the collection. I just really like Kelly Link.

I love this cover design, too.

After Get In Trouble, the next book I finished was the third installment of the aforementioned Circle Opens tetralogy, Cold Fire, but having completed that, I hit upon another nonfiction piece that I burned through at speed: Esme Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias. I first became aware of this book by means of a display at Wise Blood KC (thanks, friends!), and on further investigation learned that it was the recipient of the Graywolf Nonfiction Prize for 2019, which is cool. A number of the essays in the collection were previously published, and on reading some of them, I definitely felt the sneaking suspicion that I had read them before.

But so what? Wang’s prose style is detached and compelling; her balance of data and personal experience impeccable. According to Wikipedia, the book was borne out of a particularly severe and unusual episode of psychosis, which became the essay “Perdition Days,” in which Wang details her experience of Cotard delusion. While this particular essay hews a little closer to conventional memoir, others, such as “High-Functioning,” catalog meticulously the experience of masking mental illness with fashion; others still, such as “Reality, On-Screen,” and “The Slender Man, the Nothing, and Me,” examine the ways in which mental illness, and specifically schizophrenia in its various forms, interacts with and within popular culture. The collection rounds out with “Chimayo” and “Beyond the Hedge,” both of which explore, in different ways, Wang’s experiences with spirituality and ways through both her various mental illnesses and her subsequent diagnosis with chronic Lyme disease.

But what struck me the most about the book as a whole is Wang’s insistence on her boundaries, her terms. While in its review, the LARB suggests this may be slightly disingenuous, I thought it marked a particular strength: in a field crowded with titillating displays of the absolute-worst-it’s-ever-been, Wang’s collection explicitly states how much she intends to reveal, and how much is none of the reader’s business. It was a refreshing change, as was Wang’s repeated insistence on her own agency within and with respect to her experiences; even in the book’s darkest moments (personally, I found the essay “Yale Will Not Save You” especially difficult to read), this adamant, burning agency compels both the reader and, it seems, Wang herself.

The covers are not good. In my recollection the hardcovers were nicer, but since I read all of them on my phone I didn’t really have to look at… this.

And now, of course, we come finally to my discussion of the Circle Opens tetralogy, which concluded with Shatterglass. The series is a follow-up to Pierce’s earlier Circle of Magic quartet; where that series detailed Tris, Daja, Briar and Sandry as young mages with craft-oriented powers learning how to use their magic and saving a bunch of people from pirates, plagues, and other bad shit, this one chronicles the four’s adventures after becoming fully-certified mages and travelling with their mentors (except for Sandry, who remains in her home country, acting as a sort of assistant to her uncle, who is a duke). The books, broadly, follow similar structures: character arrives in a new culture or milieu and simultaneously discovers that they must take on a student, despite being only 14 years old themselves, and prevent a crime, all while furthering their own magical development.

While the series as a whole is somewhat formulaic, it’s scarcely a bad formula, and honestly, if you’re an adult reading Tamora Pierce, you probably know better than to be reading for the plot. Pierce’s influence is pervasive in the world of YA fantasy, and for a lot of people (including, unsurprisingly, Leigh Bardugo, mentioned above, and yours truly) it was positively formative. And unlike certain other notable YA fantasy writers, she’s not a fucking transphobe — in fact, rather the opposite. But all that aside, I’m personally of the opinion that anyone who wants to write a really fucking compelling and coherent magic system should be reading Tamora Pierce, and especially the various Circles. It helps, too, that her characters are interesting and well-realized: the way the young mages in the Circle Opens navigate being accredited as adults but still, in fact, children is especially well-rendered. And if the series occsionally lacks nuance — which I feel is debatable — it is never to such an extent that the reader is pulled out of the story.

So that’s what I’ve been reading the last month and a half-ish. I actually finished another book today (entertainingly, it was Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, and since it’s the eleventh one I’ve finished there’s half a joke there that I can’t quite seem to make right now), but I’ll reserve that for the next round-up. Happy reading, friends.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)