Synthesized Ludology: Notes on Game Design

So I’ve been thinking about trying my hand at game design again lately. This is table-top role-playing game design: I don’t really know how to code and have very little capacity with art, so video games are out, and I’m a lot less interested with board and card games. This leaves tabletop RPGs. We’ve written a couple of times about our love for this genre, and there’s a pretty good reason why: it’s essentially a tool for generating narratives.

All of this being said, a lot of the critical writing on game design qua game design is kind of lacking. Some of the best stuff I’ve heard relating to it comes from the Podcasts Another Question, Bonus EXP, and Flail Forward (my three favorites, in roughly that order; the Gauntlet Podcast is also a very good resource, but that usually only incidentally gets in to game design.) I’ve also done a little bit of reading on the topic outside of my listening, discovering some of the things written about video game design that tabletop designers have brought over.

So, in the interest of making this all more digestible, for both myself and others, I figured I’d synthesize what I’ve read on Ludology and create a sort of master resource.

GNS, Trad, and Indie

This image was going to come up, so let’s just get that out of the way.

The first thing I ever read on Game Design laid out the GNS triad. As of this writing, I forget who first came up with this (I think it was Ron Edwards over on the Forge) but the basic idea is that games can be games first, narratives first, or simulations first, or they can be some combination of the three.

It all started here. We’ve (thankfully) gotten away from that. Uploaded by Matthew Kirschenbaum to Wikipedia under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Game-forward games tend to have clear-cut winners and losers, they tend to have clear-cut win-conditions and lose conditions. These are some of the most primitive TTRPGs out there, because they tend to throw back to the war-game roots of the genre (all RPGs are descended from Dungeons and Dragons [1974], which is a modification of war games, which emerged, ultimately, out of George Leopold von Reisswitz’s Kriegsspiel [1821].)

Narrative-forward games tend to have no clear-cut winners and losers, and be instead focused on creating narratives. Characters exist not as player-avatars but as components in an unfolding story, and playing the game successfully means helping to steer the narrative towards a satisfying conclusion. Early examples of this might include Ars Magica, though Dogs in the Vineyard is a much more recent starting point, and Apocalypse World is one of the most popular of recent ones.

Simulation-forward games tend to be focused on modeling, as accurately as possible, what happens when and how it plays out. Dungeons and Dragons, especially in the 2nd through 4th incarnations is heavily Simulationist, and for a while (especially from 1990 - 2010), there was a profusion of very detailed, very granular systems.)

You can, of course, have hybrid systems. A Gamist-Narrativist hybridization might give you a game like Fiasco; a Gamist-Simulationist hybridization can give you something like Battletech. A Narrativist-Simulationist hybrid could be something like Chronicles of Darkness.

This is, of course, only one possible lens through which to examine this subject.

One of the more common alternatives is the division between “trad” and “indie” games – which makes about as much sense as talking about “pop” and “indie” music; the terms have become divorced from their original, mode-of-distribution meaning.

Roll (d20+Con) to eat the carrot, and pray you don’t roll a 1. Comic taken from TvTropes, ultimately from from Abstruse Goose,

“Trad” games were originally games like Dungeons and Dragons, GURPS, Traveler, RIFTS, and World of Darkness. They were unified not by a subject or an aesthetic, but by a particular design philosophy (which, coincidentally, meshes fairly well with the “simulationist” category I’ve mentioned above.) Trad games have, it seems to me, two main defining features: they are all about providing options for people to pick from – players select a class and then have a predefined list of things that they can pick in there; or they pick options from a list a la cart, and that’s that (one of the surest signs that you’re looking at a trad game is that there’s a large and granular “skill list”.) They also model everything isomorphically. By this, I mean that everything it applied linearly across the board: each additional point in the “Strength” stat means you can carry X pounds more weight, you can jump Y feet further from a running start, and you do Z more units of damage. These systems are often used to model different things, meaning that you can pick up a wheelman from Spycraft, a half-orc sorcerer from Dungeons and Dragons, and a cyberpunk repoman from d20 Future and have them go (roughly) toe to toe.

The Indie design philosophy, though, tends towards much lighter-weight systems: how much can you carry? Who cares? Can you jump far enough to cross the chasm? Is the question interesting? How much damage do you do? The only two valid answers are “enough” or “not enough”?

In short, Indie design philosophy is much more geared towards smaller teams of producers – lightweight systems are easier to teach, require less referencing, and tend to be made by smaller teams. Part of the reason that Trad games have so many supplements is that they’re driven by the need to produce profits between two editions, and so they need granular systems that have a lot of stuff to plug in because otherwise they aren’t profitable. Indie games work on much narrower margins because they tend to be POD or ebook only, and have fewer people that actually need to be paid.

You can get to the end of an Apocalypse World game in 6-8 sessions. You’ll probably advance your character once in the same length of time in Old World of Darkness.

These material conditions influence the desired play experience and the mode of production. They’re not generally meant to be used to run 5-year-long campaigns. They can often be picked up and put down for one-shots or short series, and are designed to be satisfying in these chunks by cutting out the unnecessary portions. Indie games don’t tend to overflow with character options, but tend to emphasize development, and their systems tend to be loose, leaving things up to Gamemaster (GM) Fiat.

Recently, I’ve also heard about Trad-Indie hybrid or “Trendy” games as well as Post-Trad games. The example I’ve seen for “Trendy” games are the “Year Zero” system, which tend to feature extensive skill lists, but lack the strict isomorphism requirement, leaving more room for GM fiat. Post-Trad games, like the often-mentioned Invisible Sun, as well as other games by Monte Cook tend to have heavy isomorphism and fairly nebulous-but-extensive skill lists, but emphasize many of the more narrative-focused turns seen in Indie games. The big one that I’ve seen identified as such is the “character arc” mechanic from Invisible Sun, which pushes authorial control onto players and gives them the chance to define the direction of the narrative by choosing what leads to advancement, and thus where the incentives lead them, with the Gamemaster becoming more of a facilitator for this.

Fundamentally, the Trad vs. Indie split can be thought of as representing a “high” vs. “low” fidelity approach to representation. While in most media (David Lynch films excepted) it is considered to be generally better to have higher fidelity, this question is open in games: given the purely analogue nature of most games – a quality that I, at least, consider to be one of the biggest selling points – all of the math must be done by people and all of the tables have to be referenced unless committed to memory.

The longest-running game I ever GMed was a Dreadful Secrets of Candlewick Manor game using Monster and Other Childish Things, by Arc Dream Publishing.

This means that a “trad” game generally takes longer to play than an “indie” game, because of the greater granularity, which is a feature of the isomorphism. Now, this isn’t always the case: the One Roll Engine, which is used for games like Monsters and Other Childish Things managed to be fairly quick and fairly granular (managing to fit into a single roll both the speed and effectiveness of an action, as well as modeling in combat speed, damage, and location of a given hit – it’s a remarkably tight bit of game design.)

All of that being said, it generally holds true that Trad games have a higher barrier of entry and a slower speed of play than Indie games, though they also tend to enable longer-running play: it’s generally considered the case that Apocalypse World, and derived games, tend to max out around 6 sessions, with some people experimenting with specialized systems to allow play for as long as 10-15 (Jason Cordova was working on one called The Between that he occasionally discussed on the Gauntlet blogs, but the last mention of that that I spotted was from March of last year.)

MDA Paradigm

The MDA paradigm is something that came out of video game design – the acronym stands for “Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics” – Mechanics referring, here, to things like controls and movement; Dynamics is how these Mechanics are clumped together by the designers to provide a structure, things like level layouts and scripts; Aesthetics refers solely to player experience. So, for the designer, the game is considered in the order of M D A, and for the player it’s often thought of as A D M.

An interesting question. I’m not sure why one would want to, but you do you.

This is a bit more nebulous in tabletop design spaces, but we can link it to GNS fairly easily: Gamist approaches emphasize dynamics; Narratives approaches emphasize aesthetics; Simulationist approaches emphasize Mechanics. Of course, this isn’t going to be 100% true across the board, and is something of an oversimplification. But many people who start homebrewing after playing a lot of D&D try to think of how to make the mechanics do what they want (the Another Question episode on trying to adapt The Matrix into game systems touches on this when they look at a d20 attempt, which focuses on modifying strength to achieve the acrobatic moves from the movies – an approach which, by necessity, leads to a boatload of unintended consequences, because it’s attempting to set things mechanically which should be aesthetically-bound. It doesn’t matter if you can model the things from the movies if it doesn’t feel like the desired outcome.)

In tabletop design, Mechanics include things like how dice-rolling and task resolution are handled. Dynamics are how these things fit together to make a character and situation. Aesthetics is how it creates an experience at the table in question.

One thing that occurs here is that designers can only effect something from the same or a higher level: a Mechanical problem can’t be solved with a Dynamic intervention, only another Mechanical one. A Dynamic problem might be solvable with a Dynamic intervention, or possibly with a Mechanical one. I happen to think that same-level solutions tend to be best, myself.

Take, for example, safety tools. This is something that has come up in game design in the past few years, often centered around the first and most popular of the safety tools. It, essentially, functions like the “safe word” practice that emerged out of BDSM communities (I’m going to guess that there’s a non-zero overlap between “BDSM enthusiasts” and “tabletop gamers”, and I’m going to guess that it’s a bigger overlap when you change the second term to “tabletop game designers.” I’m not sure why, but this feels correct.) In short, when a player taps a special card with an “X” written on it, the scene has to stop and redirect, because the player no longer consents to the situation at hand unfolding.

Now, there is potential for bad-faith abuse (player taps it when he gets hit in combat, etc.) but this type of behavior tends to be policed at the table. This is an excellent aesthetic-level intervention for the aesthetic-level problem of a hostile play environment. I’m not completely sure that a mechanical-level or dynamic-level intervention could really handle the same issue.

Eight Kinds of Fun

One of the most seminal ideas in ludology that comes out of video games is the classification of “fun” into eight distinct categories. These categories are Sensation (game as sense-pleasure,) Fantasy (game as make-believe,) Narrative (game as story-in-progress,) Challenge (game as test to be overcome,) Fellowship (game as social opportunity,) Discovery (game as mystery to be unveiled,) Expression (game as blank canvas,) and Submission (that is, game as mindless pastime.)

As mentioned, this comes from video games, and it seems to me that a tabletop RPG is going to have most – if not all – of these. Rolling dice is sense-pleasure, portraying a character is make believe, but creating the character is expression. Moreover, you build a narrative together, discover things, overcome obstacles, and do a job within the framework of the party.

Of course, if you’re playing Chuubo, you’re probably looking for something different than the guy playing Vampire. Written and designed by Jenna Moran, available from DriveThruRPG.

I’d say that all of these are present, but I would also say that different games prioritize these differently. Diceless games – while often possessing some of the most innovative design out there – tend to deprioritize the “sense-pleasure” aspect. The feel of the dice and the clattering sound is a major component of this (and more important than it is often given credit for.) Many of the most successful of these tend to replace dice-rolling with token-exchanging as a sort of sense-pleasure. Games that heavily feature modules (pre-packaged “adventures”) tend to devalue or, at least, limit expression – though whether limiting expression devalues it or not is an open question.

Personally, I would say that tabletop games are worst at the “submission” portion, insofar as the definitions I found refer to it as “mindless pastime.” However, taking part in play and consenting to be the subordinate party in an arrangement for a time is something that a number of people do enjoy (see prior meditation on BDSM.) So if we take that other definition of Submission, things can become somewhat clearer.

If we fit the Eight Kinds of Fun into the MDA framework, this gives us a vocabulary for what kind of “A” the “M” and “D” are attempting to create. No tabletop game is going to aim for just one of these, just as almost no painting will ever be made that features only blue, yellow, or red: an experiment may be done, but it is done for the sake of the experiment.

An Aside: Dice Mechanics as Genre Concern

I don’t generally give a lot of credence to heavily simulationist games that use the old-fashioned 20-sided die to generate probability – or percentile systems for that matter. The choice of central dice mechanic (usually, with d20, this mechanic is “roll a die and add a pre-selected modifier, and see if you get over a target number”; with percentile systems, it tends to be “roll under a selected skill modifier on these percentile dice”) is a genre concern, for two particular reasons. First, it means that the best outcome and worst outcome is as likely as the average outcome, which is best for pulp-type games. It also enforces character specialization by strongly skewing the probability for certain tasks so that only people who have specialized in it can do it.

This latter has both an upside and a downside: first, it means that specialization is a viable strategy for making a character, but it also means that specialization is a necessary strategy for making a character.

D. Vincent and Meguy Baker’s Apocalypse World. It’s a seminal game, but I get the sense that the Bakers are slightly frustrated (perhaps “bemused”) with how others are modifying their work, hewing too close to the actual system instead of using the principles.

Compare this to a system like Apocalypse World, where players are rolling two six-sided dice and adding between 1 and 3, based on inherent statistics and situational concerns. They are always aiming to get past two particular gates: that between success and failure at 6 (7+ succeeds), and that between partial and complete success at 9 (10+ completely succeeds.) The issue here is that an average outcome is eight times more likely than both the best and worst outcome. It seems to me that this puts an interesting twist on the simulationist argument: it’s technically more realistic, simply much less granular.

As we can see here, the central mechanic of a system encodes a certain outlook about the place of the player characters within the game world; and this is only considering dice mechanics, it’s completely leaving aside the complex probabilities of systems that use cards to determine success and failure on certain tasks.

Fundamentally, the issue when looking at task resolution mechanics is “does this reflect the tone of the story I’m trying to tell?” Because a story about normal people trying to survive a monster attack and a story about demigods asserting their power should not feel the same. This sort of thing is part of why the Old World of Darkness games were never able to supplant Dungeons and Dragons as the premiere RPG: there was fundamentally a disconnection between what the mechanics said and what the game was trying to do (N.B.: more recent editions have largely corrected this.) But quite often designers throw in mechanics without thinking about how they effect the tone of the game, and tone is one of the most important concerns.

Connecting These To My Own Aesthetic Writing: Paradigm and Syntax

I don’t intend this piece to be a pure review of what other people have said; I have written a number of things on a variety of subjects, and there are a few ideas I wish to bring in. Chief among them are the concepts of the “Paradigm-Syntax” dyad (which can be connected to the GNS or the MDA sections) and that of “Complex Pleasures” (which connects to the Eight Kinds of Fun.) I also have the compulsory commentary on Nostalgia and Genre that readers of this blog will know is coming.

So first, the Paradigm-Syntax dyad.1 This is what I tend to use instead of talking about genre, because it’s an interesting way of clumping together different artistic experiences across what we normally call genres. Essentially, I think it’s important to look at stories – or other artistic experiences – that are fundamentally the same and figure out the “paradigmatic” version of that story: the most minimal form that can exist if you carve away all of the extraneous portions. If you can do this, then you can generally figure out places where you can change things and create something new.

A weird little game that I would like to actually try sometime.

So...the question occurs to me, how can we say that there’s any sort of connection between say, Something is Wrong Here or Fiasco, Chuubo’s Marvelous Wish-Granting Engine, and any given OSR game? If we could figure that out, then we might be able to define what an RPG is.

We can’t pin it down to dice – Chuubo doesn’t have that. We can’t pin it down to storytelling with a referee – Fiasco doesn’t have that. We can’t pin it down to equally shared authorial vision – OSR has a distinct imbalance. What do they all have?

I would say it is the use of language – and in many cases the social contract itself – as the medium of expression. Given that RPGs do not necessarily need to be played to win (as chess, checkers, go, poker, and similar games are) then I find that the barrier to saying it is an art form is somewhat lower. I would say that this is the Paradigm for the RPG: a group of people tell a story using a mechanical framework to determine what is allowed to happen.

Or, to put it plainly: it’s a machine built out of language to tell a story.

There are certain conventions, but those can be peeled back and the result would still be an RPG. They’re Syntagmatic. Consider: there exist One-Player RPGs (even Zero-Player, but that’s more of an art piece,) such as Plot Armor and Alone on Silver Wings. Everything that doesn’t work as a story-telling engine, a linguistic-mechanical framework, is superfluous.

It doesn’t really do The Breakfast Club that well. But you can hack it. Designed by Avery Alder, published through DriveThruRPG.

Now, some might say that this renders the game itself superfluous: if this is all it is, then why not just play make-believe like you did in the schoolyard? The answer is simple: to add novelty. These mechanical frameworks are mechanisms of Control that make some decisions easier and some decisions more difficult without necessarily preventing you from doing it. Do you want to run The Breakfast Club in Monsterhearts? You can: it’s just going to keep trying to make it Buffy: the Vampire Slayer or Twilight. Do you want to run Perdido Street Station in Dungeons and Dragons? That’s fine, but it’s going to keep trying to make it into Conan: The Barbarian or Elric of Melnibone.

This brings us to genre. One of the biggest Trad/Indie divisions that I’ve noticed that doesn’t really seem to get commented upon often is that Trad games often have an explicit setting, while Indie games have (at most) an implicit one – if not rules for creating your own setting as part of setup. In short, to use my Paradigm/Syntax dyad, Trad games are often syntagmatic reproductions of things: they’re trying to be something like Game of Thrones or Ghostbusters or similar. Indie games tend to be about paradigmatic reproductions of genres. You’re not going to be Jon Snow or fight Gozer the Gozerian, but the Indie game is trying to create systems that allow you to re-experience the emotional state you were in when you experienced the originals that they draw from.

This is generally why I tend to like Indie games more: they focus on the experience instead of the details, and that’s really what needs to be focused on. On this website, I have railed against empty nostalgia so many times, and this is fundamentally why I have a problem with it: nostalgia is often the statement “hey, remember this thing?” and saying nothing more about it. It’s syntagmatic reproduction of something. Much more productive is to not worry about the syntax, about the surface-level details, and focus on the core of the experience, and aim for a paradigmatic reproduction.

Because a Paradigmatic Reproduction is the first step toward real novelty – maybe, after you’ve recaptured a particular feeling, you can decide to move past it, and try to evoke a completely different feeling altogether.

Connecting These To My Own Aesthetic Writing: Complex Pleasures

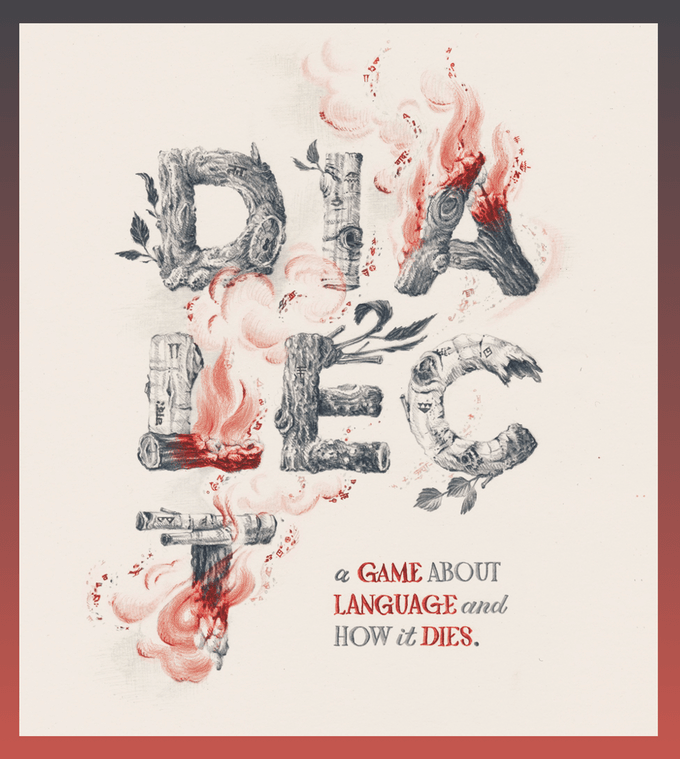

Not every game is fun. Dialect is a great game, but we don’t play it to feel good. Published by Thorny Games.

And this brings me to one of the core ideas in my aesthetic writing, and one that I honestly don’t break out often enough: the Complex Pleasure.2 Now, I happen to think that the Eight Kinds of Fun are not the only reasons that someone might seek to play a game; one of the games I mentioned up above, Something Is Wrong Here is quite the experience, but is not necessarily fun. I could say the same thing about the game Dialect. Both of these games, as well as our oft-returned to subject Invisible Sun, have a great deal of fun to them, but part of the desire to play them comes from the experience of “bleed.”

“Bleed” is often talked about in actor circles, and entered tabletop roleplaying through its weird younger brother, LARP. This is the phenomenon where the player begins to experience emotions that they portray their character experiencing: including not generally pleasant ones, like grief, rage, loathing, and sorrow. The desire to experience these things is perhaps less pronounced than “fun” but but is definitely present, and “fun” can be a secondary effect.

It is this very fact, the experience of bleed, that made me conceive of Complex Pleasures to begin with, and it seems to me that it is essential for future designers design for more than just fun. Not because fun isn’t important – it’s why we play these games, after all, – but because we can find enjoyment in spaces beyond the prosaic enjoyment the older games offer.

My original name for the Complex Pleasures theory was the “Tragedy Test” – if a medium can carry Tragedy, then I think it can unquestionably qualify as art. The key here isn’t that it isn’t enjoyable, but that the enjoyment is brought about by a moment of catharsis, an emotional release caused by the resolution of a fundamental tension – the terrible thing that you know is going to happen does, and because that’s over and done with, you feel a moment of release.

An aside: I’m stoked about Geist 2E.

This is something that I believe was being groped towards in earlier “edgy” games like KULT, Nephilim, and the World of Darkness. These games play with darker themes, and I feel that they were trying to provide grounds for something like catharsis, but I feel that being too beholden to in-the-moment fun resulted in them losing sight of this. More recent Onyx Path games, the ultimate descendants of the World of Darkness – especially Changeling: The Lost and Geist: The Sin-Eaters – I feel have reclaimed a bit of this: they provide the tools for playing through an unpleasant situation and emerging into a more emotionally fulfilled space beyond it.

In addition, the various World of Darkness games have always been on the forefront of opening the hobby and making it more inclusive — early on, this was the choice to use “she/her” as the default pronoun, normalizing femininity in game spaces. Today, just about every major role-playing game,*has a section on gender and sexuality, and it’s notable that the default “human” in the artwork for the newest edition of Dungeons and Dragons is a black woman. While there is certainly still space improvement, I feel that this is overall a positive move.

Where To Go From Here

I’ll admit, this is mostly me trying to chew over what I’ve read and arrange my thoughts in a way that allows me to start my own design work more effectively. So, while I’m going to finish with my traditional “what should we do now” sort of thing, this is mostly for my own edification. If anyone wants to try to do the same thing, I support them stealing the ideas, because that’s what designers do: steal, tweak, hack.

The current trend is towards more Narrativist games, and I think that’s a good way to move. Don’t worry too much about things like underwater combat rules or correctly modeling speed up and down a slope. Worry more about what the mechanics say about the genre of the game. Worry more about what emotional experiences the mechanics make more and less likely.

Speaking of that, don’t be beholden to make every moment more fun. A pleasure deferred is a pleasure increased, and if the experience of fun or fulfillment has to be put off for that, then so be it. Just not too put off: aim for a payoff every session, just make it worth it. And that payoff can be things other than fun: catharsis is a hell of a drug. People go and see Hamlet and Oedipus Rex when they’re put on, and neither are terribly fun.

This doesn’t mean that fun can be ignored, it means that if you don’t focus solely on fun, you still have a chance. You simply need to focus on finding a way to speak to the players.

1 - To explain, for those who don’t want to click on the link: the difference between Paradigm and Syntax is roughly the same as between recipe and meal, though that doesn’t quite cover the whole thing. Paradigm is more about what a work of art is trying to do. Is it trying to be a tragedy, a comedy, an epic, etc. Syntax is more about how it’s trying to do the thing, the moves that show up on the page of screen to make the Paradigm come true. If you’re interested in this, I’d recommend you click on the link.

2 - If you don’t want to click through: a Complex Pleasure is a feeling or experience that a reasonable person might not only consent to experience more than once, out of something other than biological necessity, but could seek to experience multiple times in a non-compulsive fashion.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)