A Thing Is as It Does: Notes Towards a Process Aesethetics

Well, the primary isn’t going the way I want it to, so it would make sense for me to write on that, make an impassioned appeal for people to support my preferred candidate (and you all can guess my preference, I’m going to wager.) I’m not going to do that, however. The blog on this website is principally about aesthetics, and I feel it’s time to turn my attention back towards that. For this week, at least. I make no promises about the next.

Also, just as a corollary and reiteration to Monday’s announcement we are publishing our first ebook on the 21st. It’s called The Horn, the Pencil, and the Ace of Diamonds, and it’s a contemporary fantasy book that deals with magic and an oddly philosophical zombie outbreak.

The proofs are complete, with layout by Edgar, and the artwork is fantastic, done by the wonderful and talented Cassie Allen.

But I should jump ahead to the topic I want to cover today.

※

Lately, I’ve been haunted by a phrase: Process Aesthetics. I want to sketch out a potential perspective that fits this phrase, though I am not at this point stating that it is my perspective.

Father Teilhard de Chardin wants you to stop arguing about creationism.

Process Philosophy is something that I was introduced to in either 2006 or 2007 (I forget which; depression compressing my psychological experience of time and anxiety dilating it makes the establishment of a strict chronology somewhat difficult at times) by the backdoor route of a college Theology class. I have sixteen years of Catholic Education under my belt, so it should come as no surprise that I’ve taken a number of theology classes, and since eight of those sixteen years were with the Jesuits, it should come as no surprise that there was a fair amount of rigor to those classes. It was something mentioned in passing near the end of the Spring semester, in relation to Latin American Liberation Theology, and it connected in my head with the theology of Jesuit evolutionary biologist and (to me) failed heresiarch Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

It sat in the back of my head for a long time, ironically doing nothing, just part of the furniture of my mind through graduate school and a long period of my post-college life. In the past few years, though, I’ve been bombarded by a string of fascinating references to it, in the form of our favorite non-Fisherian philosophers, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, as well as the presocratic Heraclitus, and references to the thinking of indigenous peoples all over the world – I’m planning on buying copies of Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion by James Maffie and Cannibal Metaphysics by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro.

“The road up and the road down are one and the same,” is some primo depressive realism. Painting of Heraclitus by Dutch artist Johannes Moreelse.

In short, while this philosophical tradition lies counter to most of the Platonic and Aristotelian thinking that has dominated so-called western philosophy, that does not mean that it is a recent innovation: philosophy that privileges Becoming over Being has been with us for a very long time.

While there are many wrinkles and strange differences between thinkers – Heraclitus is in one camp, Hegel in another, Nietszche in a third, McTaggart and Bergson off on their own, and Deleuze as a nomad that wanders between them all – there is a basic commonality that allows us to identify what these thinkers are and group them together. Privileging Becoming over Being means saying that the basic ontological unit is not the thing or the substance but the event. Over the whole span of time, the important things are not the static, perennial objects but the points of contact, the times when one thing changes into another or comes into contact with another.

It’s about what happens, not what is.

This raises a completely different set of concerns than our esteemed Athenians had, two and a half millennia ago. Questions about the nature of time and the nature of identity over time; questions about motion and stillness.

So that’s Process Philosophy, what would a Process Aesthetics be?

Our bodies are not a closed system, we interface with the environment readily — and if your body is, how can you expect your mind not to be? It interacts with your body, doesn’t it? Or are you a ghost being dragged around behind a zombie?

On Monday, when talking about the Covid-19 and the broader response to it, I set forth the postulate that “there is no such thing as a closed system”, and in the past I have set forth the postulate “a thing is what it does.” I feel that these can serve as the foundation for a Process Aesthetics.

The goal of art is to produce feeling. A work of art that concerns itself with making an intellectual argument may be good, but it is so in spite of itself. A work of art that persuades to adopt a philosophy or ideology or religion is propaganda, and if it is good, it is in spite of itself.

An artwork that engenders a powerful feeling – even one of disgust – is a successful artwork. I put forward a Theory of Complex Pleasures in the past, and have even gotten some mileage out of it, and I’m just going to drop that in here instead of focusing on arguing that the goal of art is to produce a feeling. It’s more detailed and I stand by it.

I have also discussed in the past the issues of Paradigm and Syntax. I’ve talked about them on their own, but introduced the concept in the context of architecture, but have also touched upon it in relation to genres and gaming. In this construction the Paradigm is the act, and the Syntax is the vector for it.

Allow me to elaborate: it is improper to talk about an “art piece” in my mind – art is always an active thing. I would prefer something like “art act” but to avoid coining too much extra vocabulary, I’m going to talk about an “artwork”, which I’ve already used and which is an accepted term and has an active sense to its etymology. The art work is, however, an act – it is an action, performed by an artist, that persists through time, the medium of its transmission into the future (including not just the physical substrate of the work, but also the aesthetics that communicate it, the individual events of any plot) as a vehicle for the artwork. They are the means by which it becomes accessible to other people, and the vector along which it travels through time.

The artwork is both this vector (the syntax) and a core that is the “recipe” of sorts, which I’m going to continue to refer to as a “paradigm” (if only because I’m pretentious and it sounds more dignified than recipe, and also because “recipe” seems to be more passive than I mean.)

The realism would not work without the abstraction, and the abstraction cannot work without the realism. The point lies in the interaction between them.

There is only one paradigm for a given work of art, whether as particular as a narrative beat or as abstracted as a unique quality. Consider the pivotal moments of prophecy and murder in Shakespeare’s MacBeth; the abstracted radiance and soft, realistic face of Klimt’s “The Woman in Gold”; the winding, uneven stones of Goldsworthy’s “The Walking Wall”; the moving blocks of tense sound in Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima.

When you experience one of these works of art, you are brushing against something that originated in the mind of the artist (or, in my preference, in the zeitgeist around the artist, and which they gathered together) and which was fired, blindly into the future: the script, the canvas, the stone, the sound, these are vehicles for this process.

I think it would be a mistake to think that we are experiencing all of these art work as the original creator intended, and I think it would be a mistake to think that we are experiencing these works of art as people at the time did: the students of rebels become the establishment, just as the children of barbarians become the new tax collectors and priests. What shocked and dismayed and led to riots is now the canon.

These older artworks interact with modern culture, and we can grasp the presence of intention, and while a Grecian urn may have decayed from a particular message to a general symbol of a bygone age, it strikes one differently than the capital of a column or a line of Homer: there is a trace of the original message, no matter how unknown or distant. There is a scrap of the original paradigm in the modern vector.

And each one you experience, each time you experience, changes you, and leads you to interact with the world differently. These tiny little systems, whether broken down cultural-linguistic mechanics of a Grecian Urn or the baffling howling of an avant-garde musical piece, plug into the “system” of your thinking, and a trace of them is left in you. Just as bacteria swap information through plasmids, so to do people and cultures transmit meaning through art. Each one alters your trajectory a little bit, and if you’re an artist, it pushes you in a new direction.

Which brings me to something else: I feel what I have said thus far is fairly intuitive from what we’ve talked about in the past, but I think it is incomplete. To Vector (or Syntax) and Paradigm, I once added myth. Let’s set myth aside for now. Let us consider, instead the Field of culture. Vector, Paradigm, and Field.

As these art works travel forward in time, they influence people around them – no one is a closed system, and these works of art influence those who experience them (and, through criticism, they influence the work of art as it travels through history.) But the interaction between them all forms the broader culture, what I’m referring to here as the Field – and which I used the slightly more accessible term “zeitgeist” for only slightly before. If each work of art is a missile fired upon a vector, the “culture” is actually the field, the dynamic space that is described by each vector – a vast tumbling mass passing through the possible space of all potential cultural arrangements, an eldritch tangle of angles and curves and tendrils that encloses what it conceivable and possible.

It’s a bit more exciting to me than just thinking of culture as something pinned up like a butterfly in a sterile environment.

Even if it’s just sitting there, it’s doing something. It’s having an impact. Still, it moves.

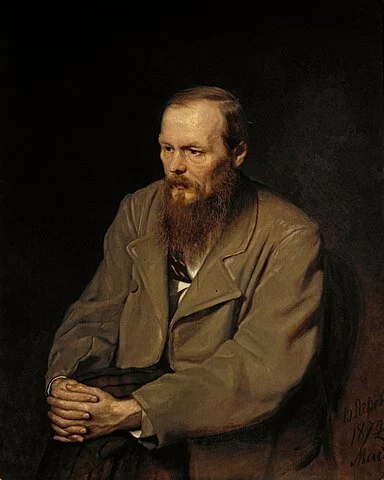

Fyodor Dostoevsky, as painted by Vasili Perov. Even the act of writing his name in Latin characters is an act of translation, because it’s a mistake to think that letters in different alphabets refer to the same sounds.

After stepping away to have a cigarette and do a bit of cleaning, I have given some thought to how to make use of this aesthetic theory. A theory without any applicability isn’t one that I’m terribly interested in – decry me as a mere pragmatist if you must – but, while I’m not necessarily going all-in on Process Aesthetics, I think having some applicability would be a good idea. Beyond just providing a bridge between my thoughts on Syntax and Paradigm and my thoughts on Complex Pleasures, which would be useful for me on its own, what does this do?

Let’s see.

Perhaps it could help explain translation and adaptation as providing a sort of meta-vector for a work of art: instead of saying that “Dostoevsky is a Russian translation of Dickens” or “this video of a man reading Beowulf out loud is our movie of Beowulf”, it is instead crafting an art-side adapter to allow people to experience something preexisting in a new medium (I hesitate to discuss translation at length; I leave that for Edgar, who has done far more than I, and more recently, and has more thoughts.)

It may also allow for a way to discuss meaningful equivalencies between otherwise unconnected artwork. We already talk about movies and books as being in genres, but these are vast moving blocks of otherwise unconnected works of art, and it seems to me completely meaningless to separate out the narrative arts from the non-narrative arts on this front, if we privilege instead the artwork-as-vector-of-emotional-response framing. Perhaps there are meaningful comparisons to be drawn between music, sculpture, film, poetry, and the culinary arts.

Another important thing would be allowing for a meaningful counterpoint to the so-called “hatred of literature” approach, which is endemic in the upper levels of the academy in comparative literature and English departments, viewing literature – and presumably in other faculties for other media – as something that is most meaningful as a mode of expressing the conditions and ideas of a particular time, instead of as something that acts in a pseudo-ahistorical fashion upon those who experience it.

Using an image of Jonathan Lethem, because he’s the one out of this lot the I like the most. Motherless Brooklyn and Gun with Occasional Music were good.

Framing artwork as a fundamentally active thing also helps peel away some of the invisibility of the dominant ideology of the time: focusing on literature, because that’s what I know the most about, but canonizing people like Davids Foster Wallace and Eggers, and Jonathans Franzen and Lethem as literary luminaries means that the ideas and things that they say about the world are simultaneously promulgated and rendered invisible, approaching the status of something like common sense.

So, while I’m not completely sold on this idea, I’m not going to toss it aside, just yet. I feel that this came together sort of by accident for me, but perhaps it is providential. Maybe I should test it out.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)