Breaking The Sheepdog Delusion: On Forming a Society of Solidarity

“This is the ideal male body. You may not like it, but this is what peak performance looks like.” —Police trainers, apparently.

Uploaded to Wikipedia by user AKS.9955, used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Near the beginning of last month, as the protests were beginning, I encountered references to Dave Grossman, a self-styled “killologist” who teaches police officers to respond to uncertainty with lethal violence. If you’re interested in this man, I recommend listening to the episode of “Behind the Bastards” on him – Robert Evans does a great job of breaking it all down, and provides footnotes so you can verify his work. What I want to talk about is something that forms a cornerstone of his training and which you find repeated quite often. It’s often called the “sheepdog mentality” but I prefer to swap out “mentality” for “delusion”.

The basic idea is that there are three types of people: the vast majority of people are sheep, (fundamentally harmless and fairly useless) who are preyed upon by wolves (bad people) and must be protected by sheepdogs (“good guys” who are willing to use violence.)

The problem is that this is nothing but a self-serving justification and fundamentally ignores a lot of very important factors. My first objection is to the idea that there are people who are inherently criminal. By claiming that criminals are actually “wolves” who are constitutionally incapable of not preying on “sheep”, you have already created an ethical justification for lethal violence.

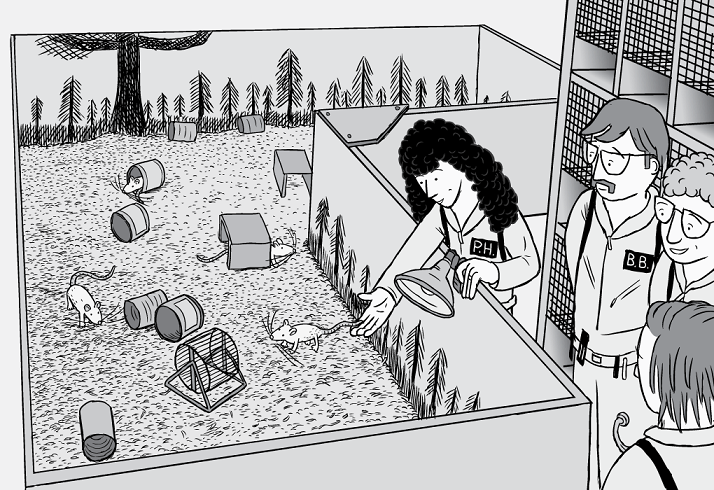

Image from Stuart McMillen’s Rat Park comic. That’s the ultimate source, but I took the image from the website Advances in the History of Psychology.

To explain my opposition to this idea, let me return to one of my old tropes: Rat Park. This was a study done at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia in the 1970s. In this study, some rats were placed, isolated, in cages and given the choice between opiate-laced and normal water; if I’m understanding what I’ve read, a large number of these rats died due to drug dependence. Other rats were placed in a “park” – a communal enclosure that had the same choice of drugged and normal water, but also had other features that provided stimulation. The rates of addiction or death appeared to be much lower.

My read of this is that drug abuse is principally – though not solely – founded on a lack of other options: you can sit in the cage sober or you can sit in the cage on drugs. You can live in a blighted neighborhood sober or you can live in a blighted neighborhood on drugs.

But if you adopt this reasoning, then it’s clear that other forms of so-called criminality are actually attempts to escape the cage. They are often misguided attempts to acquire resources that are otherwise inaccessible or to assert control that is not otherwise felt.

Which is convenient for people who benefit from the status quo to ignore: the economic system that we live under functions by siphoning wealth from every accessible place and concentrating it in the hands of those who already have it. Making use of the fiction that there are people who are inherently and essentially criminal to justify repression makes it easier to justify not redistributing a share of that wealth to everyone.

Of course, it serves more than financial interest. It would have to: completely eliminating the police and military (or, as I’m coming to think of it, the U.S.’s “cops without borders” program) from the budget would free up roughly $200 a month for every American taxpayer. If you offered every “criminal” a yearly payment of $2,400 to just not engage in criminal behaviors, I’m pretty sure that many would take it.

Metaphorical image of the people objecting to giving the impoverished anything.

The counterargument to this is that it’s naive and that these people would take the payment and just engage in criminal behavior anyway. Some, no doubt, would, but a large number of them would probably use that money to get back on their feet and do something else wither their time. This counterargument is pure ideology based on nothing.

There’s also the fact that, based on studies performed with children, it seems pretty clear that authoritarian power structures simply produce people who are more effective at circumventing those power structures. Strict parents produce good liars. Repressive societies produce people who are good at sidestepping the rules, which might suggest that the “wolves” are made by the presence of “sheepdogs”.

But the big problem occurred to me only after this one, and it shows up in the first syllable of “sheepdog delusion” – it presupposes the existence of “sheep”. The average human being, this mindset says, is stupid and easily led. In short, a person who inherently needs to be protected and guided.

Apparently not the ideal.

I don’t know about you all, but I’ve never felt that being compared to a sheep is complimentary. I just checked with Edgar1, we’re in agreement: “sheep” is never a compliment.

What we have here, I would say, is a parallel social class system. At the top are those who use violence right. At the bottom are those who use violence wrong. The vast middle stretch are those who don’t use violence. The nature of this mindset states that these are unchanging, essential parts of a person.

When your job is to protect stupid animals from a cunning predator, there are a lot of things that suddenly become justified. More so if the predator can blend in with the prey, as is not the case with real sheep and wolves but is necessarily the case in the sheepdog mindset. After all, any complaint being leveled at you is the bleating of a dumb animal.

The sheepdog delusion is a window into a deeper problem I’ve begun to recognize: the fundamentally Hobbesian mindset that a lot of our institutions are founded upon: they exist to terrorize the populace into compliance. Or, in the case of many Post-Reagan social services, frustrate them into giving up – if you don’t believe me, get on the phone with any government agency: this piece will still be here in four hours after your call is completed.

“Can we get this, but with Ronald Reagan’s head and an assault rifle?” — America.

Hobbes’s argument is, essentially, that in the absence of laws there is a state of nature, and in that state of nature life is “nasty, brutish, and short.” The state emerges to maintain a monopoly on the use of violence within certain geographic boundaries: it transforms people into citizens, and then maintains their compliance through the use of force and by inspiring abject terror in the citizens of the use of that force.

To clarify: all of these services have been cut deeply, privatized, or otherwise gutted. It means that interacting directly with them is made difficult because they don’t have the resources to respond to inquiries. Private bureaucracies have similar problems, but that’s because of the aforementioned wealth-siphoning.

If you believe that the vast majority of people are stupid and debased, then perhaps it makes sense to terrify them into compliance. Perhaps it makes sense to punish them for trying to access help: after all, if you offer them help, they will become dependent on it and become a drain. Perhaps it makes sense to create in them a sense of unease at interacting in any way with an agent of the state, because the agent of the state is trained to use violence or the threat of violence to ensure compliance with the demands being made.

It would be nice to move past 17th century solutions. If we do that, maybe we can move right past the 18th century solutions. Just a thought.

The only problem is that this argument comes at a modern problem with a 17th century solution. Of course, calling it a solution is absurdly generous: it is more of a perpetuation of the problem, because laws create criminality. It’s a form of social construction. For more information, see this Twitter thread from lawyer and writer Dave McKenna.

This intersects a bit with an idea I discussed last year, the Deleuzian-Foucauldian concept of “The Society of Control” – you’re free to do anything you want, but the barriers to things that the powers that be don’t wish you to do are higher and the costs higher. The police, on the other hand, are a trace left behind of the Society of Discipline, where compliance is maintained through violence and the threat thereof.

I’m going to just throw out there that this is not a terribly desirable situation. I’m going to guess that a lot of you are going to come with me on this.

What would a desirable outcome be? I’m not going to say “communism” or “anarchism” – those terms have too much baggage associated with them, and are more particular than what I’m driving at. Our solution for this must not be the creation of a new society of control, discipline, or sovereignty.

What needs to be built is a Society of Solidarity: a social model that uses solidarity between the members of the society as its primary mode of operation. By preventing the conditions that lead to dysfunction in the form of criminality and similar problems, it will become easier to achieve a desirable state: a society in which people are free to pursue what is meaningful to them.

Who has an article that came out today in Eidolon under their chosen name. Read it here. You can also still totally buy their book here.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)