We've Run Out of Ideas: First as Tragedy, Then as Farce, and Finally as Metaverse

Anyone want to strap on this bad boy and sit through a meeting that not only should have been an email, but is also an email? (Virtual Boy image taken from wikipedia user Evan-Amos and used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.)

(Because of how we get most of our traffic, I’m going to be talking around a few things. I’m going to trust that you can figure out what I’m saying, though.)

So, we’ve avoided talking about the idea of the Metaverse thus far.

Edgar sneers at the idea, saying that the very thought of it is stupid and also bad, which is true, but while they think that makes it beneath consideration, I regret to inform you that I think that this makes it ripe for commentary.

Let us start from first principles.

What a perfectly coherent book!

The term “metaverse” comes from the 1992 science fiction novel Snow Crash, by Neal Stephenson (a cyberpunk classic.) Fairly early on – the second mention of the term, the first one just being one of those cryptic background references that speculative fiction thrives on – Stephenson describes the central character using a computer to go from his squat in a self-storage facility into this other world:

So Hiro's not actually here at all. He's in a computer-generated universe that his computer is drawing onto his goggles and pumping into his earphones. In the lingo, this imaginary place is known as the Metaverse. Hiro spends a lot of time in the Metaverse. It beats the shit out of the U-Stor-It.

Hiro is approaching the Street. It is the Broadway, the Champs Elysees of the Metaverse. It is the brilliantly lit boulevard that can be seen, miniaturized and backward, reflected in the lenses of his goggles. It does not really exist. But right now, millions of people are walking up and down it.

The dimensions of the Street are fixed by a protocol, hammered out by the computer-graphics ninja overlords of the Association for Computing Machinery's Global Multimedia Protocol Group. The Street seems to be a grand boulevard going all the way around the equator of a black sphere with a radius of a bit more than ten thousand kilometers. That makes it 65,536 kilometers around, which is considerably bigger than Earth.

This is where the word comes from (also, the relatively common term “avatar”. It really feels like Stephensonian terminology eclipsed Gibsonian sometime in the late 90s: people still have avatars, but the term “cyberspace” is indelibly cringeworthy at this point). It’s a combination of “meta” (above or after) and verse (here shortened from “universe” but technically coming from “turning”). In short: the universe we construct above the universe.

The whole thing, in the novel, is sort of like Second Life, but using something halfway between holodeck (magic) and VR (real but terrible) technology to achieve it. This is all whatever – I do find one thing reasonably interesting here: even in the dystopic parody-cyberpunk world that Stephenson draws, the internet is run by a non-profit – the “Association for Computing Machinery’s Global Multimedia Protocol Group”.

Somewhat less coherent. Cyberpunk that failed to predict the “all my apes are gone” idiocy that we are forced to live through, now.

Closer to what is being proposed is the OASIS from Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One – most likely the only Ernest Cline book I’ll ever read, and probably just the once – where the world is dying and everyone uses this shared virtual space to handle everything. It’s supposedly owned by a private company but there’s a sort of ARG within the VR where one can acquire a controlling interest in the corporation that runs the OASIS, which is what leads to the whole dead-eyed, nostalgia-drenched and pop-culture-saturated everyone-claps-fest version of the grail quest that the story is about.

Now, around here, you may ask: why am I going over fictional antecedents instead of the actual proposed Metaverse?

Because it doesn’t exist yet – it most likely never will, as anything like what is being proposed – and it has the same problem that we can see in Snow Crash and Ready Player One, but it’s a weird new kind of dialectical shit sandwich. Snow Crash put forward this parody of cyberpunk, and Stephenson’s story effectively said “this is probably what everyone will concern themselves with as the world becomes ever more awful.” Kline looked at that, and said “what if that was privatized and full of 1980s nostalgia? Wouldn’t that be way more rad than the real world?” The world’s largest social media company looked at it and said, “Pay attention to us trying to make this instead of all the genocides we technically enabled.”

And, frankly, the offline worlds of Snow Crash and Ready Player One are more interesting than the online world. Some storytellers have even explored this sort of story from this angle, Simon Stålenhag, who is responsible for Tales from the Loop and Things from the Flood, did a book called Electric State that is just such a narrative.

Of course, I’m joking up above when I claim that this is being done to distract from the genocides. They predicted, correctly, that we would put all of that from our minds, and that we would forget Cambridge Analytica, and that we would forget the Facebook papers. Of course, looking back over this, my reaction to the whole situation is, essentially: “We shouldn’t make a metaverse, and if we do, you shouldn’t be the ones to make it.”

And, of course, my stance is largely contained in the first five words: I don’t think that the concept of the “metaverse” has legs. It simply feels like the same thing as Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), but you’re required to pay attention to it if we make it.

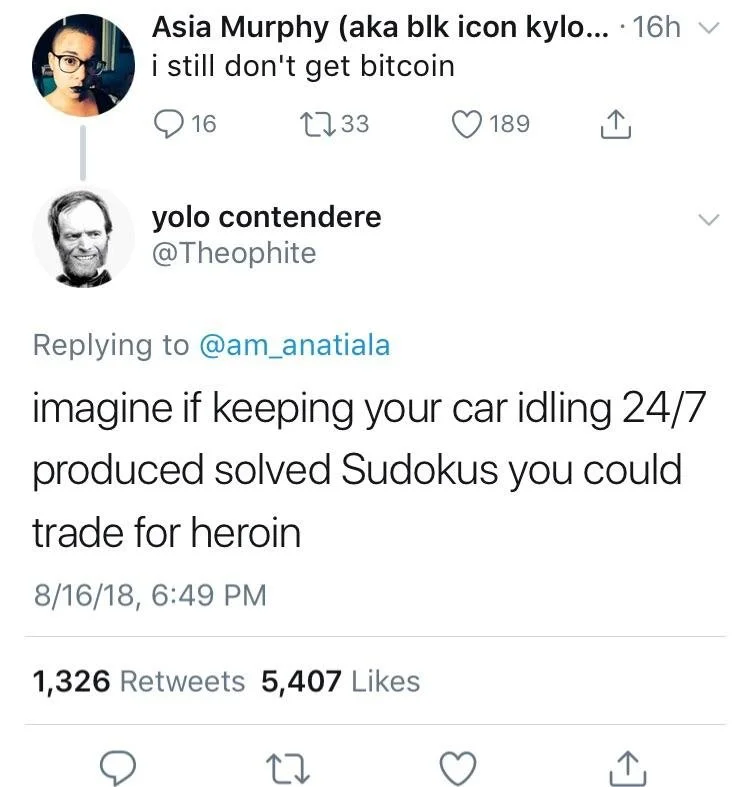

I have this image saved as “blockchain explanation.jpg” — it’s about bitcoin, but it’s basically this.

As an aside, to those who have heard explanations of NFTs and don’t believe that they understand them, I would like to suggest that you do understand the idea, but have perhaps missed that it’s basically just incredibly stupid money laundering. To those who haven’t even done that much, the basic idea (I feel) was best expressed by Dan Brooks on Gawker, in the article “The Future isn’t only Useless, it’s Expensive,” when he wrote that the art being traded, “combines the nuanced social awareness of computer programmers with the soulful whimsy of hedge fund managers. It is art for people whose imaginations have been absolutely captured by a new kind of money you can do on the computer.”

In short, it’s a way of establishing ownership of a digital object, thus introducing scarcity into the digital space – not of the file itself, but of the right to claim ownership over it. It’s sort of like owning an object that anyone can copy and make use of endlessly, but no one but you can meaningfully claim ownership over it, despite the fact that you have neither the right to sole use (usus) or the right to destroy it (abusus) – I don’t understand how it might interact with the third and final portion of property rights (fructus, the right to enjoy the profits or benefits of something).

I need to consider the implications there, actually: what is ownership if you cannot meaningfully assert that ownership?

In any case, the idea here is that NFT technology is a way of imposing scarcity on the digital, something that really only seems to have utility for Digital Rights Management: you buy something with real, actual money, and you’re issued a unique token that indicates that you have bought access to the thing, and then you use it to enable the streaming of a digital media file (ergo, a way to make you buy something without actually giving you ownership of the file).

The metaverse is the drunken collision of the NFT and Virtual Reality. It’s predicting a massive shared virtual world, where property rights are written directly into the code of the universe. This, I feel, is both stupid and bad. However, that doesn’t mean that something wouldn’t work. Only that it would be difficult and shouldn’t be allowed to work.

The metaverse requires NFT technology, because the verification of ownership is required – one of the big pitches is that in online gaming you’ll be able to take items from one game to another (like in Ready Player One), and to verify ownership, something like an NFT will be necessary (leaving aside the difficulty of making the same item functional across dozens of different engines).

No, the problem here is what we might call Rule Zero of scarcity from an economic standpoint: for something to be meaningfully scarce, it has to be something that people experience desire for.

Consider: in the course of normal life, we never consider botulism as being scarce. Nor is Radon ever considered scarce. Nor the common varieties of ants.

Advertisers will try to convince you to buy anything.

Only something that people want can be scarce. As a result of this we have the advertising industry, designed to manufacture new desires in the minds of the people that view the ads. They do this because the system we live in doesn’t really work unless they do. When there is a lack of free commodities – that is, when there are no new horizons of extraction to exploit – one has to be manufactured and it all becomes Tulipmania again. This is necessary, because capitalism doesn’t work without a free lunch: if there isn’t something that can be had for free, then the system eventually stabilizes into a zero-growth steady state. This is because – despite what the economists would tell you – the market is a zero-sum game.

When growth doesn’t materialize, the actors in the market panic, and when they panic they do dumb things. Currently, Meta exists because Apple changed how targeted ads work and so the incentive is for them to try to take ownership of the hardware. They’re trying to make a Hail Mary play to create a new kind of internet that they own all of the hardware infrastructure for.

CNET’s supercut of the one hour-seventeen minute reveal video.

Gilles Deleuze once said, “When you find yourself in the dream of the other, you’re fucked,” and this is exactly what’s happened to Meta: they find themselves trapped in a dream, specifically that concocted for the 2002 Stephen Spielberg-directed Tom Cruise vehicle Minority Report. Gestural interfaces are terrible – why would you want to perform a full-body workout for something that can be done with the click of a mouse? Why would you strap on a headset and give full access to a bizarre new system to achieve what can be done from your phone?

Do you remember 3D television?

This is going to be like 3D television.

Only it’s going to be one of the world’s largest companies pinning everything on the success of a technology basically identical to 3D television.

Or google glass. Remember how positively people responded to those?

So, to summarize: I don’t believe anyone wants a “metaverse” to exist, as it’s the collision of two dodgy technologies – blockchain-based NFTs and Virtual Reality – and while that might make sense for a game company to try to develop, it’s a big question for why you would want that to be your primary means of socialization, commerce and work. Beyond whether it should or should not exist, there’s even bigger questions of why the world’s largest social media company should be in charge of that, given all of the genocide.

A project like this is essentially a means to encode the values of a particular architect into the fabric of humanity’s shared experience. It isn’t necessary, and it isn’t good that this is something that someone is trying to do, beyond that it’s even worse that these are the people trying to do that.

It’s likely going to crash and burn – and the disruption from that is the good outcome.

Okay, so this is old news, but what is going on here? Why are you using VR if your car is there? Did you go to Walmart and put on a VR headset? Why not just shop like a normal person? Who thought this was a good idea?

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)