The Gap Between Memory and Identity: Scattered Notes

I didn’t work The Matrix into this piece, because it was already too damned long. In reading it, I’m sure you’ll be able to see where it could have fit, though.

Apologies beforehand: this one is going to be a rambling, stitched-together mess of ideas that I’m trying to make into a coherent whole.

I feel it necessary to, in the light of recent things I’ve written, to examine some older questions I’ve dealt with. This is, I will admit, partially triggered by listening to the excellent Weird Studies episode on the film Blade Runner, and, as with most episodes of that podcast, a great many unrelated topics were brought up and looped back in and woven through it: fiction-as-real-time-historiography; a comparison between Blade Runner, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman in terms of the medieval concept of the Great Chain of Being; and other, unrelated concepts.

However, it was the examination of the relationship between memory and identity that seemed most productive to me. To briefly summarize what was said on the issue, one of the hosts – musicologist Phil Ford – expressed frustration with the issue that most people who view the film consider to be most important: the question of whether or not Harrison Ford’s Rick Deckard is a replicant or not. Ford insists no, but the director, Ridley Scott, insists yes.

The other host, director J.F. Martell, brings in two Phillip K. Dick essays, “The Man and the Android” and “Man, Android, and Machine,” to sidestep the question: in the Phildickian conception of the world, “human” is an approach to existence, not a type of being. This means that an entity that behaves in a human fashion is a human, while an entity that does not behave in a human fashion is not, regardless of its history. In short: the question isn’t whether Deckard is a Replicant or not, the question is if any actual humans are presented in the film.

Kojève seen here doing a D.B. Cooper Impression.

When I heard this, I was put in mind of a passage from Hiroki Azuma’s Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals – previously referenced by me in the piece “We Have Always been Postmodern”, posted at the end of March – in which he references the interpretation of Hegel that was introduced to Japan by Russian-born French philosopher Alexandre Kojève, in his book Introduction to the Reading of Hegel.

Azuma summarizes this by saying that (and forgive the exceptionally long quote)

[i]n Hegelian philosophy, which was first developed in the early nineteenth century, the “Human” is defined as an existence with a self-consciousness, who through a struggle with the “Other” (also endowed with self-consciousness), will move toward absolute knowledge, freedom, and civil society. Hegel called this process of struggle “History.”

Hegel claimed that history in this sense ended for Europe in the beginning of the nineteenth century. … Of course, the mode of thought that sees the arrival of Western-style modern society as the conclusion of history has since been thoroughly criticized as being ethnocentric.

…Kojève emphasizes that after the end of Hegelian history only two modes of existence remained for human beings. One was the pursuit of the American way of life, or what he called the “return to animality,” and the other was Japanese snobbery.

Kojève called the form of consumer that arose in postwar America animal. His reason for using such a strong expression is related to the provisions for humans peculiar to Hegelian philosophy. According to Hegel (or more properly according to Kojève’s interpretation of Hegel), Homo sapiens are not in and of themselves human. In order for human beings to be human, they must behave in a way that negates their own environment, they must behave in a way that negates their own environment. To put it another way, they must struggle against nature.

Animals, in contrast, usually live in harmony with nature. Accordingly, postwar American consumer society – surrounded by products satisfying consumer “needs” alone and whose fashion changes accordion [sic] to the media’s demands alone – is not, in his terminology, humanistic but rather “animalistic.” Just as there is neither hunger nor strife, there is no philosophy. (p. 66-67)

Read through this lens – and I see no reason not to, because the explanation of Blade Runner’s Voight-Kampff test is largely a hand wave about physical responses that sounds an awful lot like a polygraph – the movie becomes rather different. The problem doesn’t become androids hiding among humans, the problem becomes (synthetic) humans living among animals.

In short, perhaps Blade Runner is, actually, They Live told from the other side.

I’m going to have to sit down and watch They Live and Blade Runner back-to-back before I continue on that line of inquiry.

Azuma’s line about snobbery – attributed by Kojève to the Japanese – is of minimal importance to my inquiry here, but perhaps I should summarize it before continuing: as an animal cannot help but live in concert with its environment, a snob refuses to live in concert with its environment. Where no possible conflict exists between the person and their environment can be conceived, the snob will contrive to manufacture one. This isn’t productive striving against nature or one’s environment, this is a bellicose refusal to accept the environment.

Of course, a bit of clarification about what is meant by “environment” in my phrasing and “nature” in Azuma’s passage might also be necessary. This is not about what is, perhaps misleadingly, called “the natural world” or “wilderness”: it is, instead, the environs that seem customary or fitting to the person. So in this read, for the suburban American, what is considered “nature” through the Hegelian-Kojèvian lens is treeless strip malls and ghostless housing developments.

The title of the book comes from the identification of Otaku – which is somewhat erroneously translated as “nerd” or “geek” in the American milieu – as an “animal” adapted to the “natural environment” of postmodern media production.

Of course, while things are somewhat different in Japan, one cannot consider the postmodern period of cultural production in the United States (and to a lesser extent in Europe) without considering Philip K. Dick – more so than Lyotard or Foucault or Baudrillard, he was Patient Zero of the postmodern condition, possibly due to his mutant epistemology making him strangely adapted to the new world he found himself in: Phillip K. Dick as some sort of psychic lungfish.

So let’s shake the metaphorical etch-a-sketch and look at one of the central questions of Blade Runner that the “is Deckard a Replicant?” issue really serves as a stalking horse for: What is the relationship between memory and identity?

In the novel, she was much more a femme fatale, but in the film Sean Young plays the character as much more of an ingenue — she spends the whole movie tormented by Deckard, and then it’s played a love story. Apparently, Young and Ford hated one another on set, and this comes across.

As the sequel (admittedly not present to the Scott text of the film or the book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, at least so far as I remember from the last time I read it) makes clear, the Replicants all have off-the-shelf memories inserted into them and these form the emotional baseline of their identity. Some custom Replicants, like Rachel Tyrell (played by Sean Young,) have bespoke memories, potentially based on those of a living human, but that does not make them any more independent beings: their memories are artifacts that they (metaphorically) carry with them, and the longer they live, the more likely they are to go mad from the disconnection between their experiences and their memories. For this reason, their lives are limited to four years (which, I’m sure, also means that the Tyrell corporation can sell a new one to each owner two-and-a-half times a decade. Shades of the iPhone).

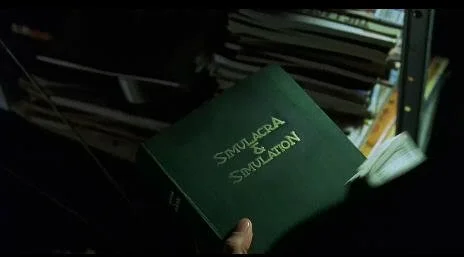

What is proposed here is, essentially, that the Replicants, despite being simulacra produced from a storehouse of potential memories remixed and spun out and unleashed on the world, have a certain individuality that is not explained by their memories – and it is the disconnection between the memories and this individuality that leads to problems.

This is a really important question: are people their memories, or is there some deeper element that helps to define who we are? In many places, I’ve suggested that we are conditioned one way or another by our environment to behave in one way or another – from this starting point, it would be very easy to say that we are nothing but the stories that we tell ourselves about who we are. Which means that, if we can be convinced to change the story, to start telling it differently, then it becomes entirely possible to change who we are.

Image: B.F. Skinner, noted Jackass.

There is a certain value to this. We know that people are shaped by their environments in one way or another, but shaping doesn’t always take. We can’t really go from this fact to the premise of something like B.F. Skinner’s unintentionally dystopian Walden Two, because we know two things for a fact: first, human beings are too complex to be conditioned and shaped like that, and, second, B.F. Skinner was a total bastard.

You have to look at the influence of the environment on a person as a probabilistic thing. Maybe the child of an alcoholic will grow up to be an alcoholic or a teetotaler, but you can’t just sum up all of the events that the child experiences and run some kind of psychodynamic calculus to determine how their life will end up. You might, however, be able to look at a whole population and say that X% of children with an alcoholic parent become alcoholics themselves, and Y% abstain.

Of course, this, in and of itself, is untrue: demographics themselves shift over time and it is not entirely possible to tell where they will go.

And at the level of the individual, this is perhaps less than useful.

Let us consider, instead, another pair of concepts that the aforementioned Weird Studies episode put me on to and bring that into play: Haecceity and Quiddity.

The hosts compared Blade Runner and The Thing in terms of these concepts: the Thing, from the John Carpenter Movie, had Haecceity (this-ness) but no Quiddity (what-ness), while the Replicants from Blade Runner were the opposite.

Quiddity, when you get down to it is the subject of demographics: it is the classification of people and things, their ability to be separated out and placed into an ordered set of categories and counted. It is a question of qualities reduced to quantities.

Haecceity, on the other hand, is the absolute individuality of the thing: it’s inability to be categorized and classified into a box. If Quiddity is the subject of demography, then Haecceity is the ostensible subject of psychology.

One of the instances of the titular thing — imposing arachnid, mollusk, and arthropod traits onto a human head.

The Replicants are simulacra: they are “individuals” constructed from a database of pre-existing individuals. They have nothing but quiddity. The Thing, on the other hand, is an infectious overlay of so many “originals”, cut, remixed, chopped-and-screwed and reversed so that it becomes something else entirely.

When you apply these to issues of identity, a number of interesting things happen: it seems to me that subcultures – jazz kids, beatniks, mods, rockers, punks, hackers, nerds – are a form of artificial individuality. This is far from a new position, I know. However, what it seems to be is a sort of cargo cult haecceity. To put it in Hegelian-Kojèvian terms, it might be seen as a shift from animality to snobbery.

World’s best satirical gay rom-com.

I’ve been thinking about this because the popular discourse of American culture during my youth could be seen as imposing a sort of disavowed quiddity on all people: everyone is special. This, of course, was attacked by Chuck Palahniuk in the book Fight Club, which achieved its final form in the film version in 1999: “You are not special. You're not a beautiful and unique snowflake. You're the same decaying organic matter as everything else. We're all part of the same compost heap. We're the all-singing, all-dancing crap of the world.”

Of course, this was simply doubling down: adopting an ironic pose of animality as a new and refined form of snobbery. By being the only people to deny uniqueness and the special status of the individual, they sought to become the ultimate individuals.

But is there something to human beings beyond their memory? Fight Club might prove to be an interesting text here, because its central character (spoilers for a movie old enough to drink and buy cigarettes, and a book that’s old enough to rent a car for that movie to crash and convince itself that the book was driving) is not an individual but a dividual: he is both the nameless protagonist and the raging id that is Tyler Durden with whom that protagonist is involved in an extended campaign of homoerotic mutually assured destruction.

There is also the theory that Marla Singer, played by Helena Bonham Carter, is also an alter of the narrator — which introduces an interesting dynamic to a story that is very obsessed with masculinity and the right way to do it.

Is the protagonist Tyler Durden, or do they simply share a body? In one interpretation haecceity, in the other quiddity. On the one hand, you have a person whose memory doesn’t include things that he himself definitely did; on the other, you have a body stuffed full of minds.

Perhaps it would be worthwhile to move this out of a discussion of media and step into the real world. Let’s talk about Dissociative Identity Disorder and Recovered Memories.

Dissociative Identity Disorder may or may not be real in the sense that the described phenomenon might or might not match the description of the phenomenon. It’s certain that it was a fad diagnosis after the publication of the book Sibyl by Flora Rheta Schreiber in 1973, and especially after the 1976 TV movie (apparently there was a second TV movie in 2007 – though, by that point, the TV movie had lost its cultural cachet.)

What does seem fairly obvious from the history of Dissociative Identity Disorder is that cases of it have been caused by improper treatment: something like 5% of people who receive treatment for it suffer from worsening symptoms, which suggests (to me, at least, I’m not a psychologist) that it is possible.

The motif of the puzzle piece — sometimes imposed on autistic people against their will — is also used for those with DID, at least in fiction. Note the association with the character Crazy Jane from Doom Patrol, which I reviewed a large portion of here.

In cases of Dissociative Identity Disorder, there are at least two “identities” (sometimes called “alters”) present in a patient’s body – how this manifests varies from case to case. Sometimes these alters are aware of one another, sometimes not, sometimes they share control of the body, sometimes not.

What is certain, I feel, is that at times, cases of possession can be attributed to it. However, the exact nature of this condition – its haecceity – remains unclear to me (and, I suspect, to at least some psychologists).

What can be definitively stated not to exist are “recovered memories” as they are described in popular discourse. I know these largely through an exercise I use in my classroom, using moral panics to discuss the importance of critical thinking – my preferred example is the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, presaged by Mike Warnke’s The Satan Seller (1972), and breaking containment with Michelle Remembers (1980). The latter of these describes a series of recollections by a woman known pseudonymously as Michelle Smith – the terminology used (going down stairs, the depths, and so on), is heavily reminiscent of that used in hypnotherapy to recover repressed memories (the podcast You’re Wrong About has a five-part series debunking this. It’s excellent listening, and starts here).

However, the story of “recovered memories” and the satanic panic are closely intertwined. Beyond just Smith’s experience (the fact that she and Pazder married, and that he’s the one to narrate her life in the book, I find highly suspect, to say the least), there’s also the McCuan/Kniffen case, and the later McMartin Preschool Trial. I’ve talked about these moral panics in the past, most recently in mid-March, and my fascination stands, but the issue of memory is heavily intertwined with it: while I’ve expressed a lot of ideas about the ongoing panics, the psychological toll on individual people cannot be discounted.

Remember, there are people who have, essentially, had memories implanted in them. But just as some people will develop an infection when a splinter or other foreign body pierces their skin and others will work it out and heal, not everyone who has been subjected to this will continue to suffer from it. This indicates to me not that there are probabilistic laws about this sort of thing – that A% will believe it for B months or years, and C% will believe it forever and that D% will never believe it, though that quiddity may indeed be present – what this suggests is that the narrative of the self is subject to revision and editing: what I mean is that, while we are – in a very real sense – the stories we tell about ourselves, we are also the author and editor of that story.

Of course, at the risk of shifting from the metaphoric to the pataphoric mode, there’s nothing to stop that author or editor from having a gun put to his head (or take a hammer to the ankle – thanks to Stephen King’s Misery for that one), and have something unintentionally written into it, as is the case with the inserted memories or trauma – on which I wrote a piece a long time ago, but which Saitō Tamaki’s Beautiful Fighting Girl encourages me to revisit. In the Lacanian tradition, trauma is a definite factor, but is not necessarily produced by pain or distress.

Saitō (while Hiroki Azuma’s name, I believe, is rendered in the western order, as per his book, Saitō’s is rendered in the Japanese order as per his), references this in the attitude of Hayao Miyazaki toward a film he saw while young:

Why is Panda and the Magic Serpent a “trauma” for Miyazaki? This is also clear from the ambivalent attitude Miyazaki assumes when discussing this work. As an anime he rejects it as rubbish, while repeating the story of its being a formative experience for him. Isn’t the traumatic nature of this experience inscribed in Miyazaki’s words, “I like this work, but it’s bad”? Miyazaki can keep refusing to acknowledge this work, but he can never, ultimately repudiate it.

Of course, it is true that Miyazaki has not been directly hurt by this experience, nor is he trying to forget it. In other words, there is no “repression” here. Some will claim that for this reason it cannot be considered a trauma, but they would be wrong. The young Miyazaki fell in love with the heroine of this film despite the fact that it was a work of animation. The experience itself may have been like a sweet dream, but he is still plagued by the fact that he had been made to experience pleasure against his will by a fictional construct. The heroine that becomes an object of love at that moment becomes an object of desire, but at the same time, because she is fictional, she also contains already within her the occasion for loss. And the traumatic nature of this experience goes on to manifest itself as a definite, if modest, “split” later in Miyazaki’s career. (p.88, emphasis added.)

A still from Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958)

The phrasing of this, layered as it is in Lacanian terminology, makes it sound as if Saitō is describing the young director being sexually assaulted by an animated character – this is, of course, the danger with a lot of terminology derived from the Freudian tradition (and, as much as people might object, Lacan does come from a Freudian background – he diverged from it, but that was the starting point). What one might say is that it was an object of fascination for him, and that, as a result Miyazaki was hate-watching the film before he determined that he disliked it. Saitō is largely interested in examining the sexuality of Otaku, and seems predisposed to read his sources through that same lens, hence the entirety of the book’s second chapter, “Letter from an Otaku”, which was the most intense and uncomfortable “hey, buddy, what the fuck?” moment I’ve had from a work of cultural criticism.

It is here that I must attempt to stitch everything together. I’m going to risk alienating more readers by referencing yet more anime in the process, but hang on until the end, I’ll alienate the rest of you by bringing in Lyotard. In short, I will reference the quote I often pull from Lyotard and shorten it down to its most representative phrase: “Hang on tight and spit on me.”

The two characters in question — sorry for the low resolution, Paranoia Agent is not as big a presence on the internet as one might think, given Kon’s status as a master.

Questions of identity come up quite a lot in media, and given how quickly Japan seems to have adapted to postmodernism, this is entirely expected. There’s a sequence in episode 3, “Double Lips”, of Paranoia Agent – the one television series that Satoshi Kon, who is responsible for the films Millennium Actress, Perfect Blue, Tokyo Godfathers and Paprika, directed – where a character named Maria is engaged in sex work, hired by a shut-in otaku to perform a sex act (it is not shown explicitly) and after the young man finishes he turns away from the flesh-and-blood woman to ask the plastic figurines in his room if they saw what he did and ask if he did a good job. Maria then leaves, and wakes up the next day as Harumi Chono, a young woman who shares the body with Maria – Harumi uses the body for a portion of the day, Maria uses it for a portion of the night, and they presumably sleep somewhere in there. During the course of the episode, Harumi accepts a marriage proposal, but tries to navigate putting an end to Maria’s nightly forays: in effect, she attempts to kill off Maria and the contradiction between her daylight self and nighttime self intensifies to a point of crisis, at which point the contradiction is forcibly resolved by “Li’l Slugger”, a supernatural entity that seeks out those who have reaches their breaking point and attacks them with a baseball bat.

It is notable that the otaku character reappears later in the series, having retreated into his own mind – but the figurines that fill his apartment, invested with a life of their own, come forward and provide necessary aid to the hero of that episode. The plastic simulacra of women coming to life and serving the role of the “goddess” in a cod hero’s journey (it seems, based on Miyazaki, Kon, and Hideaki Anno, that to be a successful director of anime, one must parody one’s likely fans endlessly).

Apocalyptic visions, like that found in Paranoia Agent, are fairly common in anime. I’m forced to remember that if one were to glue Anno’s Evangelion and Blade Runner together with a glue somehow made out of pure Batman: the Animated Series, one would produce a reasonable approximation of the show Big O, which I referenced previously here. It’s an obvious touchstone for this discussion, given that the relationship of memory and identity is the thematic engine that drives it forward. Unfortunately, the writer, Chiaki J. Konaka (who is also responsible for Gasaraki, a series I enjoy, as well as being involved with Hellsing, Serial Experiments Lain, and Digimon), sometime in the past few years swallowed a pill of a particular color, becoming an ardent proponent of the conspiracy theory “J-Anon”, which is a Japanese variation of Q-Anon, which I’m sure you’re all familiar with – it’s the Stranger Things to the Satanic Panic’s E.T.

Man, I tried to find a picture of what he conceived “Political Correctness” to look like, but everything Digimon looks the same to me, so have the “law enforcement video about satanism” picture again.

Konaka has even inserted this into his work – in 2021, in a special event script he wrote, the villain was “Political Correctness”, described as a threat to the world, and its signature attack was called “Cancel Culture”. The result was, quite clearly, confusion, especially when he claimed that it was not meant to endorse a particular set of political beliefs. It seems fairly obvious from this whole series of events that the stories that we tell ourselves about the world – which include the stories of who we are – can get bent off track, and that, as time goes on, the boundary between what is real and what is fictitious will become even more complicated, as fictions about reality (conspiracy theories) motivate people to create fictions about those conspiracy theories, and these inevitably motivate people to take action in the real world – only for those actions to be, potentially, the subject for conspiracy theories of their own.

This is, honestly, getting quite long, and I’m not entirely sure where it’s going to land, so I will recap and turn to familiar territory.

In the course of this piece, I – a man who hates dichotomies – have discussed two sets of dichotomies: animality and snobbery (that is, adaptation to one’s environment and refusal to accept adaptation to that environment, both of which are variations against humanity, striving against one’s environment), and Haecceity and Quiddity (this-ness and what-ness; individuality and membership in a demographic block). All of this has been to help provide clarification on the central question of my February piece “What is Identity?”, kicked off by an episode of a podcast discussing Blade Runner.

This all was boiled down to the relationship between memory and identity: are they independent, or does the former define the latter? In the pursuit of an answer here, I tried to propose, through the phenomenon of repressed memories and especially the mechanism of “trauma” as identified in a Japanese work of Lacanian critique, that memory and identity form a feedback loop: while memories shape identity, identity can shape memories, and the whole process can be taken off track by traumatic experiences, where our desires about the world contradict themselves.

I have taken to referring to Lyotard as “Johnny-Frank” around the house. Edgar continues to put up with me for some reason.

It is here that I bring up the passage from Lyotard I have referenced a number of times (twice, I’ve quoted it twice) and which I will not re-paste here. The question is why the peasantry became the proletariat: the answer is that they were placed in a double-bind situation, and were motivated by this contradiction of desire: they wanted the old village life; they wanted something new; they wanted the security they had always had; they wanted to be a new kind of person.

There is always something in a human being that desires some measure of destruction. For some people this takes an immediate form. For others, it takes the form of throwing oneself into the long grind of day-to-day life. For still others, it takes the form of desperately trying to escape from the security that grind – supposedly, ostensibly, formerly – offered as a byproduct.

Can the resistance of this self-destructive urge – a vulgar form of the death drive – perhaps also lead to a trauma of its own? Can deciding to keep living, to negotiate with self-annihilation, be just as traumatic as allowing that to happen?

And is this, perhaps, the origin of the “mutilation” that Bookchin noticed in us?

I don’t know. This has gone on far too long and I stopped talking about Blade Runner directly a while back. I’m going to ruminate, but this piece did its job of welding together some concepts and introducing some new ones, so I’m going to chalk it up to a win. Or at least say that it’s done and come back to these ideas later?

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)