Your Desires Have Been Captured: A Discourse on the Mutilated User and the Alienated Worker

[Note: I intended to do a book roundup, myself, but I got carried away on an idea that occurred to me. I decided to run with it because I’m starting up a new job soon, and it seems to me that having a long piece right now would be a good balance to the shorter pieces I’ll probably be putting out soon.]

1.

I first learned about the writings of Murray Bookchin in the context of the breakaway region of Rojava. I failed to take the chance to apply to teach remotely at the University of Rojava last year, and I regret it to this day.

Recently, I’ve been doing a deep reading series on Murray Bookchin’s Ecology of Freedom, and his construction of post-scarcity societies has captured my imagination. To paraphrase how I’ve described it in the past, it is the sort of post-scarcity situation that can be realized without magical technology, as most depictions of post-scarcity societies require.

In science fiction, the archetypal post-scarcity society is the federation from Star Trek: you give a command and ask for a food item or tool, and it can produce it for you from thin air (a perhaps conscious – if only surface-level – inversion of the Marxist maxim that, under capitalism, “all that is solid melts into air”).

Call this supply-side post-scarcity: there is such an abundance that all desires can be met seemingly without effort.

What Bookchin proposes is what could be referred to as “demand-side” post-scarcity: an adjustment not of material conditions but a conscious engagement with desires. It is clear that under late capitalism, our desires are manipulated – the regime of advertising inserts new and alien desires into us, telling us that we need to watch a 47-hour long marvel movie in a theater where we sit in reclining chairs and an ingenious machine fires a Carl's Jr.® Primal Angus Thickburger into our waiting mouths and then we ride home in a Tesla on autopilot to sleep off our meat sweats in an air conditioned room in a house made of foam on a mattress made out of some kind of different foam.

All of these desires were inserted into us by what the Situationist International called the Spectacle. The enervating, all-encompassing discourse that shapes our view of the world. What the Marxists, Lacanians, and certain post-modernists would refer to as “ideology.” Some vulgar leftists would argue that this is a purposefully-constructed illusion of the world. But this Pseudo-Gnostic construction of things – replace the Archons who created the material world with the G20 and you have the basic idea – is oddly optimistic. After all, if you’re plugged into an illusion by some kind of evil genius and must distrust your senses, then there’s the hope that you can rise to the same level of awareness as your captors and fight against them on behalf of the slumbering masses who resist your efforts to free them despite ultimately benefiting from the thankless war you wage in the shadows, you know like in that movie Dark City.

No, we are left with the much more difficult situation of it being nobody’s fault in particular. We managed to arrive at this terrible sequence of events through the Rube-Goldbergian motion of history and disentangling it all will be another long and painful series of negotiations through a variety of means that might produce a better world, but is unlikely to produce a perfect world. Some of these negotiations may be incremental reform, while others might be uprisings and revolts. I’m not talking here about tactics and strategy, but about broad dynamics.

There is no individual solution to the situation we find ourselves in. To say, though, that there are no individual components is a mistake. Every collective action is made up of individual actions: it requires that we all consider our situation and broadly take actions – individually and in coordination – that point in roughly the proper direction.

So let’s turn our eyes back to Bookchin’s demand-side post-scarcity. The problem he points out is that we are not given the freedom to decide how to fill our own needs in our own way. We have particular solutions imposed on us and we are prevented from finding our own.

What he is describing in that passage is a particular approach: trying to free ourselves from the desires that have been inserted into us and figure out what we really want out of life. In short, we have to sever our connection to – or at least minimize the influence of – the spectacle. It requires not only self-knowledge, but also purposeful and considered non-conformity.

Now, back in my youth “conformist” was a dirty word, and it was often used as a pejorative by people who were essentially conformists. This is because conformity is an issue of decision-making, not outcomes. If you deem the vast majority of people to be “the herd” and decide that you’re going to do the opposite of whatever they do, then you’re not a non-conformist: you’re still allowing someone else to make your decisions for you – if you reverse course on the herd, then you’re just a different flavor of the same thing.

Non-conformity requires purposeful and considered actions: and if you decide to go see a marvel movie or sleep in a foam bed after weighing the options, then I disagree with your choices, but I can’t call you a conformist for that.

Of course, there’s a problem with this. Simple non-conformity is very difficult in the face of the spectacle, because it’s all-pervading and totalizing. It appropriates efforts to break it and go against it, and it’s only possible to temporarily do the same thing back to it.

So let’s look at desire itself. Bookchin had no particular theory of desire – but we here at Broken Hands Media have something in our toolkit for just this. Let’s bring Deleuze and Guattari in.

In the Deleuzoguattarian construction of desire, nothing is singular: everything, when you break it down, is made up of an assemblage of smaller parts. Every person is made up of an assemblage of what they refer to as “desiring machines” – they’re not speaking here about a system of wires and wheels, but about a function, instantiated in whatever substrate it happens to be in – that are productive actors. They don’t experience desire, they make desire, which is not a lack but a motive force. When you want something, it isn’t simply because you have some cavity in your soul, it’s because you have a charge that seeks to pull on its equal and opposite charge out there in the world – a delicious meal, a quiet moment in the park, a moment with an attractive person of your preferred gender, a nice thick book by your favorite author – and it pushes you to go out and find it.

I hope you will be patient with me here, because I’m going to leave the discussion of Desiring Machines here, and leave out such concepts as the Body Without Organs and the Full Body of the Earth and the specific types of Desiring Machines. What is important is that desire is a force that motivates us, and it is produced by our subconscious (which reads as a poetic description of how neurologists describe the origins of consciousness).

What Deleuze and Guattari note, though, is that sometimes we possess multiple desires that work at cross purposes. One machine says, “light up a cigarette,” and another says, “quit smoking altogether,” and a third says, “who cares about your health, but take it outside, it’s a filthy habit.” You have this chorus of small and angry godlets handing down commandments that force you simultaneously down mutually exclusive paths.

In this situation, we live under conditions of contradiction – and while contradiction is unpleasant, as the philosophers say, nothing ever died of contradiction.

However, just as you wouldn’t want to press the gas and brake at the same time, living under conditions of contradiction can wear a person out. It can lead to a number of maladies and morbidities that derange our behavior. In the case of the smoker up above, perhaps they switch to organic cigarettes, pipes, or cigars under the impression that they’re less harmful, or to vaping, or they expend their time and energy researching things to imply that smoking is actually good – not because they can convince someone or themselves that it is, but being able to gesture in conversation to the idea that it might be good, even though it’s an idea that is reflexively discarded by any sensible person.

When this happens, you get anxiety and stress. To extend the machinic metaphor here, think of that as waste heat and strain.

Debord is, of course, best known these days as the author of The Society of the Spectacle.

When you factor in not just advertising but the regime of advertising that we currently live under, we pass out of the remit of Deleuze and Guattari and into that of Guy Debord: into the various little desiring machines that form our subconscious, new desires are inserted, and sometimes these simply change the vector of our currently-existing desires. The desire for food becomes, specifically, a desire for a Taco Bell® Crunchwrap Supreme, or some other vaguely food-like object. The nascent desires that begin to take shape in our heads are pushed and prodded into a particular shape before they can wholly emerge.

To frame this in an admittedly hyperbolic fashion: desires no longer emerge from the subconscious and provide a motive force to our conscious minds. Instead, they are imposed from outside. Most of the technological development of the past forty years has been aimed in this direction: each new innovation simply a new way to triangulate and more effectively impose desires on us.

From the side of demand, this is the condition of scarcity. It is not 100% congruent with the regime of advertising, but there is all of advertising is contained within the condition of scarcity.

Let us briefly change focus.

2.

The reverse of the Mutilated User is the Alienated Worker. Not “reverse” as in “opposite,” but “reverse” as in “the other side of the equation”. Every alienated worker is a mutilated user – some people manage to be just a mutilated user, though, because they have enough wealth to free themselves from work. I cannot think of anyone who is neither, or simply an alienated worker (though such individuals no doubt existed in the past).

The alienated worker is the principle figure of Marxist thought. Taking the labor theory of value at its face – and Marx didn’t, but I’m starting from here, so back off – all value was created by mixing the labor of a human being with the natural world to create a commodity. The Capitalist inserts himself as a middleman between the worker and the customer: he constructs the situation so that the worker is paid a wage and the capitalist takes the profit. The worker is, largely, hidden from the customer: there’s no bond of fellowship or goodwill between them. The worker is separated from the fruits of his labor and is thus alienated.

It is this dispossession that adds insult to the injury of such situations as low wages and harsh working conditions: the worker is not esteemed for intellect, strength, or skill, and is treated as an interchangeable part. In the Manifesto of the Communist Party, this is summarized as:

Owing to the extensive use of machinery and to division of labour, the work of the proletarians has lost all individual character, and consequently all charm for the workman. He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him. Hence, the cost of production of a workman is restricted, almost entirely, to the means of subsistence that he requires for his maintenance, and for the propagation of his race. But the price of a commodity, and therefore also of labour, is equal to its cost of production. In proportion, therefore, as the repulsiveness of the work increases, the wage decreases.

[Please note: I’m reading “propagation of his race” to refer to “proletariat”, not some extension of ethnicity or such.]

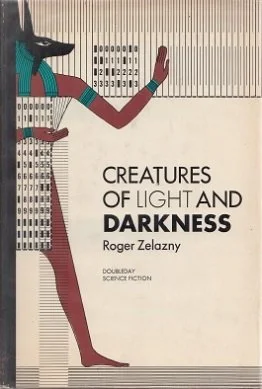

The discussion of the worker as “appendage” to the machine reminds me of Roger Zelazny’s Creatures of Light and Darkness, which featured a philosophical imagining of humanity as the reproductive organs of sentient machines.

But this reduction to being a mere “appendage” of a machine refers to a real feeling, and one that needs to be understood and acknowledged. Being an alienated laborer means being depersonalized and treated as an interchangeable machine part. The regime of labor – much like the regime of advertising – is the cause for this, and while not necessarily designed for this particular purpose, the treatment of workers contribute to this: consider work uniforms and dress codes, the rules about facial hair and presentation. All of them might as well be designed to make workers into interchangeable components.

It must be noted, though, that attempts to address the insult without addressing the injury are simply doomed to fail. It doesn’t matter if your boss pays for a pizza party to thank you for your work if forty hours at your job can’t reliably get you a full stomach and a roof over your head. No amount of gratitude can make up for that particular gap, and one of the biggest, most baffling problems with neoliberalism is the fact that this has been made invisible to the people at the top of the hierarchy.

And why wouldn’t it become unclear: people need money; machines need maintenance. Workers are considered to be somewhere between the two.

3.

And here I return to the Lyotard quote that I encountered years ago in Mark Fisher’s Postcapitalist Desire. It fits in rather nicely, I think:

the English unemployed did not become workers to survive, they – hang on tight and spit on me – enjoyed the hysterical, masochistic, whatever exhaustion is was of hanging on in the mines, in the foundries, in the factories, in hell, they enjoyed it, enjoyed the mad destruction of their organic body which was indeed imposed upon them, they enjoyed the decomposition of their personal identity, the identity that the peasant tradition had constructed for them, enjoyed the dissolution of their families and villages, and enjoyed the new monstrous anonymity of the suburbs and the pubs in the morning and evening. (Libidinal Economy, p. 111)

Jean-François Lyotard, possibly the most perverted of the Foucault-Deleuze-Lyotard-Baudrillard group.

What this quote suggests is that, in the earliest stages of the capitalist reformation – the slow revolt of the merchants against the landed gentry – the working people who had been peasants were dispossessed because they were becoming mutilated users. Sure, many of them were forced into their new lives as industrial proletariat, but it wasn’t simply the enclosure of the commons: it was the insertion of new desires into them.

They did not hunger for the city and its filth, its dangers, its opportunity to engage in sin: they hungered for it because they were given a chance to imagine themselves as its masters. This grift is still quite strong: everyone who stays at a job long enough imagines themselves as the boss, they imagine themselves as the boot instead of the ass. They ignore the fact that not everyone gets to wear the boot. They are drunk on the possibility that they will one day get to purchase a car that costs more than their parent’s house and harm people in their current situation with impunity.

They explicitly want to become the boss. It is my belief that many of these people implicitly understand that they cannot be. They understand that, rationally, it makes no sense to open a restaurant or pour all of your life into a business that will fire you six months before retirement. They aren’t aware that it is possible to want anything other than that. They think that they have to stick with it. That doing so is virtuous.

In this way, people are recruited into their own destruction. The mutilated user becomes the alienated worker to support their consumption habit, and the alienated worker takes these comforts because they sunk all of that time and energy – all of that life – into acquiring it, and they’re too tired to do anything else.

It’s a closed loop.

4.

But the loop is being squeezed tighter and tighter. Work bleeds into consumption and consumption bleeds into work. For many young people, who have been isolated from the professional world, there is this odd brain bug that a job is something that you pick and choose as a product to be consumed. This doesn’t represent a coherent vision of the world, but it represents an aspect of the mutilation that we refer to up above: if someone chooses to be a ditch digger, that means that they chose not to be a CEO; if someone chose to be an auto mechanic, that means that they chose not be a painter; if someone chose to be an insurance adjuster that means that they chose not to be a teacher.

In short, it erases all structural forces and paints over them with the broad brush of “choice.” It makes every accident that befell someone on the way to their eventual course of labor something that was advertised to them, something that they made a rational decision to embrace because it fulfilled their appetites.

In this way, there is a tendency to attempt to subsume the alienated worker into the mutilated user. Some of the strategies to achieve this are, frankly, ridiculous, such as the proposal that people may one day pay for the right to work a job. It is important for us to remember that work is work and consumption is consumption if we are to attempt to transcend both.

5.

And transcension is really necessary – because we can see the maladies that lurk at the end of consumption. Consider Mark Fisher’s writing in Ghosts of My Life on “Party Hauntology,” found in the work of Kanye West and Drake:

A secret sadness lurks behind the 21st century’s forced smile. This sadness concerns hedonism itself, and it’s no surprise that it is in hip-hop – a genre that has become increasingly aligned with consumerist pleasure over the past 20-odd years – that this melancholy has registered most deeply. Drake and Kanye West are both morbidly fixated on exploring the miserable hollowness at the core of super-affluent hedonism. No longer motivated by hip-hop’s drive to conspicuously consume – they long ago acquired anything they could have wanted – Drake and West instead dissolutely cycle through easily available pleasures, feeling a combination of frustration, anger, and self-disgust, aware that something is missing, but unsure exactly what it is. This hedonist’s sadness – a sadness as widespread as it is disavowed – was nowhere better captured than in the doleful way that Drake sings, ‘we threw a party/ yeah, we threw a party,’ on Take Care’s ‘Marvin’s Room’. (p. 93-94; emphasis added.)

An image of how Kanye West — now, legally, “Ye” — goes in public.

The situation of these men – turning to self-destruction in one form or another – is the end-state of the consumption-focused life. When there is nothing more to have, nothing further to fill up the hollowness, you’re left in the same boat that they find themselves in now.

This situation may be on display in West and Drake, but its most advanced forms can be found in the public personae of celebrity billionaires – individuals like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, who seem to be competing not just for the title of world’s richest man, but also for the title of the world’s most divorced man. Because they are unable to maintain healthy relationships, because they are reducing themselves to a kind of hedonistic paperclip maximizer, they put on full display the character of the mutilated user. Their desires are finally their own, not because they have achieved the sort of celebrity-completeness, the mass-media Nirvana, that George Trow talks about in Within the Context of No Context, but because all of their desires have been fulfilled, and yet they must want more. Lacking the artistic output of West and Drake, they are reduced to attempting to commodify and consume space.

Writ small – found in the field of our own lives – this is where we find what Fisher called “Depressive Hedonia”: mechanical pleasure seeking without the actual fulfillment of desire. In Capitalist Realism, Fisher describes this as such:

Many of the teenage students I encountered seemed to be in a state of what I would call depressive hedonia. Depression is usually characterized as a state of anhedonia, but the condition I'm referring to is constituted not by an inability to get pleasure so much as it by an inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure. There is a sense that 'something is missing' - but no appreciation that this mysterious, missing enjoyment can only be accessed beyond the pleasure principle. In large part this is a consequence of students' ambiguous structural position, stranded between their old role as subjects of disciplinary institutions and their new status as consumers of services. In his crucial essay 'Postscript on Societies of Control', Deleuze distinguishes between the disciplinary societies described by Foucault, which were organized around the enclosed spaces of the factory, the school and the prison, and the new control societies, in which all institutions are embedded in a dispersed corporation. (p. 21-22)

This is the result of what he refers to as “reflexive impotence,” and is something that has been observed in animal behavior. It has been noted, for example, that two hyenas – territorial creatures if ever there was anything – will race back and forth along the borders of their territory when they encounter a member of a neighboring pack, but will not cross into the place that is not their territory, and then will eventually settle on digging holes. This is because, unable to decide between options A (fight) and B (flee), they will engage in an unrelated behavior, C.

This is related to the somewhat “democratic” – or, more properly, parliamentary – way that neurons work in concert with one another. If two great blocs are unable to force their will because they are too evenly matched, a third – smaller – one may win out.

To connect this with our previous discussion of advertising and social irrationality, it may perhaps be too pat to say that the irrationality of contemporary Anglo-American society is the result of advertising inserting paradoxic drives into people – they convince you that you want to look good in your swimsuit, shredded like a Hemsworth on the verge of organ failure, but you also want to stuff every empty place in your torso with more and more Wendy's Baconator® burgers, and unable to decide between them, you decide that you’re going to adopt fascistic social beliefs – but it’s also not HIV that people die from directly. Our critical thinking skills weakened by advertising, perhaps these other things can prey upon us like opportunistic infections.

Of course, I’m not stating this full-voiced as my beliefs, I’m saying that it’s a thought that occurs.

6.

The Onion’s response to recent horrors.

But it’s not just advertising, now is it? There are many things that can warp our perspectives about the world and lead to irrational behavior – consider this recent episode of the I Don’t Speak German podcast that examined recent mass shootings in Texas and New York – I vastly prefer to approach these situations second hand, as I dislike directly engaging with texts that this sort of person produces.

Like many people, I’ve been thinking a lot about these recent shootings – but this whole thing hasn’t been building up to a discussion of mass shootings. Instead, I want to talk about the framework I’ve been responding to them in and connect them to the broader conversation I’m trying to have.

In the context of crime – when the person committing the crime is unknown, at least, and leaving aside what counts as a “crime” – generally speaking the three things that must be proven are means, motive and opportunity. The Democrat response to these events is to attack means – to say that we need to ban firearms. This is an understandable response, and one I’m sympathetic to, but it’s not one they’re going to achieve. The Republican response is to attack opportunity – we need more armed men guarding fewer and more secure doors or something. This is, frankly, stupid. They’re using it as a distraction tactic so that nothing is done, because – and remember: a thing is what it does – they are a death cult.

Neither talk about motivation. What series of events happens to lead to the organic emergence of a desire to kill strangers? In the case of the Buffalo shooting, the answer seems to be bog-standard white nationalism: a young man seeking a simple answer for all of his problems is fed a line of fascist bullshit instead of examining the material conditions (he blames his persistent toothache on the actions of a figure he refers to as the “sugar jew”), mixed with some elements of incel thinking. What becomes clear listening to Daniel Harper discuss the manifesto is that there were multiple opportunities to derail the Buffalo shooter, because it seems from looking at his manifesto that, to an extent, he wasn’t completely committed to his course of action, he had simply convinced himself that he had to.

The situation with the Uvalde shooter was much less clear. I don’t have more information on that situation.

However, I find it interesting that no productive discussion is being had on the issue of “why would someone – particularly a young man in American society – want to kill a large group of strangers?”

It must be a particularly American problem. You can look at Switzerland, Israel, Canada, Italy, Finland, and Argentina and see countries with permissive gun laws and fairly high rates of gun ownership, and you will not find the rates of mass shootings that you find in the United States. The problem there isn’t the means, it’s the motive.

This can’t be just advertising: something is pulling at people’s desires and making it so that this sort of result comes out of it.

This connects back into the issue of the mutilated user and alienation in general – if not necessarily the character of the alienated worker. Because we are blind to our history and because a frank assessment of the character of American life is impossible to make, you have people further alienating themselves – the Buffalo shooter willingly cutting himself off from in-person relationships with family, friends, and his cat – and further mutilating themselves – assessing things purely by how much human life they can take – because they are already so far gone that they believe fascistic talking points.

7.

William S. Burroughs entreated us to kill the cop in our heads – to resist the urge toward alienated conformity and consenting to unjust rules – but it’s hard, because so many of us are cast in the role of cops in our day to day life. The shop assistant is made to act as a retail cop; the teacher is made to act as a child cop; the restaurateur is made to act as the food cop.

Because we have a sense of what conformity entails and a script to follow, this leads to the blossoming of what can be called microfascisms: broken or malformed desiring machines that work in a direction best thought of as antisocial and hostile to human life. When the shop assistant kicks someone out who just wants to escape the weather, when the teacher calls a school resource officer on a child, or when a restaurateur puts bleach on discarded food, these are the result of microfascisms on their behaviors.

However, there are also things that run counter to these microfascisms. David Graeber, in Debt, referred to this as “communism” – not in the sense that it derives from Marx’s theories, but in the sense that it fosters community. When asked to pass the salt, you don’t do it because you are beholden to the other person in some vast pecking order, nor do you do it because you are given some payment for your action: you do it because it helps foster a kind of horizontality that some part of you, at least, finds good.

So, am I going to start talking about microanarchisms and microcommunisms to run counter to the microfascism I mention up above? Certainly not, we don’t need to populate our psychology with supersymmetric ideologies the way that the particle physicists seek to double the population of the particle zoo by aiming their particle accelerators right at the Copenhagen interpretation. We just have to recognize that there are tendencies within all of us and, instead of attempting to lay out a psychognomy or a mental atlas, mapping the soul so that it all comes clear, thinking of the human mind as a thing-in-process is more useful.

Better then to think of the mind as a system, like the weather, or the tides, or the slow churning of the Earth beneath our feet. All of us are made up of webs and knots of forces and impulses, some of them reinforcing and some of them antagonizing one another. However, the drives and impulses within us don’t stop at some imagined border of our minds: none of us is a closed system, the way that Saharan dust feeds the vast Amazon rain forest or how the spring rains outside my window were once ocean spray in the Gulf of Mexico.

Here we enter the territory that Deleuze and Guattari explored in much of their work, as well as that mapped by Lyotard in Libidinal Economy. All of them, in that characteristic style of French Philosophers, explain it in abstracted terms, but when you lay it out simply, the message is that to be a person is to have forces within you that interact with one another and push our behaviors in different directions: most of these forces emerge from within us, some of them are passed on to us from outside.

As mentioned above, advertising – and the media in general – are efforts to mass produce these forces within the audience and push them one way or another. I speculate that the conflicts between these forces imposed on us and the native forces of our minds might be the source of some of the morbidities that lead to such problems for contemporary “western” (read: imperial core) societies. This is something that I have referred to in the past as “the epistemic crisis” but might be more productively referred to as “weaponized unreality” or the “conspiratorial milieu.” More specifically, one might see this as the prelude to the above: a snarling or knotting of the forces within us causing an increase in entropy or something like the mis-fold in a protein that gives birth to a microfascism.

It is my hope that this can be fought – at least in part – by recognizing this.

To some extent, this looks a lot like the conclusion of Grant Morrison’s The Filth – his grand, conspiratorial katabasis into and out of paranoia, that concludes with the main character’s body hosting a civilization of sentient nanomachines, each one enlightened and working to live in supportive communion with him and those other people he shares them with. The image of these tiny machines capturing a cancer cell and changing it (not through force but through persuasion) to become a cancer-fighting T-cell sticks with me to this day.

8.

This is all well and good, but how do you do it? It’s fine to say that this sort of thing is what we should strive for, but without some kind of guide or manual, what’s the use? Where do we go from here?

Consider, if you will: I have no fucking clue. I’m not even sure I’ve successfully laid out the problem, and I am very far afield from where I started, but I still feel like the Ariadne’s thread I’ve been looping around behind me is still taut.

Of course, have I done much more than enumerate the problem of desire as Deleuze and Guattari enunciated it? Have I, at any point, stepped from their shadow? I don’t really believe so. But maybe I’ve restated it for my audience in a slightly more digestible fashion.

I dislike most metaphors of the self: a human being is not a machine, they are not a computer, they are nothing of the sort. All of these metaphors are simple models that obscure the real shape of things. But we need metaphors to understand things: Lakoff and Johnson, in their work The Metaphors We Live By made a compelling argument to that effect.

But everything I try feels incomplete.

So let’s try this without metaphors.

No, not that. In all seriousness, though: the above is one of Lacan’s simpler “graphs of desire” and I feel simultaneously like such things are on the verge of being clear and as if there’s something kabbalistic about the whole business.

All of us are a field upon which forces play out. These forces have a character – positive, negative, as we understand them – and have a vector – giving them magnitude and direction. Sometimes these forces jump from one person to another – when we inspire love, hate, disgust, friendship, and frustration – but they also play out within us. Sometimes these run at cross purposes and neutralize or deflect one another.

However, this describes the unconscious. Our conscious minds – in my belief – are able to manipulate these internal, subconscious forces and may help smooth things out if we train ourselves to do so. Now, I don’t necessarily believe it’s possible to live without contradiction (I’ll leave aside whether or not it’s wise to do so for another discussion). However, we can try to minimize the contradiction or shunt these contradictions off to another area of the subconscious or unconscious mind.

I believe that this is a necessary step, because we hope one day to build a better society. Again, something I’ll leave aside: whether to sweep away or reform the current one. However, making a better society demands that we try to be better people.

We have to try to be the sort of people that can live in the world we wish to build.

We also must recognize that the world that exists makes it difficult to do this, and we have to show grace to ourselves and others.

This does not mean overlooking misdeeds, but it does mean trying to help one another be better people without being patronizing or manipulative. It also means trying to make life better for those around you without burning yourself out.

In my understanding, and this may not completely seem to follow what’s been discussed thus far, this leads to what I consider my cardinal ethical rule: not to treat others as I wish to be treated, but – to the best of my ability and self-respect – treating others as they wish to be treated.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)

If you’re interested in reading more about Murray Bookchin and his thinking, and don’t want to wait for me to gather more quotes, you can learn more about the concepts here by visiting the website for the Institute for Social Ecology.