A Close Read of Ecology of Freedom, Part 4

I’m more overworked this semester than I have been in prior semesters, so I decided to return to the well of Murray Bookchin’s Ecology of Freedom, which I have done close readings of previously. Unfortunately, we live under capitalism, and I live in the cheapest apartment I can find, so my ceiling leaked upon the notebook during one of our summer storms.

Luckily, I can still pull some quotes from it, and given that they emerge from Bookchin’s critique of linear thought and instrumentalism, perhaps groping in the darkness will be worthwhile and lead me to places I would not otherwise arrive.

Critics of "irrationality" do not clarify these distinctions by wantonly banishing every subjective experience other than "linear thought" to the realm of the "irrational" or "antirational." Fantasy, art, imagination, illumination, intuition, and inspiration — all are realities in their own right that may well involve bodily responses at levels that have been meticulously closed off to human sensibility by formal canons of thought. This blindness to large areas of experience is not merely the product of formal education; it is the result of an unrelenting training that begins at infancy and carries through the entire length of a lifetime. To polarize one area of sensibility against another may well be evidence of a repressive "irrationality" that is masked by reason, just as "linear thought" appears in the mystical literature under the mask of "irrationality." Freud, in his ineptness in dealing with these issues from his bastion of Victorian biases, is perhaps the most obvious example of a long line of self-appointed inquisitors whose rigid notions of subjectivity reveal a hatred of sensibility as such. This has long ceased to be a light matter. If the Freuds of the late nineteenth century threatened to destroy our dreams, the Kahns, Tofflers, and similar corporate "rationalists" threaten to destroy our futures. (p. 269 – 270)

Bookchin is a fascinating figure in that he and various postmodern thinkers – as I’ve noted in prior close readings – are very close in some ways. Specifically, I see this between him and the French “Gang of Four” (which cuts out Guattari; properly speaking, it should be a “Gang of Five”, but that’s a discussion for another time), who were the luminaries of postmodernism.

I find this largely in his critique of instrumental reason, which is also one of the harder sections for me: it seems to me that pragmatism is a solid philosophy, but in his critiques of it, I find an element that I cannot really reduce, a residue that remains no matter how many times I try to work through this.

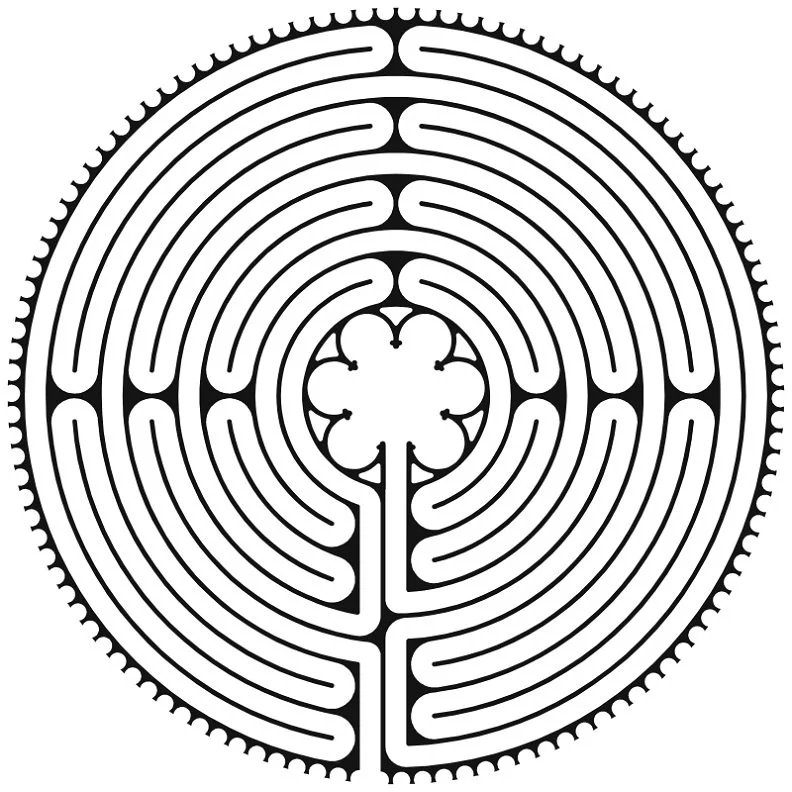

Image uploaded to wikimedia commons by Ssolbergj, and used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

This critique is largely in the fact that he feels that linear thought is too limiting: it locks us into a very constrained pathway. Much like the medieval labyrinths, as much as it twists and turns, it inevitably leads to a particular spot. An argument has been made – indeed, I’ve echoed it – that the World Wars and all of their horrors were the logical outcome of modernity as it was conceived of. When human beings separate themselves from nature, they do not become elevated above it, they unleash a monstrous character that we call rationality. However, this character is anything but rational: it is simply the operation of logic upon the garbage inputs that we’ve tied to it: allow nationalism and religious chauvinism and colonialism and greed to operate, and eventually you have the return of colonial violence to the metropole, which is the definition of fascism.

You do not see this solely in the context of the Europe of the last 250 years – you also find this earlier, in such exercises of violence as the Whiskey Rebellion and the American Civil War.

One can look at the process of “rationalization” that Bookchin found in Freud – who attempted to systematize the unconscious human mind, to map it and provide a Rosetta Stone for it, which disenchanted the dreams of the bourgeois – and which he notes is present in such individuals as Alvin Toffler (of Future Shock fame, and who mentored New Gingrich, the so-called “conservative futurist” and the father of our current partisan gridlock.)

If our fantasies are simply reflections of our subconscious drives, of the things that we want and hunger for, then the horizon of human life is more limited. If these fantasies are not, then to reduce them to mere reflections is a violence (shades of Deleuze and Guattari, who argued that the subconscious is not a theater of representation, but a productive factory, the engine that churns out desire and sets us into motion), and to allow this same violence to be perpetrated upon our future is similarly horrific (perhaps not the violence of a bullet, but a slow cancellation?) and something that must be struggled against.

Not that kind of instrumentality.

The proper course of action would be to try to move beyond mere linear instrumentality.

By contrast, what we commonly regard as reason — more properly, as "reasonable" — is a strictly functional mentality guided by operational standards of logical consistency and pragmatic success. We formulate "reasonable" strategies for enhancing our well-being and chances of survival. Reason, in this sense, is merely a technique for advancing our personal opinions and interests. It is an instrument to efficiently achieve our individual ends, not to define them in the broader light of ethics and the social good. This instrumental reason — or, to use Horkheimer's terms, "subjective reason" (in my view, a very unhappy selection of words) — is validated exclusively by its effectiveness in satisfying the ego's pursuits and responsibilities. It makes no appeal to values, ideals, and goals that are larger than the requirements for effective adaptation to conditions as they exist. Carried beyond the individual to the social realm, instrumental reason "Serves any particular endeavor, good or bad," Horkheimer observes. "It is the tool of all actions of society, but it must not try to set the patterns of social and individual life," which are really established or discarded by the mere preferences of society and the individual. In short, instrumental reason pays tribute not to the speculative mind but merely to pragmatic technique. (p. 270)

Instrumentalism is the bridge between epistemology and ethics – the place where it seems to me Bookchin differs most strongly from his contemporaries across the Atlantic – what is notable here is that Bookchin is saying it shouldn’t be. In instrumentalism, we find a purely pragmatic operation of the mind: achieving the ends we have selected irrationally through the (logically deduced) most effective means. Here I find shades not of the Deleuzoguattarian, but of the Trowvian – referencing, of course, George W.S. Trow, who was the last bourgeois (last conservative) thinker who I think was worth a damn.

Trow wrote that in the “New History” (the age in which demographics guided cultural production), “nothing was judged – only counted” (Within the Context of No Context, p.44), and that in this state “the preferences of a child carried as much weight as the preferences of an adult, so that refining of preferences was subtracted from what it was necessary for a man to learn to do” (ibid) and that the end result was that “the most powerful men were those who most effectively used the power of adult competence to enforce childish agreements” (ibid). This is a much narrower, but more forceful statement of the same thing – related to the concept of the “mutilated user” I’ve run with.

The image of Judgment, from the Rider Waite Deck; as a faculty, perhaps the image of “Justice” would be more applicable, but I still think of this card, with the dead being called back to life and all that has happened being weighed.

Our desires have been captured, in large part because we no longer exercise a faculty of judgment over what we want or don’t want. I would argue that this was a sensible reaction to the puritanical limits we had placed over us, which needlessly harmed those at the fringe of society, propping up racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and many other awful tendencies within our society. The faculty of judgment is used, however, in the selection of means, because there’s only one scale upon which something must be weighed: whether it works of it doesn’t.

If we disavow responsibility, then the calculus becomes even easier. Those externalities are someone else’s problem. In the United States at least, we have canonized into law tools to simplify it yet further, given that private companies are legally required to make a profit for their shareholders. Consider the crumbling infrastructure we have in this country; consider also that, due to how we have set up the laws around utilities, utility companies can only make money on building new infrastructure, meaning that we essentially have given them every incentive and no penalty for allowing, say, a massive power grid to go down in Texas, in what is probably the third or fourth worst example of social murder we’ve experienced on this continent in this decade (god, it’s hard to keep track. It was one of the most well-publicized, though.)

This behavior is rewarded with profit, so those in the same situation are encouraged to do this but bigger and harder. In this way, instrumental reasoning, absent judgment of the goals in question, eclipses other concerns. I would argue that, in large part, it also makes it harder to exercise other faculties.

I must ask: have these young people never seen Mike Judge’s seminal documentary, Office Space, which examined the futility of America’s working culture?

Allow me to bring another example forward: I’m a teacher, and in those times where I ask students why they’re in college, many of them do not say that they wish to learn about a subject, and only some of them express altruistic reasons (one of my students, I will not say any more about them, has begun a research project on water quality in the global periphery, so this is not true of all of my students), but the vast majority say that it is “to get a job”, and they view the attendance of class and the acquisition of knowledge less as a way to grow and expand their horizons, and more as an arcane ritual that one performs in the hope of being granted a materially secure life, and anything that does not obviously contribute to this oftentimes is treated as superfluous, something which they can set aside and ignore.

In this way, instrumentalism is not simply wrong, but it is simultaneously wrong and self-defeating. If the purpose of a college degree is to secure greater material wealth, it is not simply through attendance, but through the acquisition of skills, and not all of these would seem to be applicable or necessary from the start. While questions can be leveled at the health and validity of higher education as an institution in the United States, viewing it as an abstract program of self-improvement seems much better to me than as simply a means to greater material wealth.

By reducing ethics to little more than matters of opinion and taste, instrumentalism has dissolved every moral and ethical constraint over the impending catastrophe that seems to await humanity. Judgments no longer are formed in terms of their intrinsic merits; they are merely matters of public consensus that fluctuate with changing particularistic interests and needs. Having divested the world of its ethical objectivity and reduced reality to an inventory of industrial objects, instrumentalism threatens to keep us from formulating a critical stance toward its own role in the problems it has created. If Odin paid for wisdom with the loss of one eye, we have paid for our powers of control with the loss of both eyes. (p. 273 – 74)

And here we find one of the key differences of Bookchin’s ethics – he still maintains that there are objective ethical standards that one can aspire to meet. While I have my doubts, in the context of what he’s discussing, I feel there is some merit to it: generally speaking, avoiding global catastrophe from environmental collapse is good, though I would argue that, when it comes to things at the small scale, the ethical choice becomes much less clear.

Perhaps it is similar to the divisions between the Einsteinian, Newtonian, and Quantum mechanics in physics. At the extreme upper and extreme lower end of what is conceivable, we find qualitative shifts in the mechanics that govern how the physical world operates. Why should the abstracted world of human reasoning be different?

Of course, there’s a parallel problem that you can see if you observe pop culture without allowing yourself to become engulfed by it: I’ve referred to is as “copization”, but it comes across more as the bureaucratization of shared dreams. The protagonist is no longer the lone rebel seeking to escape from the grips of the bureaucratic institution – while such an individual might be the focal point of the narrative format, because the narrative generally requires the sole protagonist – our protagonist is now the bureaucratic institution seeking to fulfill its mission without constraint. In short, despite the cult of rugged individualism and the noise we make about the free market and capitalism, the actual narratives we tell are fundamentally different.

Frankly, I trust the stories to tell us more about our culture than the declaration of belief that you get from individual people. Here’s the fact of the matter: the only desire an individual person is allowed to have is the service of an organization. Only organizations are allowed to have more nuanced goals. It is sort of like if we tried to find a way of explaining the universe that relied only on Newtonian physics, and we completely ignored the quantum level, or – worse – just imagined it as a game of billiards that was simultaneously lilliputian and infinite in scale.

Needless to say, this level of collectivism would be the holy grail for Soviet-style state bureaucrats, so of course it could only be achieved by their enemies after their demise. As Trashfuture so often declares: modern capitalism is just the Soviet Union but shit and expensive.

This is getting me off into the weeds. Let’s return to the text.

Like Christianity before it, socialism has fostered a dogmatic fanaticism that closed off countless new possibilities — not only to human action but also to human thought and imagination. Science, while less demanding in its attacks upon its own heretics, exhibits an equal degree of fanaticism in its intellectual claims. To defy science's metaphysical, often mystical, presuppositions that are rooted in an eerily passive "matter" and a physical concept of motion is to expose oneself to accusations of metaphysics and mysticism, and to an intellectual persecution that science itself once suffered at the hands of its theological inquisitors. (p. 287)

Here we back off from ethics – I plan on reviewing that section and doing a deeper dive into it on my own time when I have any – and return to the discussion of epistemology. In this spot, Bookchin is discussing the dogmatism that tends to swirl around the sciences (see: the New Atheist movement of the late 1990s and the Aughts) and pushing against it. While there is an attempt, these days, to return a sort of poetic sensibility to the sciences, best exemplified by the works of Randall Munroe (XKCD), and worse exemplified by Neil deGrasse Tyson’s twitter presence, all too often there is a tendency in the sciences to push for a kind of knowledge that tends to first cut phenomena from their context and only later attempt to stitch them back in. Consider the study of butterflies by pinning them under glass, instead of observing them alive.

The Tyson Twitter experience.

Of course, the excesses of the early Victorian men of science are not what contemporary science is being accused of. And, yes, “science” is not a church, but a practice – but isn’t it interesting how the more skilled practitioners of that discipline will often behave as if they have an authority to make formal declarations about the nature of the world? While I’m not necessarily a believer in, say, ghosts or anything, I’m going to go out on a limb and say that indigenous peoples probably have practices of equal value to the sciences as we currently practice them, something which we are only now really beginning to grapple with.

In short, it seems to me that what Bookchin is discussing is, instead, the tendency of the sciences to assume that a matter is settled if they’re not examining it. Consider the fact that certain parts of human anatomy are still being discovered. Consider how many things have been deemed unworthy of scientific inquiry. Consider how much knowledge has been lost as a result.

There is also the fact that “science” – as noted above – is a practice, not a church. Which means that it is practiced by a wide variety of people, and these people tend to be part of organizations with agendas. Far and away, the most common of these agendas are making money – see corporate research. Of course, there is also research at universities, and these are largely driven by a desire to increase the public storehouse of knowledge, but the results you get are largely going to be determined by what questions you ask and how you measure them – certainly facts are still there when you close your eyes, but things that are easy to measure will be noticed long before things that are hard to measure.

All of this is also separate from the meme-ified vision of science that exists on the internet.

There’s also the tendency that theoretical research tends to be underfunded in comparison to applied research – which often means that they’re scraping the bottom of the barrel for applied research. Because theoretical research, by definition, has no immediate monetary benefit. It isn’t pragmatic.

Which, frankly, is wonderful from my point of view – it allows me to circle back around to my original point and create a through line (note: this is a joke about the over reliance on pragmatic and instrumental thinking.)

This is actually the perfect example of the limits of instrumental thinking: it is often self-defeating, in that it exhausts its means, and even if we hold pragmatism to be the chief measure, we cannot remain in the pragmatic mode of thought too long. It is necessary for us to embrace the impractical at times, to step away from out work and look at clouds or seek entertainment. Because, even if completing that work is the purpose of our lives, we cannot pursue it tirelessly and ceaselessly, for the exact reason that our subconscious mind operates on a different time scale from the conscious mind, if we do not give it time to catch up, we will be approaching the task without our full panoply of tools.

And this suggests a further question: if the pragmatic point of view is ubiquitous, but also cannot be maintained constantly, then who are we to say that it is natural, instead of naturalized?

Perhaps, instead, we should give some thought to what we actually value – what we want – and try to pursue that, instead.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)

If you’re interested in reading more about Murray Bookchin and his thinking, and don’t want to wait for me to gather more quotes, you can learn more about the concepts here by visiting the website for the Institute for Social Ecology.