Cameron's Book Round-Up: September 2023

It is now October in Kansas City, the one month that’s enjoyable enough to warrant the other eleven. Unfortunately, this is also a busy time, so my reading has been somewhat light. Still, I walk to work and with my headphones in I can power through some audiobooks fairly quickly. Links go to Bookshop.org where possible.

※

Infomocracy (Centenal #1) by Malka Ann Older

The closest thing you’re likely going to get to a post-cyberpunk take on All the President’s Men or similar, dealing as it does with election dynamics in a not-quite-utopian future world state of sorts. It deals heavily with the dynamics of “microdemocracy” — each 100,000 people make up a “centenal”, which votes for one of a number of potential governments to rule over them. The brass ring in this system is a “supermajority” — a government with enough centenals backing it becomes a sort of legislative world hegemon for the next decade.

Needless to say, there’s a lot of things to keep track of to keep everything above board. Enter Information, a sort of non-profit hybrid of Google, the part of the UN that monitors elections, and the Associated Press. They don’t wield power, but they work to ensure the sanctity of the elections and the relative symmetry of information across the world.

It was a fine enough book. I might pick up the followups, but it didn’t grip me the way that some recent-ish science fiction has grabbed me (see: Glasshouse in my last round-up.)

Raw Dog: The Naked Truth About Hot Dogs by Jamie Loftus

An early and strong contender in the nonfiction category, Loftus is a comedian that I’ve encountered as a regular guest on some podcasts I listen to (and who has done some rather amazing short-form podcasts, notably the Lolita Podcast about the cultural impact of Nabokov’s book, My Year in MENSA about her time as the most hated member of the titular organization, and Ghost Church about Spiritualism in both it’s 19th century and contemporary forms.) She is an excellent writer and a quite amazing cultural critic.

Given her history of taking subjects that seem a bit limp to me — Lolita, MENSA, spiritualism — and making them absolutely fascinating, I was tentatively excited to get this book from the library, and I jumped directly into it as soon as my hold came due. It did not disappoint.

The book is, ostensibly, about the history and current manifestation of the hotdog. Under the surface, Loftus tells the story of going on a road trip with a boyfriend who she’s fairly certain she’s not going to remain attached to for the duration of their mid-pandemic meat-tube odyssey to tour a number of famous hotdog stands and get their history while also intending to stop back at her family home in Boston to take care of her father as he recovers from lung-cancer related treatment. There’s a lot there and it’s all rendered in a fascinating comic style that shows an incredible degree of skill.

Side note: I was not an emotionally stable person when I went through college. I can’t help but side-eye anyone who thinks that they were (as a college-level English instructor, I have Evidence that I am legally prohibited from sharing with you. Trust that it exists.) This book has nothing to do with college, but there’s this wonderful coming-apart-at-the-seamsedness to the whole thing, where the author is trying very, very hard to complete a somewhat intricate intellectual task while in an impossible situation emotionally.

Also, you learn a lot more about hot dogs, America’s favorite cylinder of meat, from a very funny writer.

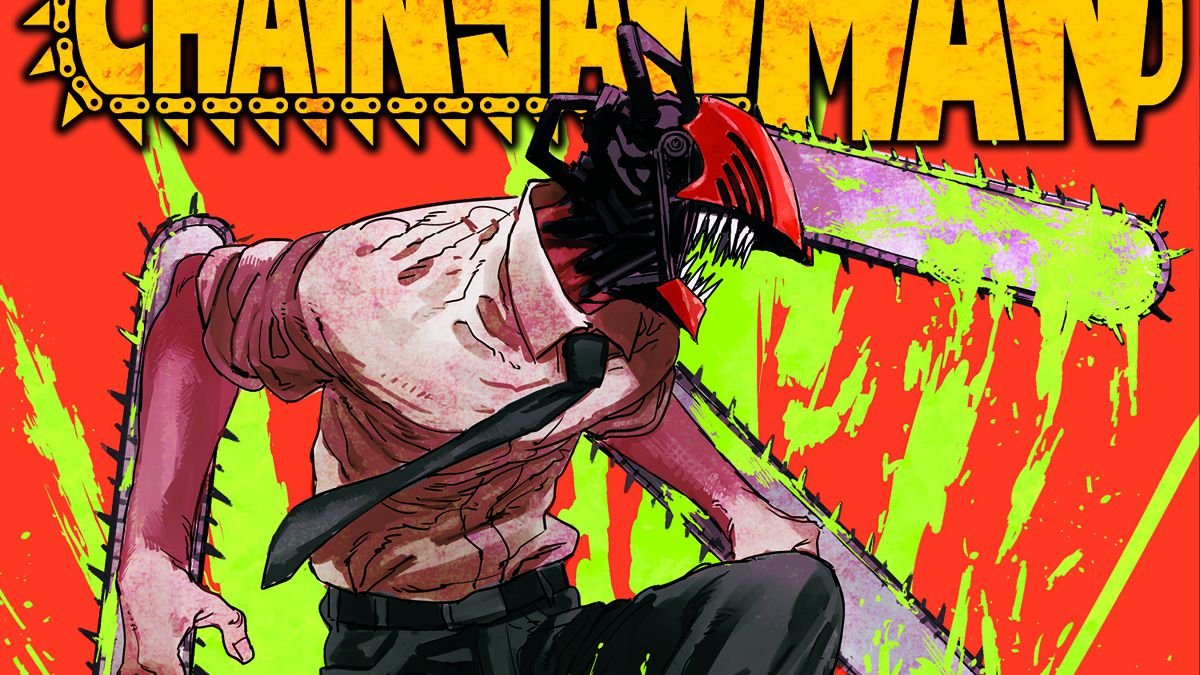

Chainsaw Man Volumes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 by Tatsuki Fujimoto

The anime of this series was one of our favorite television shows of 2022. It takes place in a world where human fear is the food and drink of creatures commonly called “devils”, which take on the characteristics of the fear that powers them. Rare fears generate weak devils, stronger fears generate stronger ones. The main character of this story, Denji — an oafish Japanese teenager forced to labor to pay off his dead father’s debts to the Yakuza — hunts them with the help of his partner, Pochita, a dog-like devil with a chainsaw blade growing out of its face.

After an incident involving a fairly powerful devil, Denji is killed and dismembered. Pochita sacrificed himself to restore Denji’s life, and — consequently — allows Denji to transform into a monstrous being: the eponymous Chainsaw Man.

That’s the first chapter or so. If you’re familiar with the anime, it covers roughly the first four volumes of the comic, with a bit of extra material. I might characterize its genre as a sort of “Post-Shonen” — it takes many cues from earlier comics aimed at an adolescent male audience (I’d invite anyone well-versed in the corpus to compare it to Go Nagai’s classic Devilman, revived by Netflix in the past couple of years into the nauseating and psychedelic Devilman Crybaby) but takes them seriously in a way that is unusual for the genre. It uses the same tropes, but it’s organized by a distinct logic that seems as if it would be much more at home in an early Quentin Tarantino or Coen brother’s movie (indeed, if you watch the opening to the anime, you can see, over Kenshi Yonezu’s…J-Ska?…opening song, sequences clearly mirroring Reservoir Dogs, The Big Lebowski, No Country for Old Men, and Pulp Fiction can be seen.) I would suggest that this represents a maturation of the genre, though along different routes than ONE’s Mob Psycho 100 (as written about by Sam Keeper on the old Storming the Ivory Tower website, now sadly defunct, it seems.)

Expect more on this as I read more of it. I’m less than halfway into it, and I’m going to end it here.

Edition pictured from Penguin Random House, illustrated by Lilli Carre.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

I don’t really consider a meal to be a meal if there’s no vegetable component, and I’d been reading a lot of junk food up to now (some of it enriching) and I thought I would revisit a book I read back in high school, but I didn’t want to subject myself to a nineteenth reading of The Great Gatsby , a book that has no redeeming qualities, so I thought I’d revisit a classic that I didn’t have thoughts one way or another on but which a lot of people hate.

This is the second novel in a series, and I’ve never read the Adventures of Tom Sawyer. I don’t imagine I ever will. However, this book is one that I was assigned back in high school, so I was broadly familiar with it. The principle memory most people have of this book is the near ever-present usage of a particular slur to refer to black people. I’m not going to repeat it here, and I have to admit that I felt a great deal of discomfort listening to the audio book of this, with its clearly white reader.

However, dear reader, I think that’s the point of the whole exercise. People object to this book on the grounds of its language, but don’t acknowledge any bit of what’s in the plot or the evolution of its central character.

Consider: Huck is a young boy who’s been taught that slavery is dictated by God as part of the way of the world. He lives in a racist society, and he has soaked up many of its ideas about how the world works.

However, once he’s escaped from his abusive father and the strangling, overbearing care of the women who had taken him in, he finds himself with no company on his journey save Jim, a runaway slave. The two of them spend time together and work together and rely on each other. The whole time, Huck is horrified at what he’s doing: he’s stealing. He’s enabling a contravention of what he sees as the natural order. But, despite all of this, he comes to see Jim as a person. Eventually, Jim is recaptured and Huck is left with a decision: allow Jim to remain captive, or damn himself by helping Jim escape.

And he realizes that he’s never had anyone care for him or rely on him as much as Jim, and this leads to the key of the whole book, the statement that “all right, then, I’ll go to hell.” Even if it contravenes God’s will, he intends to do what — to him — seems to be the right thing (though, funnily enough, he acts as if he’s resolved to do some horrible crime.)

In all honesty, everything after that needed a bit of work. Mark Twain, fundamentally, should have shortened everything he did by about 20% and it would have been twice as good.

I’m not sure, however, that it should be assigned reading in schools (don’t get me wrong, I’m not advocating it being banned), but I do think that it would be better something young people are exposed to by parents and family members than something made into the object of classroom discussion, because that so often turns into a debate about the language, and there’s always that one kid that just really wants to say slurs.

Mister Magic by Kiersten White

I’ve talked previously about the influence Homestuck is having on contemporary culture (See my writing on The Locked Tomb here,) with Mister Magic, we have the first example of another internet phenomenon influencing literature. Notably, here, creepypasta (which has been subject of discussion here recently and not so recently). White draws, most specifically, on Kris Straub’s Candle Cove story, being a novel about a children’s show that only kind of existed in the fictional world of the novel.

The central character of the story is Val, a woman in her early thirties that works on a ranch in Idaho. She’s lived there as long as she can remember, and has followed — religiously — the rules that her father gave her about being careful when speaking to strangers and not watching television. Even after he developed dementia, she still followed them. However, certain things were just not really on the table for her: she had no identification, and had never driven a car, and she had a number of scars that made it look as if she had been burned at one point. She figures that they’re on the run, but she never got a straight answer out of her dad before he started losing touch with reality.

After her father died, a small group of young men — Isaac, Javier, and Marcus — approach her and tell her that the four of them — along with one then-absent person, Jenny — were five-sixths of the “Circle of Friends” from the TV show “Mister Magic”. They were child stars, and Val had been their headstrong leader before she vanished. They were all traveling to a reunion show and had seen the notice of her father’s funeral.

They invite her to come along.

Clearly, things go off the rails.

Okay — that’s a lot of material to sum up perhaps the first fifteen or twenty percent of the book. The earlier portions are great, and I think there’s a lot ot recommend the back half, but it certainly declined in quality as time went on. My feelings on the matter can be boiled down to the fact that simply too much information was revealed and the whole thing became a bit too elaborate. Sort of a hat on a hat situation.

I think that there will, one day, be several great novels inspired by so-called creepypasta. I think this one will go down in memory as the first, but not as the strongest among them.

The History of Magic: From Alchemy to Witchcraft, from the Ice Age to the Present by Chris Gosden

Another strong nonfiction contender — Gosden is an archaeologist specializing in a field called the “archaeology of identity”, and focusing on the construction of the English identity (but I’m not going to hold that against him.) He takes a broad-ranging approach to his subject, somewhat similar to Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything (reviewed here), but focused less on political formations than on the concept of Magic, which he contends is alive and well (not simply, he notes, in neopagan circles. Everyone, he contends, has magical beliefs.)

His survey of material begins in the paleolithic and extends to the present, looking at the evidence of magical beliefs in prior eras and advocating that they represent key elements of a worldview. One of the segments that I most enjoyed was his brief history of the Siberian Shaman: far from being an ancient figure, he argues that the archaeological record suggests that the Shaman is a contemporary one, an epistemological freedom fighter resisting the eastward expansion of the Russian empire. This is another key comparison between Gosden and the Graeber/Wengrow team: he maintains that the cultures that we see in the achaeological and textual record are dynamic, changing things, and that people engage in innovation and alteration of their ideas about the world and their beliefs — not simply technologically or artistically, but magically, as well.

His construction of the discourse between science, religion, and magic as a “triple helix” is interesting, I believe, but I also think that he does himself a disservice by cutting out philosophy and art, which seem (to me) to be operating on a similar level.

Still, highly worth reading. Strongly recommended.

They don’t make book covers like they used to, do they?

The October Country by Ray Bradbury

A collection of short stories from an American master. Many people think of him as a science fiction writer, after Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, but I’d argue — based on this book and Something Wicked this Way Comes, that he’s a horror or fantasy author closer in character to an early Stephen King. There’s a similar strain of horror Americana that people forget about: like the scenes that Norman Rockwell painted, but under a cursed moon and crossed by a cold wind.

As with most things autumnal, there’s an element of nostalgia to the whole affair — I believe that’s outside of myself, though I can’t be entirely certain. Still, it’s interesting that this sort of aesthetic feel isn’t more widely emulated by active writers.

The stories in this collection are, admittedly, showing their age, but there’s a certain macabre quality to them that can’t really be easily found anymore, a subversion of the mid-century prosperity that surrounded him and we all struggle to believe was ever really real.

The strongest of these, I believe, are “The Skeleton” and “The Emissary”, though I’d say that they’re all at least worth reading. You can read the latter of them — it’s fairly short — on the Library of America page, here. At only eight pages, I think it’s worth it.

The Silmarillion by J.R.R. Tolkien

Where to start with the Silmarillion? If I were a man like it’s author, I’d suggest “at the beginning” is the best answer, but I’m not completely sure. It’s a difficult, obscure book, one that invites comparisons to the Old Testament, Beowulf, and the Homeric epics, though I’m not sure it’s one for general consumption — there’s a reason that Tolkien didn’t present it during his life: it wasn’t a complete story. The manuscript was fixed up by his son, Christopher, and fantasy author Guy Gavriel Kay, but they do a fairly good job of keeping the original style.

The hard part is that, despite the story being well-drawn from its source material, it’s just not presented in a way that’s easy to get through.

If you’re a completionist who’s in to Tolkien, I’d say go for it. If you’re not, skipping it might be a better course. In either case, I’ll probably read The Children of Húrin at some point, though I think I need to take a break from fantasy epics for a bit.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron (Bluesky link; not much there yet) and Edgar (Bluesky link). Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.

Also, Edgar has a short story in the anthology Bound In Flesh, you can read our announcement here, or buy the book here