Analog Horror and Nostalgia

I’m really pleased by the response that my piece from last week, reviewing Public Access, received — it’s a great game, and I was excited about it the moment that I learned about it. This is partially because it deals heavily with some themes that I’ve been reading on for years.

In the lead-up to running it, I made a point to revisit one or two key texts on it, and I thought I’d gather those into a more coherent theory of Analog Horror this week. If you’re not a TTRPG enthusiast, don’t worry — this is going to be more in line with our explainer posts that are normally aimed at philosophical topics.

※

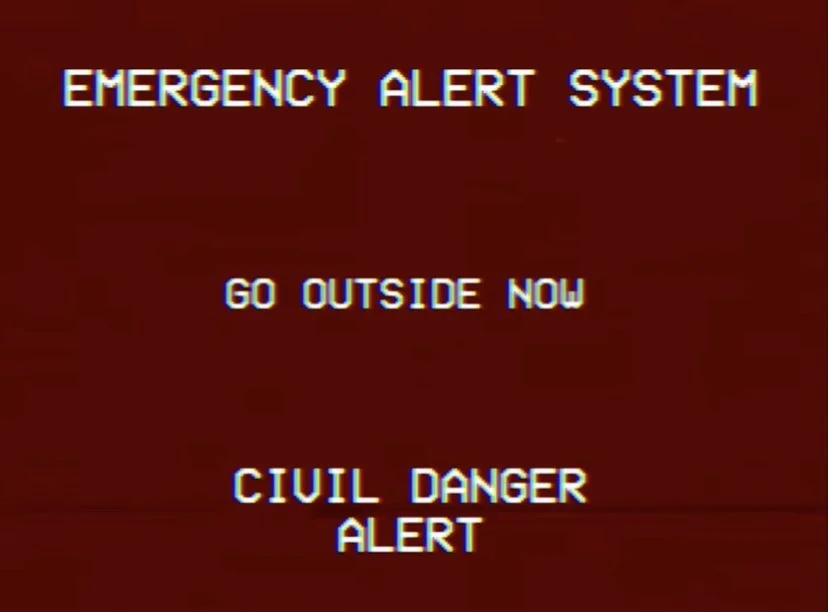

Image from Kris Straub’s Local 58, possibly the first self-described piece of Analog Horror. Straub previously created Candle Cove, which may be the most famous “creepypasta” of all time.

What Is Analog Horror?

Okay, so, full disclosure: while I’m normally a teacher, I do also occasionally do some typesetting for an online magazine based out of the UK. So I do habitually slip into Britishisms and archaicisms and, as a result, I’ve occasionally rendered this term as “analogue horror”. So sue me.

The fundamental idea of analog horror is found in a feeling of hauntedness that clings to abandoned and archaic technology, generally (but not always) those related to the distribution of media, such as recording or broadcast equipment.. This is related to something that I discussed with the students in my literature class last semester when I showed them a story from Stefan Grabiński’s The Dark Domain, “The Motion Demon” about a haunted train — possibly the first example of such. While, now, the idea of a ghostly steam engine is nothing to bat an eye at, Grabiński wrote the story in 1919, and the first rail line in his homeland of Poland (then part of the Russian Empire) was operational in 1845. That’s a 74 year gap. Is that the amount of time that needs to pass for something to be entrenched in the culture enough that it is coherent to say that it feels “haunted”?

This is all just restating things from my prior piece — “A Spectrum of Haunting” — but it feels pertinent to point out that, at some point, things flip over from being ridiculous and start feeling as plausible as the rest of the genre.

Let’s take a look at a particular example. Allow me to direct your attention to Oxenfree.

Oxenfree — and its sequel, subtitled Lost Signals — is an adventure game that deals with exploring an empty island in the Pacific Northwest over the course of a summer night. Something happens, and the teenagers (or, in the latter game, twenty-something part-time researchers) get sucked into a dangerous contest of sorts where a ghostly entity or entities (called, later “The Drowned”) attempt to hijack their bodies to escape from the hell dimension that they are stuck in. Fairly standard horror movie set up. Nice flair of northwestern gothic, good little nautical touch — who doesn’t love a light house? — but it becomes Analog Horror in the tools you use to confront it — see the screenshot above. Look closely: your primary tool here is a radio. You cause supernatural effects by tuning into them. Later in the game, you unlock a radio with a wider band, allowing you to tune into new frequencies that were previously inaccessible. This is the same as in one of those old Legend of Zelda games where you unlock the hookshot or eye of truth: it’s a powerful ability that you can use to change the way the game plays.

But it’s a radio, of the sort your dad might have listened to a baseball game on at some point, because to the people that might play this game, that is largely a decontextualized piece of technology. So why not recast it as a potential means of contacting the other side?

Of course, this is but one example — a good one, but fairly standard in its approach. We could reach much earlier:

Poltergeist came out in 1982, and the first CRT image was in 1911 — which might suggest that there’s something to the 70-year number that Grabiński’s story suggests. In this film, the static-filled television screen becomes a portal to “The Other Side”, and the daughter of the haunted family gets sucked through. It’s a classic haunting movie, and it’s actually something that I referenced previously in a piece on a relevant idea, namely that it seems like our ideas about spirit and matter have flipped after howevermany thousands of years, and I would attribute this to computation: it’s hard to think of the immaterial as sexy and fascinating when our immaterial world consists mostly of spreadsheets, scams, and popup ads, and it’s much easier to romanticize vinyl records and hand-made objects. I called this “the new dualism” in there, because it really seemed that it was an interesting reformulation.

※

Sidenote: The Grabiński Period

I’ll be honest about a research failure: I wasn’t expecting the 70-year time frame to crop up twice. Let’s call this the Grabiński Period for ease. If this idea was true, then we could formulate it as “about seventy years after a cultural artifact appears, you begin to see it depicted as a locus of haunting.” So we could expect to see radio-related hauntings appear around the 1960s, because its earliest forms were proven viable in the 1890s — and the earliest example I can find is from about 1971 (Richard Matheson’s Hell House.)

So that’s three examples. Properly speaking, this suggests that Analog Horror is coming too soon. While my example up above didn’t properly use them, the totemic item for analog horror is the VHS tape, which shouldn’t gain haunted status until sometime around or shortly after 2046.

This would be the case if we took a technic understanding of this period. What does the seventy years actually signify? Let’s say that it takes forty years for a technology or other artifact to be introduced and become widespread (looking at television) and then another thirty for people to grow up with it, become artists, feel nostalgia for the early days, and then for them to pull out something uncanny from that nostalgia to make horror with.

In short, it’s not that it takes seventy years, it’s that it’s the spooky twin of the Gartner Hype Cycle.

Uploaded by Jeremykemp and used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Once something is widespread, it can become the object of nostalgia. Once something is the object of nostalgia, it’s easy enough to flip the switch into something uncanny.

Emotions that in prior times might have been evoked by colonial-era imagery and autumn landscapes now cling to the electromechanical systems of our youth. For me, it’s payphones that evoke these feelings, but for others it’s the VHS tape.

This is explicitly a function of nostalgia, but it is nostalgia had second-hand, where the original object is eerily absent, decontextualized and beginning to run down like William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops, where the original recordings were physically destroyed in the process of transferring them over.

What we have is something from which the human mask has begun to slip, become strange. That’s what the Grabiński Period is: the time it takes for the familiarity to slip from something clearly made by human hands — or near enough — for the everyday to turn into something eerie.

To quote Mark Fisher:

Behind all of the manifestations of the eerie, the central enigma at its core is the problem of agency. In the case of the failure of absence, the question concerns the existence of agency as such. Is there a deliberative agent here at all? Are we being watched by an entity that has not yet revealed itself? In the case of the failure of presence, the question concerns the particular nature of the agent at work. We know that Stonehenge has been erected, so the questions of whether there was an agent behind its construction or not does not arise; what we have to reckon with are the traces of a departed agent whose purposes are unknown. (The Weird and the Eerie, 62 — 63, emphasis added)

In short, the Grabiński Period is the time it takes the apparent agent to depart, and their purposes to become unknown. With analog recording technology — video casettes, sound and film reels — that period was artificially shortened by the emergence of new recording media.

※

A Message From the Babbling Corpse

I would be remiss if I didn’t bring in Grafton Tanner, whose Babbling Corpse: Vaporwave and the Commodification of Ghosts I specifically made a point of revisiting earlier this year. Tanner is a much more capable writer than I, and his Babbling Corpse is possibly one of the more competent post-Fisherian offerings from Zero Books.

In Chapter 1 of this short book, he opens by glossing scholar Jeffrey Sconce:

In Tobe Hooper’s 1982 horror blockbuster, Poltergeist, malevolent ghosts enter a suburban family’s home through the television set and kidnap their daughter, all while ransacking the house and upending their lives. The film has remained a canonical, mainstream fixture of the horror genre since the 1980s and seems to advance a heavy-handed anti-TV argument: that the television is a medium of horrors. For viewers of the time, Poltergeist allegorized the rampant, media-fueled fears of the Reagan-era nuclear family – namely threats against children, such as kidnapping and even ritualistic Satanism. The film is literal in its representation of outside forces entering the safe enclosure of the suburban home and corrupting the balance of family life, and the conduit through which the ghosts enter is the television – the “medium of the dead” (his italics). What happens in the Freelings’ home takes the 1980s fear of television’s near-spiritual power and uncanny presence to its frightening conclusion. Poltergeist’s ability to tap into a cultural mistrust of electronic media has afforded its timelessness, such that a remake was released in mid-2015 (appropriately updating the story to fit with our current screen-saturated environment).

Perhaps no other book more accurately details the history of electronic media’s relationship with the occult, from contacting the dead via the radio to fearing the televisions in our homes, than Jeffrey Sconce’s Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television, which posits that we have often thought of electronic media as “gateways to electronic otherworlds.” Beginning with the invention of telegraphy and the rise of Spiritualism, Sconce outlines the history of electronic media’s uncanny ability to appear “haunted.” In particular, “sighted” media (such as the television) foreground this uncanniness because the “‘ghosts’ of television…[seem] to actually reside within the technology” – ghosts in the televisual machine, if you will.

This proposes an alternative to the gradual progression of media from ubiquitous to nostalgicized to haunted, instead proposing that there has always been something ghostly about the electrical — and there was certainly a lot of discourse around the turn of the last century (from the 19th to the 20th, I mean) that suggested that people believed that they had captured the fire of the gods in a Promethean coup.

The best (literary) example I can think of this is in the novella The Edge of Running Water by William Milligan Sloane, III — an early cosmic horror story about an electric apparatus for seances. And how is this any more eerie than the sequence in episode one of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, where a home video of Laura Palmer is used to identify the fact that she had been in a secret relationship with a motorcyclist? How is that different from contacting a ghost to hear its secrets revealed?

As Tanner argues, there is always something haunting about electronic media. It is always present in our lives and, indeed, seems to slide into the background all too easily He describes this process as “vaporization” — the third step in a process that music critic and philosopher Simon Reynolds laid out that begins with “reification” (making into a thing) and “liquefaction”. To these two, Tanner argues we need to add

a third step in this process – vaporization. Music transforms from a “thing” into a stream and then finally into a formless cloud that infiltrates our everyday. This is different from the piped-in Muzak of prior decades. Vaporized music is the music of PR, the sound of ephemeral, hollow music. It is music you encounter, not music you listen to – in Internet advertisements, in clubs and bars, in grocery stores and malls. It is not meant to soothe you or to help you perform better at your day job or to necessarily sell you something. This is the sound of hype, of constant streams of music criticism evaluating albums and posting their declaration of worth within days of release. The vaporization of music makes it easier to sell of course, but the goal is to shape public opinion. With social-media sites and mainstream music outlets parroting one another’s opinions, there is no longer any room for a differing opinion. Either you subscribe to the monolithic opinion of a hyped band or you are simply a contrarian, and the best part is you don’t even have to listen to the music being discussed to join the chorus of prevailing opinions.

And this gets to the next part of the equation — it doesn’t matter if technology needs to sit on a shelf for a time before we can call it haunted or if electronic media rolls off the assembly line that way. What matters is how people think about it.

To borrow from Colin Dickey’s Ghostland (which we both loved), why do we want it to be haunted?

※

A New Dark Age

In The Call of Cthulhu, Lovecraft mentioned that human beings, were they able to correlate all of their knowledge go mad or flee into the safety of a new dark age. With all due respect, which is little, we’re already there — as Charles Stross conjectured in Glasshouse (reviewed here), our attitude towards storage media is leading us into a situation where we will be unable to access things stored previously. Think about how many cultural artifacts have just been lost. Now understand that we are doing this to ourselves.

This, I believe, is a partial explanation for the popularity of analog horror — there is the sense that we have all have not just been sleepwalking into a dark age, but that without realizing it we’ve become so adapted to it that we might not be able to survive the sort of cultural transition that would be necessary to turn into the skid and fix it. The cause of this is capitalism, because companies want to protect their proprietary data — and anything that ends up on one of their machines is proprietary.

In short, how can we not lose something precious when the way we store media changes every five years? What began as a money-making strategy has become a caustic force upon our collective remembering — something that I believe contributes to the (potentially erroneous) sense that “progress is speeding up”. To which I would reply that there seems a much greater degree of change previously: at the start of the 19th century, no person had ever moved over land faster than by horse, then, by the middle of that century we had the railroad. A similar period of time later, we had the airplane, and the same amount of time again gave us the moon landing — three human lifespans from horseback to the moon. Now, we struggle to return.

Frederick Jameson said that “it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”, but I think that’s because — for a lot of people — the two are the same thing, or are so entangled they might as well be. For them it’s like imagining the end of depth or blue or the twenty-four-hour day. Now imagine living in a situation where the long term survival of culture (not to mention, you know, survival) requires ending one or more of those things.

These anxieties cannot be dispelled — so they become sublimated. I believe that other sublimated anxieties are wrapped up in this same general phenomenon, producing things that lack the explicit form of analog horror but possess enough of a genetic resemblance to it to be recognizably the same general kind of thing.

※

Frontier, Fragility, and the Backrooms

Honestly, this next part could be all its own piece, I think, but I’m reluctant to put in the legwork to really do a deep dive into the Backrooms, which originated on — sigh — 4chan’s /X/ Board, which is their creepy/occult section. For reasons obvious to the internet-savvy, I will not be linking to the board, but I can point to the video that popularized it, produced by Kane Pixels (real name Kane Parsons).

The Backrooms lacks the emphasis on recording and broadcasting — old forms of media distribution — that tend to characterize analog horror, though there is the implication in the Kane Pixels video that he is recording it on a physical medium. This is similar to the connection between the genre and the movie Skinamarink, though I’m not going to dive into that one beyond saying that film grain was intentionally added to that film after the fact, implying a desired connection.

If I am correct and the analog horror genre is connected to the anxieties about lost knowledge caused by the rapid supercession of recording media, then the backrooms stems from a similar but distinct fount. Consider: Capitalism always needs an outside to extract value from. Far from there never being any such thing as a free lunch, Capitalism can’t make ends meet enough to survive without a free lunch — right now, it’s the arbitrage of extracting and producing in the global periphery and shipping everything to the imperial core. I do not believe that even the capitalist ideologues want this to be the case: this is where dreams of space colonization come from. If we move the frontier out into space, then all of Earth will be the imperial core — problem solved!

But we can’t even get back to the moon. Maybe long-term space travel is an impossibility for human beings.

Given these constraints, and given the fact that for many of us “capitalism” means “financial capitalism,” what would a physical frontier look like?

Probably an abandoned, endlessly repeating office space, of the sort that we see in media but so few of us actually experience. There’s probably some third-hand anxiety about the anticipated corporate real estate crash, which will bookend the decade or so of culturally lost time started by the 2008 recession — brought on because we hit pause in the middle of the 2008 crash by lowering interest rates but supposedly can’t any more after the pandemic — but that’s just another angle on it: why not imagine an unreal space if you’ve lived your entire life in unreal time?

In 2025, the first of my students born during that financial crisis will enter my classroom. Many of my students, despite technically being born before it, can’t remember the period of time before 2008. For them, this has always been the case. This weird, amnesiac, futureless always-now that has been given to them.

Why would it not feel unreal? Why would you not want to find something hidden and lost that might explain it, even if you don’t know to describe it as such? Why would you not fear unlocking some horrible destructive force that had been sealed away previously, when that’s exactly what created the very world that created you?

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)