The Future of Higher Education Looks Dark

Despite being an educator, you might notice that I don’t discuss education much on this site. Part of this is simply my attempt to put up a wall between my professional life and my public speech – I intend to drill a hole in this wall today, though I’m going to maintain a bit of privacy. I won’t be publicly naming the school(s) I teach at, for example.

The reason I decided to write on this subject is quite simple: I’m pretty sure that the American College system is in a state of collapse. Now, I admit an intellectual tendency towards catastrophization, but I don’t think I’m alone here. I think that this is clear to anyone who has a passing familiarity with how things are going right now.

A lot of this makes me think about this one scene from the movie Real Genius (1985). Fundamentally, it’s a matter of the human element being thrown aside.

I’m going to start with the particular and move out into the general here. A quick survey of my own classes, those of my colleagues, and those of my friends and acquaintances who teach at other schools shows a pronounced decline in attendance through Spring 2021. Fall 2020 was, for me, a banner semester of high attendance and high marks, but I think this may have been a statistical anomaly. There’s good reason to think this way: first semester Freshmen generally jump directly to the classes they are confident in, while second semester is reserved for classes they are less enthusiastic about, it seems.

But a decline in attendance will result in a decline in funding: even if students are enrolled and simply not attending, this will result in the dreaded phenomenon of “reshuffling” where less-attended classes are canceled or folded into other classes, with attendant changes in faculty pay and student outcomes.

…life imitates art. Tweet from Aaron “Loose Legs” Ansuini, reading: “HI EXCUSE ME, I just found out the the prof for this online course I’m taking *died in 2019* and he’s technically still giving classes since he’s *literally my prof for this course* and I’m learning from lectures recorded before his passing ..........it’s a great class but WHAT”

While smaller class sizes are good, schools make less money on them: massive lecture hall classes have the highest return on investment. This is because they only have facility maintenance and pay for one instructor (as well as a small cadre of assistants, but these are generally graduate students and upperclassmen, and as such are fairly cheap labor). The smaller, more intimate classes cost more to run, and are generally more enjoyable for everyone involved, but the labor costs grow. The best situation would, obviously, be much more like an apprenticeship than instruction – such a situation would allow for tests to be done away with and the mentor to tailor things to the apprentice’s aptitudes and interests. However, 1:1 costs far more than 1:18 or 1:200, and cost rules everything in this equation.

This means that the current situation leads to a temporary increase in the quality of education for some students, but it does so, essentially, by robbing the absent students (or convincing them to be party to their own robbery).

This brings us to the second issue that I want to focus on, going less particular, and this is the issue of bureaucratization. Bureaucracy is very important for an organization as large as a college. There’s the issue of managing and distributing resources, but as my experience in graduate school taught me, it’s important for the diffusion of blame from a concerted, solid thing into a generalized noxious vapor. It isn’t a matter of “I’m going to kick you out,” it’s a matter of “your funding wasn’t approved.” It puts the closing of possibility into the passive voice.

As per David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs, where he quotes from Benjamin Ginsberg’s book The Fall of the Faculty, which concerns the “administrative take-over of American universities”, backed up by a statistical analysis of colleges from 1985 to 2005, a time in which enrollment went up by 56%, but faculty employment only increased by 50% – while Administration ballooned by 85% and “staff” went up by 240%. These increases have been even more pronounced at private universities than public ones – over twice as extreme, on average. Graeber summarizes Ginsberg’s argument as being that, essentially,

since the eighties . . . university administrators have effectively staged a coup. They wrested control of the university from the faculty and oriented the institution itself toward entirely different purposes. It is now commonplace for major universities to put out “strategic vision documents” that barely mention scholarship or teaching but go on at length about “the student experience,” “research excellence” (getting grants), collaboration with business or government, and so forth.”

This was, according to Graeber, enabled by the rising power of Finance Capital in the 1980s, which has a habit of producing the titular “bullshit jobs” – which are meaningless, pay well, and produce a feeling of malaise in the people who hold them.

Of course, there’s the added issue that the increasing bureaucratization of the university has led to an increasing bureaucratization of all jobs within the University. It’s amazing how much time at the start and end of the semester is spent recording information into forms that are hosted on the same system as I’m getting the information from. Student attendance, final grades, reflective assessments of my growth and development as a teacher, my assessment of the real process made by students (which is somehow separate from the grades that I’m recording,) and a host of other bits of interpretation that need to be rendered into numbers.

Connected intimately with this is some information that I encountered in a Huffington Post article a friend sent me, “The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education” by Kevin Carey. While it wasn’t the principle object of the article, it did detail some of the economic forces at work here. The article itself is seeking to explain why the cost of online courses isn’t lower than in-person courses, a question that has been thrown into higher relief because of the COVID pandemic (the article itself is from April 2019).

The answer is, largely, that running online courses has become a sort of off-the-shelf program: corporations referred to as Online Program Managers (“OPMs”) run these programs and take up to 60% of the tuition payment, essentially branding the online courses as being from the school for a 40% fee. Notably, the costs of these online courses is much lower, but rarely is the savings passed on to the student (Georgia Tech’s College of Computing, which is nationally ranked at #8 in their field, made a masters degree available at cost for $6,600. A comparable degree from Columbia University, #13 in the field, costs $64,595).

This all is dependent upon the funding model that is in play for American Universities. They are funded, largely, through tuition, which is paid for by the government. Notably, Carey and his team of researchers found that:

Accreditors assess the administrative practices of schools, but they are indirectly funded by colleges themselves. And the biggest financier of higher learning, the federal government, can’t force a school to reduce tuition if it believes students are being overcharged. What all of this means is that colleges essentially approve one another to be eligible for government money.

Nor can students expect “the market” to help them figure it out. Universities aren’t like restaurants that rely on repeat customers: pretty much nobody gets two bachelor’s degrees. If you choose the wrong place, as many students do, it’s not easy to signal your dissatisfaction by transferring to a competitor. Besides, every year, colleges are practically guaranteed a fresh supply of high school graduates and adults looking for new skills. The result is a profiteer’s paradise: millions of highly motivated, naive, overwhelmed consumers loaded up with armfuls of government money.

According to this same article, OPMs only spend about $15 out of every $100 on instruction – the trick isn’t to provide a better product, it’s to create the image of a better product, a sense that the student is paying for something that is objectively better. As a result, there’s an arms race, and spending on actual better instruction is a losing proposition. Notably, $42 of every $100 is eaten up by profit for the OPM and University, and the remainder is taken up by administrative costs.

However, this money doesn’t come from nowhere – it becomes debt that weighs students down for life and cannot be discharged through bankruptcy. There is some discussion that some of this may be discharged by the federal government, but it should be noted that the man who made it impossible to discharge this debt through bankruptcy, Joe Biden, is the current president.

I think that over the past year something broke, and it wasn’t something widely acknowledged to be part of this system. What broke was trust in this system. Many people who had passed through it since 2000 had no or little faith in it, but notably we haven’t had the power to change it directly.

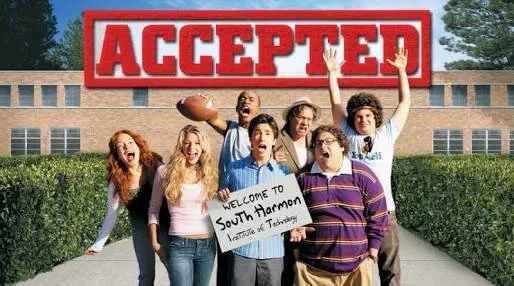

For a window into college, currently, I highly recommend watching — but preferably not buying — the 2006 Justin Long comedy movie Accepted. It’s pure propaganda.

The reason that this faith in the system of higher education has vanished is that those steering the system lost their faith in its mission before anyone else, during the aforementioned coup by the administration. Fundamentally, schools went from educational institutions supported through a sideline in finance to finance institutions with a sideline in education – and it is very accurate the finance capital is also called the FIRE (Finance, Insurance, and Real-Estate) sector, because it will spread like a wild fire if given the chance. Since the 1980s, the colleges and universities of the United States have done everything in their power to divest themselves of the actual mission of providing an education: they’ve precariatized their faculty, expanded their administration, focused on building Potemkin Villages of luxury (juice bars! Coffee shops! Climbing walls! E-sports!), and have now sold their very names to profiteers to make a passive income off of shoddy degrees in nothing, and the whole operation is shrouded in a mystique: you have to go to college. You have to go to college. You have to go to college.

But it’s not true.

Look, I really enjoy teaching. It’s the job I’ve had that most agrees with my temperament, and I love sharing what I’ve learned with other people. But I don’t think everyone has to go to college. Especially not when you’ll end up in debt for life as a result of it and it may or may not enrich that life.

I’m not even talking about employability here: I’m an English instructor, for god’s sake, and the perception is that this is unimportant. Even if you’re waiting tables, or minding a cash wrap, the things you learn may enrich your life, and lead to you having more interesting conversations. It could improve your life, though this is something hard to quantify.

But over the year of the pandemic, it’s certainly seemed less worthwhile to students, and the administration's insistence on steadily rising profits is exactly why that is. No one should pay full price for zoom university. I think everyone should be on board with this. My next point might see more dissent, but come with me on this for a moment: I don’t think any student should pay for college at all, not directly.

You can’t run everything like a business. Education and healthcare are exactly why you can’t. It creates destructive feedback loops that do nothing but generate misery and debt. Healthcare is a human right. Education is a human right. I don’t feel these are – or should be – controversial takes. When you make healthcare subject to the profit motive, fewer people are cured of diseases, because managed decline is more profitable. When you make education subject to the profit motive, you create conditions whereby more resources are placed in the part of the university that seeks to acquire this profit.

Inserting the profit motive into healthcare destroys health. Inserting the profit motive into education prevents education. We have all the information that we need to make this assertion, and we could end it at any time, because this is the product of human action. Unlike healthcare, we know what functional education looks like without the profit motive because we had something like it in the past. We could just do a more open version of what we did previously. It wouldn’t even take that much work.

All you have to do is close down the juice bar and re-balance the staff.

But, as with so many things, I don’t know if we will: the problem will persist so long as we love the causes more than we hate the effects.

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.)