A Spectrum of Haunting

This semester, I was given my first literature class to teach. I’m not sure I’m doing a good job – it’s a very different proposition from teaching composition. One of the things that was emphasized to me was to expect students to try to get around doing the work by using SparkNotes and similar resources. I’ve seen some of that – which is tragic, because these websites inevitably have absolutely terrible analysis. One of them claimed that the dominant religion of Japan during the period in which Matsuo Basho was writing his poetry was Confucianism – which seems inaccurate and vaguely racist, honestly.

But in planning this class, I tried to find things not generally covered by the traditional resources that are still vaguely canonical enough to get into in a literature class. I’ve made some missteps (I’m surprised by the coverage in these resources given to Juan Rulfo’s novella Pedro Páramo, which I first encountered in grad school, but which seems lightweight enough to cover in a class split between all four levels of undergraduate student), but perhaps the most unfamiliar to my students was the work of Stefan Grabiński, whose short story “The Motion Demon” I sadly had to give short shrift to. I put him in context next to Dostoevsky and Kafka, but he has more in common with H.P. Lovecraft and Edgar Allen Poe, despite his Eastern European heritage (he was ethnically polish, but born within the borders of what is now Ukraine.)

Rereading it in preparation for the class, I was struck by a simple but surprisingly deep question: what does it mean for something to be haunted? Not on the surface, but as part of a deeper cultural question.

Right now, one of the dominant subcultural genres is what is commonly called Analogue Horror. Or Analog Horror. I’m pretentious, so I tend to spell it with the “ue” at the end.

This genre snuck up on me a bit: I’m currently trying to get a group together to play through a campaign of Jason Cordova’s Public Access, and Edgar and I went to see the film Skinamarink earlier this year (indeed, they wrote a piece inspired by it that was quite good and connected to the idea of Hyperobjects), and one can point to the episode “The Outside” from Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities, which featured the delightful Kate Micucci as the lead character, led to use an evil skin care product by a bizarre late-night infomercial (this series, as well, inspired another piece by my writing partner, though in reference to a different episode – unrelated, but there’s something going on in a third episode, “The Viewing”, that I need to consider at some point, but that’s for another piece.) Yet further afield, I remember spending time back in my college days watching Marble Hornets on YouTube before I really started taking my studies more seriously.

What does it mean for something to be haunted? What does it make sense to think of as being haunted?

In Grabiński’s short story, the protagonist wakes from a daze to find himself on a train – he is often gripped by a maddening wanderlust that leads him to travel as far and as fast as he can. He is confronted by a conductor who appears to be some kind of servitor and extrusion for the railway itself, unbounded by normal laws of motion, and the two converse about the nature of absolute motion, and briefly touch upon relativity.

The story was written in the late 1910s, and trains had been present in that part of the world since the mid 19th century – in the 40-60 years since their introduction, thinking of the train as a site of haunting or accursedness became a coherent idea, and Grabiński was the man to articulate it.

It makes sense to think of such things as haunting – there is an eerieness to autonomous machines: motion and force without the obvious power of life behind it, making it move seemingly on its own. I can imagine it’s the same general unease that accompanies those Boston Dynamics videos of the dancing robots – the uncanny valley made to get up and dance. In the sense of analogue horror, though, it seems to be the fusion of two related but distinct phenomena: the ghostliness of the media that we consume.

I remember in my youth – the 90s, specifically – it wasn’t always possible to access the films you wanted to watch or the music you wanted to hear. Your best bet was to go to Blockbuster and hunt through the shelves, or spend time turning the dial on the radio. You could find music from the 50s and 60s on the oldies station, the 60s and 70s on classic rock, and everyone hated the 1980s. Television shows were completely out (the idea of a “boxed set” of a television show didn’t really seem to occur to people until the aughts. You had your memory, and that was it, and memory lied. The aura that surrounded this media was about the distance between your recollection and the artifact.

To a certain extent, this is part of what I was getting at with my piece on what I called the new dualism – instead of spirit being significant and matter being dumb weight that the ghost drags around, the totemic artifacts that we collect (vinyl records and books seem the most significant) is contrasted to the incomprehensible vapor of machine-readable data that we choke in. However, this still doesn’t answer our question, it just gives us a certain way of reading it: What can be haunted? What could be totemic?

David Herbert’s sculpture, monolith.

For most people, it seems that the answer is found in VHS cassettes. The miniature, home-portable monoliths, like something out of 2001, mostly dead by 2001. It may say what it is, or it may carry something uncanny curled up inside, like a mystery hiding at the bottom of a well (there is, in my read, a depth to these things.)

For me, though, and I’m not sure why, I’ve always gravitated to another artifact of the same era: the payphone. Part of this comes not from horror or fantasy fiction, but from cyberpunk – I’m reminded of the sequence in William Gibson’s Neuromancer where Case walks by a bank of payphones, and the closest one to him at any point in time starts ringing, so that as he walks, there is a wave of notification, as of something invisible and intangible reaching out to him. Another part comes from the memory of the bank of payphones at the local mall, each one set in a recessed nook of brushed, perforated stainless steel, and the way that they catch the light.

Pictured: an image I can feel in the bones behind my ears.

The telephone was a domestic machine, something that allowed you to reach out and speak to someone. The payphone was its anonymous public duplicate, and when the payphone rang, it could be anyone or anything.

For something to feel haunted, I think there has to be a sense of amputation. The ghost is the soul that’s been cut off from its flesh, the house is somehow cut off from the outside world, the payphone is the amputated voice whispering in your ear, the VHS tape is doubly amputated – the broadcast or recording stuck in the black box like the cutting of a plant stuck in a pot, and amputated from its history by its unknown provenance. Let’s extend this: it’s easy enough to imagine – indeed, to easily think of examples of – a haunted elevator or a haunted stairwell, so why does a haunted escalator feel like such a ridiculous proposition?

Think about it for a moment, this piece will still be here when you get back.

A haunted book makes sense; a haunted ebook reader feels a little silly, but could be handled right. A haunted car doesn’t need much explanation; a haunted bicycle could be done right, though I don’t think it ever has been. A haunted segway feels like an orphaned punchline. A payphone could be positioned as a gateway to a hadean underworld; a flip phone is out of date enough that it could be believed. A ghost-ridden smart phone feels kind of silly. We can accept that a television, film reel, or video cassette is haunted – hell, I think people would be willing to accept a haunted YouTube video. The idea of a cursed Netflix show feels like something from Stephen King’s slush pile.

This is tracing the outline of a concept.

Fisher’s final book.

For something to be haunted, it has to feel like it’s been abandoned – either in part or in whole. There must be an eerieness – a failure of presence or of absence. Something needs to be there when it shouldn’t be or not there when it shouldn’t be (I really have to find and re-read my copy of The Weird and the Eerie.) This is somewhat similar to William Gibson’s adage about always imagining new pieces of technology as old, collecting dust and forgotten on a shelf somewhere, wrapped in the cables that we’re all so eager to get rid of.

There also has to be a certain age to them. The cultural associations with the object in question has to have time to ferment into nostalgia. One thing that most theorists of nostalgia get wrong, though, is that it’s not about unalloyed love: to be nostalgic about something, you need to return to it (this is in the name – it means something like the “sickness of homecoming”) To return, you need to leave in the first place: you need to set aside childish things, thinking that it will make you more adult; you need to let your love curdle into disinterest or hatred and then scrape away the slick negativity that covers it up, finding something – not purified, necessarily, but congealed – underneath it. There’s kind of an Benjaminian aura to such things, in a weird, turned-around sort of way, invested not by the creator but by the audience.

Maybe for something to be haunted, you have to find yourself in the presence of someone else’s nostalgia, but they’re not there to experience it for you. With analogue horror, it’s often the sense that you’re in the presence of a dead person’s nostalgia, the ungrounded charge of their desired homecoming, unable to be released because they’re permanently absent.

The objects that make up our everyday, phenomenal world appear to us first at the center of our attention, and then gradually slip off to the periphery. At the very edge, they become emptied of our associations with them, with only a trace of the original emotional attachment to remain. The aura inverting and turning inward, fermenting until it becomes something strange: a haunting, a curse, a discontinuity in the sense of the world. What looked strange and new became normal, and as it ages and falls apart the strangeness returns redoubled.

I think that this question – what is it coherent to imagine as “haunted” – is an interesting one. There are certain things about our culture that are only legible to us through the medium of cognitive dissonance: if something feels like a joke, that means it stands at the twilit edge of what’s imaginable. If it feels like a joke, then it’s coherent enough to articulate, but doesn’t make enough sense to imagine completely.

Okay, let me pause and offer a probable criteria for what can be portrayed as haunted or cursed or otherwise supernaturally charged in list format:

First, for something to be open to this, it must have the sense of abandonment. I am tempted to draw a line between this and the Principle of the Magic Circle found in Huizinga’s theory of games, but I am resisting this. This isn’t just separation in space, this is an almost kairotic thing: when you interact with the object or place in question, it is as if the real world is on hold.

Second, extending this, there is the sense of time dislocation (if we wanted to coin something for this, we could call it “ectochronic”, but I’m going to save that for my even-more pretentious fiction.) For something to be haunted, we must imagine it as bridging the present moment with a lost one. This isn’t simply a matter of haunting, though, it’s deeply entwined with the aesthetic of the Gothic, which requires that horrific elements of the past return to menace and terrify the present. This also connects with the nostalgic: It must not simply be old and terrifying, but must be simultaneously attractive and repulsive, or at least give the sense that it could be both attractive and repulsive. To a certain extent the distance from the actual emotion is even better: it makes things feel complicated, and that complication easily flips over into obscurity, which is part of the next quality.

“Maybe the house just did that.” — me, after being asked to explain what happened in this book.

Third, there must be what I refer to as the sense of amputation. This is closely related to the quality that Mark Fisher refers to was the “eerie”, characterized as a failure of absence or a failure of presence. When you get down to this, it is about a normal order being reversed: something should not be there but is, or something should be there but is not. In my eyes, the most important word in these two statements is “should”. However, when I refer to “amputation”, I do not simply mean “eerieness” or similar – I mean that the quality we label “eerie” has a purposeful quality to it. A house is haunted because it should be occupied but is not and there is a reason for that, for example. However, this falls into a double eerieness, because the exact reason is likewise inaccessible and absent. Sometimes, as in the case of Stephen King’s 1408, Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, or (my initial reading of) Skinamarink, sometimes the haunting isn’t a lingering ghost of a person, sometimes it’s simply the physical world becoming imbued with agency and lashing out at human kind for no discernible reason.

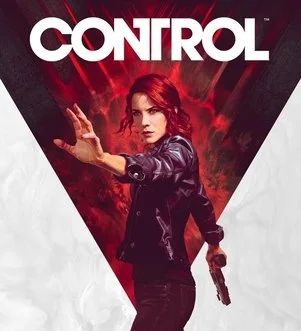

A reasonably good game, though I’m stuck on the room where you have to trap a monster in a side closet.

Finally, there must be an echo between the nature of the haunting and the original purpose. The haunted payphone allows you to speak to the dead; the haunted film reel allows the monster to enter your home, spectrally grown to ten times its normal size; the haunted animatronic is a fully autonomous being that has shed its false skin and is coming to take yours. If, on the other hand, the objects enable something that has nothing to do with their intended purpose, it flips over into the territory of the weird (an excess of presence in Fisher’s read) – take, for example, the comb from the 2006 miniseries The Lost Room, that allowed someone using it to stop time for a span of 10 seconds, or any of the artifacts from the 2019 video game Control – they go out of their way to explain why holding an eight-inch, late-70s vintage floppy disk allows telekinesis, but that has nothing to do with the function of the object itself.

I believe all of these, taken together, constitute an object that can be thought of as haunted, cursed, or otherwise “significant” in the context of a supernatural story. Likewise, I think this says something about how we construct historicity for ourselves. We are not haunted by good events, really, the ending of Beetlejuice aside (and, as much as I love that movie, having been a weird kid at the appropriate time, it has its problems), we are haunted by things that we want to forget. And this brings us to our real, easy definition of haunting: it is, when you get down to it, an inversion of forgetting. This, of course, brings us to the Gothic.

The Gothic and the haunted are deeply intertwined, and the reemergence of the Gothic genre as a major force points to a certain amount of material instability, as was noted on the most recent episode (on “Analog Horror” as they spell it) of the podcast Digital Folklore, and the general thesis of this – that we’re in a gothic revival due to heightening anxieties – rings true for me.

What I must wonder about, though, is another question, simple to ask but hard to answer: what happens to our haunted signifiers if nothing slips away? Turn on the radio and spin the dial a bit – you’ll find a station claiming to play the best of the “80s, 90s, and today!” where “today” is longer than the other two periods put together. I’m neither the first nor will I be the last to think about this. Barring some strange new legal regime or catastrophe of digital infrastructure, everything that ever was will be at your fingertips forever. It will all be “today” until it’s gone forever.

And now I’m just thinking about Serena Williams’s Glass Onion cameo.

Nothing will ever be new, but neither will anything ever be old. Can you tell your children a story about a haunted tablet? Will we see a new version of the story about the red slippers – the ones that force a ballerina to dance herself to death – about a cursed Peloton bike? Can an always-on-whatsit-as-as-service be the site of something weird?

For sixty years or so, the favorite pastime of American families was staring into the warm and comforting glow of a magic lantern powered by a particle accelerator – now, we’ve replaced it with flat screen televisions. This isn’t a RETVRN thing – I have no particular attachment to the way things were (for all I write on nostalgia, I often feel weird and sad when I succumb to it, and often remember things having been better, as I’ve documented.) However, I miss the New. I miss the sense that the future would be different.

So maybe that’s the real future of the gothic: The Hauntological Gothic, nostalgic for stillborn futures that have been amputated to spiral off into the eigenspace of conception.

Which just brings this song to mind for me. Perhaps the whole album is the kind of hauntological gothic thing I suggest here at the end?

※

If you enjoyed reading this, consider following our writing staff on Twitter, where you can find Cameron and Edgar. Just in case you didn’t know, we also have a Facebook fan page, which you can follow if you’d like regular updates and a bookshop where you can buy the books we review and reference (while supporting both us and a coalition of local bookshops all over the United States.) We are also restarting our Tumblr, which you can follow here.

Also, Edgar is being included in an upcoming anthology — read our announcement here.